Edie (35 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

I tried to grab his cock, I mean through his pants, of course, just to watch it shrink. Or touch him on the shoulder. Anything. Any touch was like a burning poker. It just got to be a joke. You could even reach your hand out and pull it back the way you would from a hot iron, and not even touch him, and he’d shrink. That was the conditioned reflex.

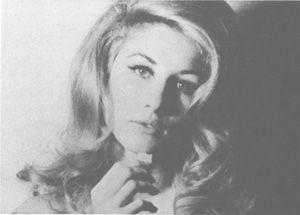

Baby Jane Holzer in

13 Most Beautiful Women,

1964

Viva

ISABEL EBERSTADT

I had the impression that Andy’s relationships were not overtly physical. He always said that he “couldn’t bear to be crunched again.” He’d had some unhappy relationship in his younger days and had decided to withdraw himself emotionally as much as possible. So he worked out this curious formula where he lived as a voyeur.

I was moving out when Edie was moving in. Andy was as taken with her as I think it was possible for him to be with a woman. Edie spoke to me a little about the world she’d left in order to be with Andy: she claimed her father had forced her and her sister to sit in a sphinxlike position with bared breasts on the top of columns flanking the entrance to the driveway when guests came to their place in California. Edie’s story was that her father would beat them brutally if they moved. A lot of what she used to tell me turned out to be true. I really became confused about how much was true and how much was fantasy.

JANE HOLZER

It was getting very scary at the Factory. There were too many crazy people around who were stoned and using too many drugs. They had some laughing gas that everybody was sniffing. The whole thing freaked me out, and I figured it was becoming too faggy and sick and druggy. I couldn’t take it. Edie had arrived, but she was very happy to put up with that sort of ambience.

DANNY FIELDS

Edie fit wonderfully into all this. What was great about her was that she was attracted to the most brilliant and crazy people—Ondine, Chuck, and Andy. She was really a poet’s lady. Most of these people were probably gay, but they were seriously in love with her. She was very beautiful, which anyone can respond to. And she made them feel like men. She would come on helpless, which brought out their strengths.

ONDINE

One night after we had just made a film Edie and I walked into the film co-op on Forty-fifth Street—the Mekas thing. Jonas Mekas, the underground filmmaker, was sitting at a table, and he

fell

off the seat when he saw us and scalded himself with hot coffee. He couldn’t take the idea that this whole stardom thing—Edie, this poor little rich girl, and I, this vicious street thing—were actually

happening in

his

world,

his

realm. It must have been a very glamorous moment because we both looked so beautiful, and he just was knocked off his seat.

HENRY GELDZAHLER

Andy always picks people because they have an amazing sort of essential flame, and he brings it out for the purposes of his films. He never takes anybody who has nothing and makes them into something. What he did was recognize that Edie was this amazing creature, and he was able to make her more Edie so that when he got it on camera it would be made available to everybody.

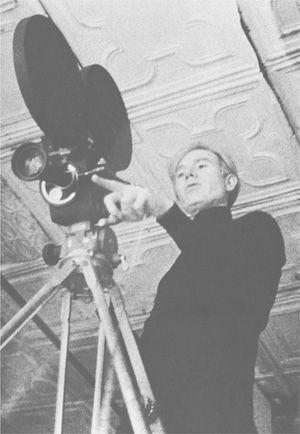

GERARD MALANGA

Andy never actually directed a film. He was a sort of a catalyst genius who would get people to do things for him in front of the camera. But he never went for anything like rehearsals. All he did was turn on the camera button and turn it off. Andy had it in his head that it was like magic. He wanted everything to be Easyville. He thought of himself as Walt Disney, you know: just put your name on something and it wI’ll turn into gold . . . some kind of alchemy.

RONALD TAVEL

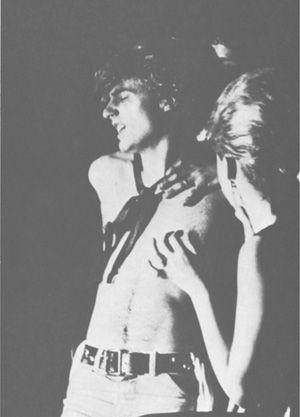

Vinyl

was Edie’s first Warhol film. She arrived at the Factory just as Gerard Malanga was doing his little torture job in

Vinyl

on Ramsey Hellmann, this runaway kid from Canada. They’d brought in some real sado-masochists to do the number right, with razor blades and candles. They were very serious, with their leather and all that. Edie had come in at the last moment—no rehearsals, nothing. I thought she was going to demolish all the work I had done. Andy propped her up on a huge trunk, smoking a cigarette, and occasionally she flicked her ashes on this boy who was being tortured. She sat there, sort of stretched out, and the camera just went berserk looking at those eyes. The outfit she wore was certainly calculated . . . she had no breasts, but she had legs that didn’t quit, so why not show everybody the legs all the time? What do you do with legs like that in the middle of winter, I don’t know . . . freeze to death?

