Edie (5 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

Susanna Shaw Mintrn, Murray Bay, Canada

Three of her children died within four years. The terrible tragedy of Granny Minturn’s life was the death of her fourth child, Francis, who died of diphtheria at the age of six. She wrote about him in a book she had privately printed afterwards. The doctors had asked permission to perform a tracheotomy.

His father and I said we were willing; and they took our darling, laid him on a table, and lit gas-lights and candles all about him. He looked like a beautiful marble image as he lay there. Four doctors held him; they wanted us to leave the room, but we could not. As soon as the incision was made, he whispered in a frightened, hurried way: “Mamma, mamma, mamma, mamma!” And I ran to him and taking his dear hand, I said, “Frankie, darling, mamma is here, she wI’ll not leave you.” Then he said to the doctors, “Please don’t, please don’t.” Those were the last words we ever heard him say, for after this operation the voice was gone. . . .

MINTURN SEDGWICK

My brother Francis, Edie’s father, was named after that Francis Minturn. There were four of us. The eldest was Henry Dwight Sedgwick, Jr., whom we called Halla. I was the second. Then my mother had a daughter, Edith, who only lived for a half a day or a day. I can remember picking flowers for her grave in the rain. Then two and a half years later came Francis. He was the last.

Francis was a very delicate child. They said he was born with an umbilical hernia, which is a hole in the abdominal muscles, but he screamed so much I have since thought the strain of his yelling was perhaps what caused the hernia. I remember as a baby he always had a big piece of adhesive tape covering his tummy with a little hole in it for his belly button, sort of pulling him together. My mother told me years later that when Francis was about two, he wanted to stand up and run around, but he didn’t have the strength. He’d just collapse. My mother could see that Francis was sort of fading away and she was terribly concerned. Then Halla developed pneumonia for the second time so our father, Babbo, decided for the sake of the whole family to go to a warm climate; he chose Santa Barbara in California.

My parents rented a small house up in Mission Canyon with the Sierra Mountains behind them and the Pacific Ocean in front. The house had a Utile decklike veranda covered with morning glories. My father’s letters from that time express the kind of reservations about California one might expect of a New Englander on his first visit to the Coast. He said he felt he was in exile. One of his letters complained that California lacked the marks of man’s labor; it needed ruins and castles.

John Singer Sargent’s portrait of Edith Minturn Stokes (for whom Edie was named) and her husband, Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes

My parents brought along an Irish maid and a trained nurse for Francis called Miss Thompson, who told the maid, “I’m going to stay here until the little fellow is put in his grave.” It was true that Francis seemed to be losing ground, and I think my mother should get credit for bringing him through, because she made up her mind that he was going to get well. She dismissed the first nurse and asked a remarkable Christian Scientist nurse to come out.

She

made all the difference. She was gay and always sang to Francis. The whole atmosphere changed, and he survived.

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

My grandmother May must have been magnificent when she was young: large and dark, with an austere kind of beauty. But she could be fierce. Uncle Minturn told me she once hit Halla in the face with the bristle side of her hairbrush. He said she was terribly embarrassed because when the family gathered at Grandmother Minturn’s for Sunday lunch, there was this little boy with angry marks on his face. And I know she was severe with my father. Having already lost her infant daughter, Edith, she must have focused an enormous amount of anxiety and rage on him. She hit him, and he was scared to death of her. In photographs he has a sad but gallant look on his face . . . poor little man. He never said a word against her and spoke of her as if she were a saint. She

willed

him to survive. As for Babbo, he read stories to his sons and did plays and charades with them, but he cannot have been a strong figure as a father. He told me once that he tried to intercede for my father, but, as he said, “I never had any influence with her.” My grandmother was the dominant force in the family.

HELEN STOKES MERRILL

It irritated May Sedgwick that Francis wasn’t strong. She felt that he must take hold of himself and rise above it. She was anxious for him to outgrow his weaknesses and his delicacy. Auntie May was quite fierce. She wanted to teach Francis what “hot” was, so she put his finger in the candle flame and said, “Now, that’s hot, that’s bad. You mustn’t get burned.”

