Edie (13 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

Suddenly my father broke out in Mercedes sports cars and he got a big Mercedes sedan for my mother. A foreign car was a big step in those days; it was ostentatious. My father gave my mother a solitaire diamond and a mink coat. Something had really happened. I think a certain resignation set in on my father’s part, and he abandoned puritanical attitudes that they had shared before.

Another big change was that the three little girls moved into the main house. They had had their own house with their nurse, Addie, most of their lives, but now Edie and Suky and Addie moved right next to my parents’ room, and Kate lived at the other end, near the kitchen. Later Kate moved in with Pamela in the girls’ bunkhouse, which had been brought over from the old ranch. I seldom came home, but when I did I was struck by how close and jolly the rest of the family seemed. Bobby and Pamela always had friends staying and there was lots of joking and teasing. I noticed that my mother had suddenly drawn Edie and Suky very close to her. They were like little stamping, whinnying ponies; at meals they sat on either side of her and held her hands tightly while they ate.

My parents’ daily ritual was stI’ll the same as at Corral de Quati. They came to breakfast, my mother dressed in English riding clothes, and my father in a T-shirt and jeans of some sort—usually very light tan, though he wore frontier pants a lot in the early stages. He always had a bandanna handkerchief in his rear pocket, sticking out.

After breakfast Fuzzy did his exercises out by the pool in this little loincloth he wore. It wasn’t a real jockstrap, but a neat little thing which looked more like a cotton bikini. He also did his writing there, sitting in the sun in this cotton bikini with a great big sombrero on his head. He was always nearly naked. He had this belief that the human body revealed the discipline and the performance of the person inside. With his enormous thorax and the muscles of his arms and chest and abdomen, and his priapic, almost strutting bearing, the main effect was one of fantastic vitality.

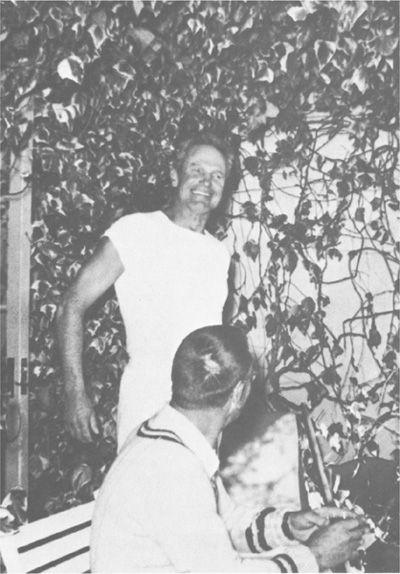

Sunday lunch, Francis Sedwick with a guest

After lunch my parents would always rest until three o’clock and then we would meet at the barn to go riding. At dinner my mother would wear a Chinese mandarin coat, exquisitely embroidered, and satin pajamas. My father usually wore a gabardine suit and a bow tie. He always had the same haircut, a long crew cut, sort of stuck up: a brush cut, I believe it’s called. My mother cut it for him. He was very vain about his hair, very pleased that he was not balding . . . everything to do with veer-il-i-ty! Well, he

was

something. When he came to the Katharine Branson School to see me, the girls stood at the windows and stared at him. He was so beautiful. “Swoon! swoon! faint ! faint!”

Laguna was also different from Corral de Quati because life was as jolly as it had been at Goleta. It was raffish and violent, but it was very jolly. How funny my father was! He was hilarious. And he had enormous charm. He was a real Don Giovanni.

My father had the feeling that, if he survived, it was by an act of will. He had Don Giovanni’s defiant attitude toward fate and consequences. In that sense he was heroic. He had the physical beauty of Don Giovanni, the seductiveness, the taunting quality of Don Giovanni, the

disprezzo

of Don Giovanni. Life was a feast for him and he really was going to drink its cup to the dregs. He bore himself as if all eyes were upon him and he was center stage all the time . . . which he was. He moved in the world and you felt him.

