Edie (30 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

One day my mother was visiting from Connecticut. She was sort of an alcoholic. Somehow or other my mother spoke to him out there on the street and she invited him upstairs to the apartment. I walked in later, and he was sitting there. He looked then exactly the way he looks now. He hasn’t changed an iota I He had been having this conversation with my mother, who was a bit looped. So I sat down and talked to him. He told me all about himself and how he lived someplace with his mother and twenty-five cats. He seemed one of those hopeless people that you just know

nothing’s

ever going to happen to.

Just a hopeless, born loser. Anyway, it was friendly and pleasant, and then he left.

He started calling me every day after that. He’d tell me what was happening to him, and his troubles, and about his mother and all those cats, and what he was doing. I didn’t want to be un-nice or anything, so I sort of put up with it. Then one day when he called up my mother, she told him not to call any more. She was drunk at the time. Like all alcoholics, she had Jekyll-and-Hyde qualities, and although she was a basically sympathetic person and thought he was very sweet, she lit into him. So suddenly he stopped writing or calling me.

I didn’t hear from him or about him until suddenly one day D. D. Ryan bought a gold shoe Andy had dedicated to me in a show and sent it to me as a Christmas present. She told me, “Oh, he’s becoming very well known, very on-coming.” Even then I never had the idea he wanted to be a painter or an artist. I thought he was one of those people who are “interested in the arts.” As far as I knew, he was a window decorator . . . let’s say, a window-decorator type.

Then I ran into him on the street. When I had known him in his previous incarnation, he seemed to me the loneliest, most friendless person I’d ever seen in my life. He was surrounded by seven or eight people, a real little entourage around this person I had really thought quite pitiable.

Then he started sending me pictures again, including a portrait of me that if you look at you can tell I didn’t sit for him.

I think, looking back, that at a very early age he had decided what it was he wanted: fame—that is, to be a famous person. His drive was simply that: fame was the name of the game . . . not really talent. Not art. Whereas with me I think it was the other way around: an intense preoccupation with an art form, which in turn led to fame. Mind you, I’m not saying that Andy Warhol doesn’t have any talent, because obviously he has

some;

he has to. But I can’t put my finger on exactly

what

it is that he’s talented at, except that he’s a genius as a self-publicist.

DAVID BOURDON

Despite his growing success Andy was intimidated by the art-world people, especially the Abstract Expressionist group that hung out in the Cedar Bar. That generation of artists had struggled for so long for the little amount of recognition they got, only to be eclipsed by Pop Art, that they had this tremendous amount of animosity, especially toward Andy. That a shoe illustrator should be given

a show at the Stable Gallery rubbed a lot of artists the wrong way. Andy was very wary of those people.

WALTER HOPPS

The Abstract Expressionists took the stance of workingmen—Franz Kline packing a lunchpail and marching to the other end of his studio. This sort of blue-collar approach was carried on from BI’ll de Kooning to Larry Rivers and Mike Goldberg. That’s what the Cedar Bar in the Village was all about . . . no chic, no chichi, no frills, no nothin’! It was bright with a kind of yellowish light, dirty, and it was for serious drinking, talking, and arguing.

By the end of 1962 Pop Art was exploding in the American consciousness. The movement happened overnight, and Andy was very much included. That spring

Time

magazine took the lid off of it for the mass media with an article called “The Slice-of-Cake School,” generally decrying and instantly making controversial this new manifestation. Andy had his first show of the Campbell Soup cans out in the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles.

I remember how really insane the opening was at the Sidney Janis Gallery in New York in November, 1962, for a show called The New Realists” that combined all these

new

American Pop people—Warhol, Rosenquist, Segal, Lichtenstein, Tom Wessehnan, and others, along with European supposedly Pop people, the first time they had all been seen together in New York. Jean Tinguely’s work—you know, the artist from France who makes the mad machines—sort of set the tone of hysteria. He had an icebox that had been stolen from an alley outside Marcel Duchamp’s secret studio, and when you opened it, a very noisy siren went off and red lights flashed. This icebox really had nothing to do with Pop Art, but it set the noise and tone that was to continue all the way through the Sixties.