Andy filming

The film became like one of those vehicles for a famous star, but if s somebody

else

who gets discovered . . . like Monroe in

Asphalt Jungle.

She had a five-minute role and everyone came running: “Who’s the blonde?”

GERARD MALANGA

In

Vinyl

I was giving my long juvenfle-de-linquent’s soliloquy when Andy threw Edie into the film at the last minute. I was a bit peeved at the idea because it was an all-male cast. Andy said, ‘It’s okay. She looks like a boy.” And it worked out fine. She had covered her automobile-crash scar with a decoration like a tear drop. She said something you could barely hear on the sound track, otherwise she didn’t say anything. She didn’t get in my hair.

ONDINE

The Whole last scene was filmed with people on poppers—amyl nitrates—

Boom!

It seemed like the entire room was stoned. I mean

just out of it.

When the film was over, we went off in the hallways and up on the roof. I was in the hallway with Pierre’s lover, who was really beautiful. Pierre was up on the roof with somebody else. Somebody was in the bathroom with somebody. People did things on the couch.

In the middle of all that, Edie was staring, just staring. She couldn’t believe it. She was talking to Warhol, who was eating his hamburger, there was no way she wasn’t aware of it.

Well, after we saw a few reruns of

Vinyl,

some of us got an inkling of what was going on there with her in the Factory . . . a power that we hadn’t even suspected.

RONALD TAVEL

I wrote a great number of the Warhol films. Warhol and I were very uncomfortable together. I never knew what to say to him, and he never knew what to say to me. In fact, we almost never said anything. The only time we really worked together, co-directing for about a week, was with

kitchen.

Andy really liked it; he said it was the best script that I had done, and he liked it as a vehicle for Edie sedgwick.

As best as I can articulate about the average Warhol film, the way to work was to work for no meaning. Which is pretty calculated in itself: you work at something so that it means nothing. I did have one precedent—Gertrude Stein. In much of her work she tried to rob the words of meaning. So my problem as the scriptwriter was to make the scripts so they meant nothing, no matter how they were approached.

Edie and Gerard Malanga in the torture sequence,

Vinyl,

March, 1965

I worked on getting rid of characters. Andy had said, “Get rid of plot.” Of course, Samuel Beckett had done that in the Fifties, but he had retained his characters. So I thought what I could introduce was to get rid of character. That’s why the characters’ names in

Kitchen

are interchangeable. Everyone has the same name, so nobody knows who anyone is.

Andy and I would sit side by side like two Hollywood directors and tell the actors what to do, and sometimes Andy’d turn to me and say—especially when Roger Trudeau would hug Edie—“It looks just like a Hollywood movie.” That would bother him. He went for that sloppy, offhand, garbagy look. Edie forgot her lines a lot. If she didn’t know a line, she was to sneeze. That was the signal, so that someone behind the refrigerator could whisper it to her. There were other techniques—pages of script hidden among the junk on the kitchen table, or in the cabinets, so if the actors forgot their lines, they could go and pretend they were looking for a cup or a glass.

NORMAN MAILER

I think warhol’s films are historical documents. One hundred years from now they wI’ll look at

Kitchen

and see that incredibly cramped little set, which was indeed a kitchen; maybe it was eight feet wide, maybe it was six feet wide. It was photographed from a middle distance in a long, low medium shot, so it looked even narrower than that. You can see nothing but the kitchen table, the refrigerator, the stove, and the actors. The refrigerator hummed and droned on the sound track. Edie had the sniffles. She had a dreadful cold. She had one of those colds you get spending the long winter in a cold-water flat. The dialogue was dull and bounced off the enamel and plastic surfaces. It was a horror to watch. It captured the essence of every boring, dead day one’s ever had in a city, a time when everything is imbued with the odor of damp washcloths and old drains. I suspect that a hundred years from now people wI’ll look at Kitchen and say, “Yes, that is the way it was in the late Fifties, early Sixties in America. That’s why they had the war in Vietnam. That’s why the rivers were getting polluted. That’s why there was typological glut. That’s why the horror came down. That’s why the plague was on its way.”

Kitchen

shows that better than any other work of that time.

GEORGE PLIMPTON

Any number of influences must have been involved with Andy’s filmmaking. I remember riding in a large freight elevator with Andy in the early sixties—it may have been the one that rose slowly to the Factory—and mentioning in passing that I

had been reading an account in

The New Yorker

of an Erik Satie musical composition being played over and over for eighteen hours by relays of pianists in a recital room in Carnegie Hall. Apparently the composer had specified that this was how he wanted the piece—which was only a minute and a half long—performed. I mentioned it to Andy only because I thought he might be vaguely interested—after all, he was doing these eight-hour films of people sleeping. It never occurred to me that he knew of this concert, or of Satie, since it wouldn’t have surprised me a bit if he’d never

heard

of Satie. His reaction startled me. He said, “Ohhh, ohhh, ohhh!” I’d never seen his face so animated. It made a distinct impression. Between ohhh’s he told me that he’d actually

gone

to the concert and sat through the whole thing. He couldn’t have been more delighted to be telling me about it.