RICHARD PARKER

Duke Sedgwick’s sculpture was like him—it had a kind of courage. Great huge statues of horses and generals and God knows what. Very conventional, very academic. But you felt he had no inhibitions, no lack of self-confidence about what he was doing. I don’t know why he became a sculptor. It seemed a strange profession for him to indulge in, but he liked studios, I guess.

JONATHAN SEDGWICK

He looked tall, though he wasn’t very tall at all. He was only five-eleven. It’s your bearing. If you have your energy together, you can be gigantic. He always rode up above everyone else along the side of a hill. But even if he happened to be riding

below the others, he stI’ll looked bigger. The energy was heavy. My father was a peat blaster of energy.

RICHARD RAND

Every year the Sedgwicks had a round-up. Marvelous occasion. Hundreds of people would come, and many of the men would go out with Duke Sedgwick to round up the cattle and bring them in. Real western scene, right? Lots of children and a great deal of activity. Every person you knew would sit along the fence and watch them rope the calves and tie them down and brand them and all the rest.

After the round-up you had an enormous outside picnic, with picnic tables, and animals turning on spits—something out of an old painting. Everybody got cozy and sat at the tables with the working people. Duke went around with a quart of whiskey, which he would hold up to each of the men there, who would ceremoniously—a sort of nice Faulknerian touch—take a swig and pass it on.

The new gentry out there were from New York and Boston. They came to Santa Barbara for various reasons, usually because they had become discontented with life in the East and its pressures. But in a sense it was a very Eastern scene—a certain cultural snobbishness, the feeling that if you came from the East you were more civilized than the yokels who grew up there. We wore Brooks Brothers clothing rather than sports shirts. We socialized with each other.

So the social stratifying was fierce. If you came from the Middle West, you had damn better come from a meat-packing fortune, or forget it. If you didn’t, you had all the bad vibes and no redeeming features. The social lines were very tight. Of course, it was also promiscuous. You were allowed to sleep with just about anyone.

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

At one of my parents’ parties I saw my father disappear into the bushes, right in front of my mother, with his arm around a woman—just traipsed off into the bushes in front of fifty people. I was horrified, but my mother never turned a hair. Our French cook, who adored my mother, once surprised my father kissing another woman just as my mother came in. My mother said to her in French, “That’s nothing, Monsieur is just teasing, that’s nothing.”

JONATHAN SEDGWICK

She didn’t take her frustration and anger at my father’s affairs out on the children. She’d get allergies and needed special diets. She’d stay in bed a lot with what were said to be low-grade fevers,” and she began going to the hospital. Then my

father would get scared because he’d think he was going to lose the one who really loved him. My mother finally got to the point where she wouldn’t go anywhere. They’d be invited to a dinner party and at the last minute she’d pretend to be sick, or have some other great excuse at the last minute for why she couldn’t go.

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

My mother was the shyest person. She liked to hide unless she was in control. She was terrified to walk in alone anywhere. The only place she’d feel comfortable away from home was in a club. She wouldn’t dance at a party; she felt that over the age of twenty-five it was not dignified to dance. My father agreed with her that it was not dignified for her to dance.

My mother didn’t have the glamor and lightheartedness that Fuzzy saw in other women, but she was a real lady, and she knew that she had what he needed—namely, utter steadfastness. And money. He couldn’t have done without either. He would tell me how bad I was and then he would

always

say: “Now your mother, she’s a good person.” Yet in some way she wasn’t enough for him any more. So she became a kind of Mediterranean mother who maintained the family and the hearth. He went out and had flings, but he always came back.

SOKY SEDGWICK

Maybe Mummy had all of those children because Fuzzy wanted to have a little tribe to show everybody. We were paraded around a bit, just to show the guests the children, that’s what it was. I didn’t know why I hated it so much. I had to play the piano for them. I was Miss Mozart. Edie was Miss Rembrandt. Minty was Mr. Leonardo. Christ, we were all supposed to be God knows what—geniuses to add to Fuzzy’s pyramid.