GEORGE SEGAL

Sometime in 1963, for some peculiar reason I could never understand, Salvador Dali and I were both invited to a mid-morning housewives’ TV program to discuss Pop Art. Everyone in the magazines thought it was fun-and-games—a mockery and celebration of American vulgarity. I didn’t think so, and Dali, to my amazement, came out with this long gobbledygook that Pop Art was really an obsession with death and nihilism. I found myself absolutely agreeing with him. Jasper Johns had just done

Tennyson

and

No

—paintings that were dull, dense negations, pulling shades down.

No,

you can’t see me;

no,

you said no to me;

no,

I don’t want to get old;

no,

I don’t want to die. This is what his paintings were saying to me—nothing to

do with entertainment, fun-and-games, or the celebration of vulgarity. Warhol’s early images of Jackie Kennedy, Elvis Presley, electric chairs, those car crashes—everything was done in pastel colors, thin, bright, scintillating, but since they were about the most dense, horrifying feelings, they made a shatteringly effective statement. And Marilyn Monroe—a double obsession with style, beauty on the same extraordinary level to be admired with death and negation. A shocking juxtaposition, and I think effective.

JASPER JOHNS

I liked Andy’s Brillo boxes—the dumbness of the relationship of the thought to technology—to have someone make those dumb plywood boxes and then paint them. I mean, artists have had other people make things for them, but nothing quite so simple-minded. Yet those boxes must have involved a lot of thought and decisions on his part—how they were going to be made, and certainly the colors. I have one of the first ones, which is a different color than the ones he finally came up with. He came to see me once in the early Sixties when I lived on Riverside Drive and brought me a present. It was a sculpture of a Heinz Tomato Ketchup carton. Then a while later he said that the one he’d given me wasn’t right; he would like it back so he could give me one that

was

right. I didn’t return it.

LEO CASTELLI

Jasper made a tremendous impression on Andy. He really understood how good Jasper’s drawings were and, even more important, the impact that Jasper’s

mind

had on him—the use of the flag, the numbers . . . one of the great basic events at the end of the Fifties that influenced everybody.

JASPER JOHNS

When I was growing up, I knew I wanted to be an artist. It meant being an interesting person who was doing interesting things to which people paid attention, and not being who I was at that time—someone living in a little town in South Carolina. I knew that you didn’t do it there. I was anxious to get to New York, and I came on the Silver Meteor, the fastest train going. But I did not leave and forget where I had been. I never did anything terribly dramatic; I didn’t run away; I didn’t dismiss the past. Is it important for an artist always to keep a connection? I think so.

You asked me if we need more than one Warhol in this century. Well, I guess if we need them, we wI’ll make them. Haven’t got much time left, though, in this century—just about enough to make a young one.

DANNY FIELDS

By the end of 1963, Andy moved into a loft on a floor of a factory building on East Forty-seventh Street—I think they made hats there. He didn’t dub the studio The Factory,” like a christening; it was just what people started calling it. What I most remember about the Factory itself is the aluminum foil that covered the walls, and the stuffed couch. Stone floors, a lot of paintings, a lot of standing around, a movie projector and cans of film. Some Salvation Army furniture to sit on. When the Velvet Underground was there, they had rock-band amplifiers, drums, and stuff. A coin wall telephone by the door; it was extremely important: there’d always be a line of desperate people, calling in or out. The Factory was totally open; anybody could walk in. At one point they put up a sign,

DO NOT ENTER UNLESS YOU ARE EXPECTED,

which everyone ignored. There was always an ebb and flow of people . . . like a crowd on a street corner or Sheridan Square.