She had a great many theories about bringing up children. Minturn told me years later that he was brought by his mother to see me in the tub when I was about three so that he’d know what little girls looked like. They had no girls in their family—they had lost their daughter, Edith, who only lived for a day—so Auntie May thought it was important for the boys to know how girls were put together.

Francis Minturn Sedgwick (Edie’s father)

Francis Minturn (1871-1878)

Francis with his uncle, Robert Minturn

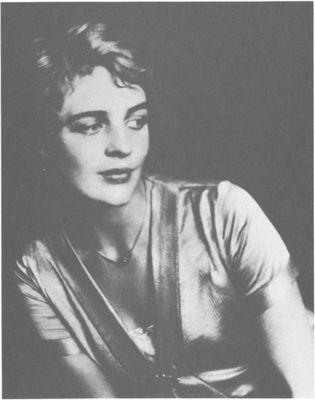

Rosamond Pinchot

The Sedgwicks used to come and stay, always a jump behind us as we moved from one house to a larger one on our Greenwich estate. My father—he was a recognized young architect and the author of the

Iconography of Manhattan Island

—had bought a Tudor mansion he’d seen in an advertisement and brought it over from Ipswich, England, in wooden crates. Next to the mansion he built a walled garden—it was a little kingdom, all protected—which was called the Pleasaunce. It was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, the architect of New York’s Central Park.

I remember Francis’ mother with her feet up a lot, lying on a chaise longue in the little cottage on the estate which she and Babbo rented from my parents. She seemed withdrawn and concerned about her health.

At that time Francis—he was about nine—was very tense, always on the move, just a little dynamo with dancing brown eyes. We were always on a very competitive basis. He lived a life of fantasy in which I, his devoted follower, would do whatever he dreamed up. Once he told me to jump off the wall of the Pleasaunce. It was about six feet high, and he said, “Go first!” I jumped off, and for a couple of days I could hardly walk. He just slid down the wall when he saw how low I had been laid.

We fought wars against the neighborhood children. Indoors he had enormous sets of toy soldiers. He had whole battle plans. He was always planning wars. His brothers began calling him the General, and I think he liked that nickname. He wanted to grow up and be a general. He played the commanding officer on both sides of his war games—a type of military solitaire.

I was Francis’ closest friend, and Rosamond Pinchot, another cousin of ours, often played with us. She was very tempestuous, Rosamond was. In fact, in later years Francis worried that his daughter Edie might turn out like her. Rosamond once took a carving knife to her older brother, Gifford. I actually saw it happen. The two had an argument of some sort at lunch, and she just grabbed up the knife and went for Gifford until her mother, Aunt Gertrude, intervened. Rosamond was a lovely-looking child—great blue eyes, shining blond hair, and a very full mouth. She grew up to be quite a beauty. On an ocean crossing with her mother in the mid-Twenties, Max Reinhardt, the theatrical producer, became infatuated with her and offered her the

role of the nun in

The Miracle

. Lady Diana Manners was the Virgin. Anyway, Aunt Gertrude accepted, or let Rosamond accept. And it was her debutante year, too. The part was nothing, no acting involved at

all

. Rosamond was just required to

run

(I think she was escaping from a nunnery) up one aisle of the theater, around the back, and down the other, in her habit and with her hair flying. Everybody was just fascinated. The play had a tremendous success—it ran for three hundred performances or so on Broadway—and all of it went to Rosamond’s head. She went into something else, and she was a total flop: she couldn’t act at all.

She committed suicide finally, years later. She asphyxiated herself in the front seat of her car in the closed garage on a rented estate. Mother’s chauffeur told me that just before, she had gone back to our house in Greenwich, where she spent a long time sitting in the Pleasaunce. I can understand why. It was an island for all of us—a serene, secure place. But it was all torn down after the Second World War. When Francis went to boarding school, we drifted apart. I felt hurt at first, because we’d done everything together.