SUSAN WILKINS

My God, the father was something! A cross between Mr. America and General Patton. We were all whinnying little girls in the Fifties, we didn’t know anything. After all, we were privileged Wasps who had come out of the mold of private schools. We all had the same basic attitude toward life: we all wanted to be popular with nice college boys, marry a handsome man from Harvard, Yale, or Princeton, have a few babies, wear cashmere sweaters and tweed skirts in the autumn, play a good game of tennis, join the country club, and never be a force for anything.

I spent a week at Rancho Laguna in August, 1954—one of the most extraordinary and shocking times I have ever spent. I went there to be

a bridesmaid for Pamela Sedgwick’s wedding to Jerry Dwight. Pamela was a tense person who bit her fingernails, a rather shy, slightly horsy-faced girl with brown hair and a rather angular face, which her brother Bobby also had.

We arrived and were immediately ushered into the presence of this “man,” this father with his exaggerated views about human beauty. Nobody who wasn’t beautiful was allowed around. He began by making comments about each of the bridesmaids, the length of our legs, the size of our bosoms. There were two of us he took a particular liking to—Ginny Backus, who was a knockout, and Shelley Dwight, who was Jerry’s sister and had that Irish red hair that caught the sun. So while much of that week was spent in tennis and swimming, which should have been fun, all the time you were being made to wonder whether you measured up or not—whether you cut the mustard. It certainly helped if you were beautiful and rich.

There were a lot of tears that week, a lot of us in our rooms crying—bridesmaids, the bride.

Lots

of tension. I remember it as being physically exhausting. We went from dawn to dusk. The tension was phenomenal.

Phenomenon

There was something almost mythological about what was happening. Duke Sedgwick reminded me of somebody from Mount Olympus. I’m thinking of Titian’s

Rape of Europa

in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

That

was the feeling. It was a stud farm, that house, with this great stallion parading around in as little as he could. We were the mares. But it wasn’t sex. It was breeding . . . and there’s a difference, of course. The air was filled with an aura of procreation. Not carnal lust, but just breeding in the sense of not only re-creating life but a certain kind of life, a certain elite, a superior race. There was no romance. It was stultifying. I remember Jerry Dwight saying, “I’ve just got to get Pamela the hell out of here.” I never heard Pamela disloyal to her mother or her father, but I think she wanted to escape. Marriage was the way out for her.

The other aura that seemed to permeate everything was the element of brutality. Great violence! Bobby had his accident when I was there—he fell off a bicycle going down a steep hI’ll and broke his neck. He held on to his head when he got up, which was all that kept his spine from severing. The family was in pandemonium because for a while they didn’t know whether he’d walk again, or even live. The father was on very bad terms with Bobby, and there was a whole ruckus about whether he would even go to the hospital to see him—a lot of yelling behind closed doors. A lot of crying. The mother was stunned. Everybody was shocked.

SACCIE SEDGWICK

Traction didn’t work, and Bobby’s neck had to be fused. It was a very dangerous operation. Bobby had a dream in which he crawled on his knees down the long corridor to my parents’ bedroom at Goleta and begged them, “Please give me another chance,

please,”

and they told him, “No, you have had your last chance.” When he came out of the hospital, he was in a cage, this huge apparatus, with his hands on the bars and his dark eyes staring out.

SUSAN WILKINS

We learned that Bobby would be able to walk again, and so that problem was forgotten. It was back to business. Duke appeared for the dress rehearsal with his shirt open to the navel. Afterwards we went swimming. I remember this great red hot sun sinking over the pool, and while we were standing around—some of us were already in the water—he came strutting out in a little blue bikini like a peacock, showing us with his arms spread out how he could ripple his muscles back and forth.

I can remember Edie at this poolside episode, the father flirting and Edie being angry about it. She stalked off. She was wearing very short shorts, those long legs, and a man’s white shirt, a very thin girl with brown cropped hair, and she said something like “Oh, for God’s sake, Fuzzy!” How old could she have been? Eleven or twelve. She was young and she was disgusted. She was so live then; she glided—I can see how she moved—so thin, and suddenly she zipped off, just

phftt,

like that.