WALTER HOPPS

There was always a shortage of places to sit. There was that decadent overstuffed sofa on which a lot of the sex play of the movies was shot, but that quickly filled up: people lying on it, lounging, and so forth. I think there were a couple of director’s chairs, maybe more. Andy never sat down. One always had the sense of him standing, or pacing around slowly. This was Andy the sleepwalker in the mid-Sixties, on his feet all the time.

Everyone around him was ravaged on drugs, though I never saw Andy smoke a joint. One night I was at the Factory at a screening of some of Andy’s films. Cecil Beaton was there with his friends, filling up whatever comfortable places there were to sit, apart from that damn couch. The floor was filthy in that place, and the movie was pretty long and boring. In the gloom I saw what looked like a rolled-up carpet and I went over and sat down on it. I sat there for a while until Andy came slowly over and said, “Uh, uh, I guess he’s so out of it, it doesn’t matter, but that’s . . .” and he mentioned a name. I was sitting on some guy who was lying on the floor as straight and symmetrical as a rolled-up rug—his jacket so tucked up about him that I had mistaken him for a carpet! I mean, this guy was really wiped out.

HENRY GELDZAHLER

A clubhouse. It became a sort of glamorous clubhouse with everyone trying to attract Andy’s attention. Andy’s very royal. It was like Louis XV getting up in the morning. The big question was whom Andy would notice. There are artistic personalities who need enormous amounts of people around them where they’re working—Hockney, Rauschenberg, Warhol—I imagine like Peter Paul Rubens, who always had bunches of people around. Andy can’t be alone.

I first met Andy when he came to the Metropolitan Museum, where I was a curator, and in the next six years we saw each other just about every day. It was magic: we knew that we were on the same wavelength. He immediately knew that I knew things that he could use . . . “smart stuff,” he called it. He used to say, “Oh, you know so much. Teach me a fact every day and then I’ll be as smart as you are.” So I said, “Cairo is the capital of Egypt.” He said, “Cairo is the capital of Egypt.”

My favorite was a telephone call at one-thirty in the morning. “Henry, I have to talk to you.” I said, “Andy, it’s one-thirty in the morning.” “We have to talk,” he said. “Meet me at the Brasserie.” I asked, ‘Is it really important?” He said, “Yes, it’s really important.” So I said okay; I got dressed, took a taxi, and met him at the Brasserie. We sat down at a table. “What is it?” I asked. “I have to talk to you. I have to talk to you.” “Yes? Yes?” “Well,” Andy finally said, “say something.” That was it—a cry for help of some kind. Sometimes he would say that he was scared of dying if he went to sleep. So he’d lie in bed and listen to his heart beat. And finally he’d call me. But it was amusing, too, in its mad way. He did like to hear me talk. Sometime that year he was asked to do a radio interview at WBAI and he asked, “Can I bring a friend along?” So I joined him at the microphone. They would ask a question and he wouldn’t say anything. So I’d lean forward and say, “What Andy means is . . .” and I’d answer it. Once in a while he’d say yes when the answer was no. Then I’d say, “When Andy says no he means yes,” and then explain. At the end, the interviewer said, “I’d like to thank Mr. Geldzahler from the Metropolitan Museum for being with us today, and Mr. Andy Warhol.” Andy grabbed the microphone. It was the first time he spoke in the whole interview. He said: “Miss Andy Warhol.”

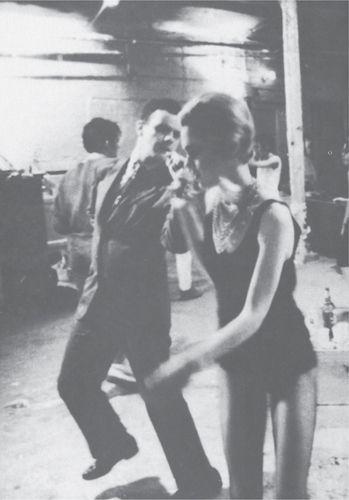

Edie dancing at the Factory with Donald Lyons