Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492-1830 (93 page)

Read Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492-1830 Online

Authors: John H. Elliott

Tags: #Amazon.com, #European History

BOOK: Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492-1830

11.99Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Imperial weakness, if measured by the failure of the British state to appropriate more of the wealth generated by the colonial societies and to intervene more effectively in the management of their domestic affairs, proved to be a source of long-term strength for those societies themselves. They were left to make their own way in the world, and to develop their own mechanisms for survival. This gave them resilience in the face of adversity, and a growing confidence in their capacity to shape their own institutions and cultural patterns in the ways best suited to their own particular needs. Since the motives for the foundation of distinctive colonies varied, and since they were created at different times and in different environments over the span of more than a century, there were wide variations in the responses they adopted and in the character their societies assumed. This diversity enriched them all.

Yet, for all their diversity, the colonies also had many features in common. These did not, however, derive, as in Spain's American empire, from the imposition by the imperial government of uniform administrative and judicial structures and a uniform religion, but from a shared political and legal culture which gave a high priority to the right of political representation and to a set of liberties protected by the Common Law The possession of this culture set them on the path that led to the development of societies based on the principles of consent and the sanctity of individual rights. In the crisis years of the 1760s and 1770s this shared libertarian political culture proved sufficiently strong to rally them in defence of a common cause. In uniting to defend their English liberties, the colonies ensured the continuation of the creative pluralism that had characterized their existence from the start.

Yet the story could have been very different. If Henry VII had been willing to sponsor Columbus's first voyage, and if an expeditionary force of West Countrymen had conquered Mexico for Henry VIII, it is possible to imagine an alternative, and by no means implausible, script: a massive increase in the wealth of the English crown as growing quantities of American silver flowed into the royal coffers; the development of a coherent imperial strategy to exploit the resources of the New World; the creation of an imperial bureaucracy to govern the settler societies and their subjugated populations; the declining influence of parliament in national life, and the establishment of an absolutist English monarchy financed by the silver of America.15

As it happened, matters turned out otherwise. The conqueror of Mexico showed himself to be a loyal servant of the King of Castile, not the King of England, and it was an English, not a Spanish, trading company that commissioned an ex-privateer to found his country's first colony on the North American mainland. Behind the cultural values and the economic and social imperatives that shaped the British and Spanish empires of the Atlantic world lay a host of personal choices and the unpredictable consequences of unforeseen events.

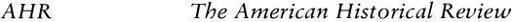

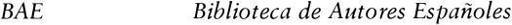

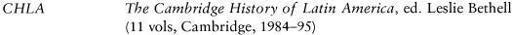

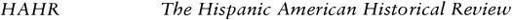

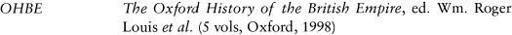

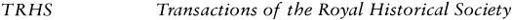

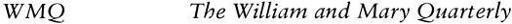

Abbreviations

Notes

Introduction. Worlds Overseas

1. Cited by Carla Rahn Phillips, Life at Sea in the Sixteenth Century. The Landlubber's Lament of Eugenio de Salazar (The James Ford Bell Lectures, no. 24, University of Minnesota, 1987), p. 21.

2. For numbers of emigrants, see Ida Altman and James Horn (eds.), `To Make America'. European Emigration in the Early Modern Period (Berkeley, Los Angeles, Oxford, 1991), p. 3.

3. Enrique Otte, Cartas privadas de emigrantes a Indias, 1540-1616 (Seville, 1988), letter 73. For life at sea on the Spanish Atlantic see Pablo E. Perez-Mallaina, Spain's Men of the Sea. Daily Life on the Indies Fleets in the Sixteenth Century (Baltimore and London, 1998).

4. Cited in David Cressy, Coming Over. Migration and Communication between England and New England in the Seventeenth Century (Cambridge, 1987), p. 157.

5. See Daniel Vickers, `Competency and Competition: Economic Culture in Early America', WMQ, 3rd set., 47 (1990), pp. 3-29.

6. For the cognitive problems facing Early Modern Europeans in America, see Anthony Pagden, The Fall of Natural Man (revised edn, Cambridge, 1986), especially the Introduction and ch. 1.

7. David Hume, Essays. Moral, Political and Literary (Oxford, 1963), p. 210.

8. See Antonello Gerbi, The Dispute of the New World. The History of a Polemic, 1750-1900, trans. Jeremy Moyle (Pittsburgh, 1973).

9. Louis Hartz, The Founding of New Societies (New York, 1964), p. 3.

10. Turner first advanced his hypothesis in his 1893 lecture to the American Historical Association on `The Significance of the Frontier in American History' (reprinted in Frontier and Section. Selected Essays of Frederick Jackson Turner (Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1961)).

11. For a summary of the criticisms, see Ray Allen Billington, `The American Frontier', in Paul Bohannen and Fred Plog (eds), Beyond the Frontier. Social Process and Cultural Change (Garden City, NY11967), pp. 3-24.

12. See, for Latin America, Alistair Hennessy, The Frontier in Latin American History (Albuquerque, NM, 1978), and Francisco de Solano and Salvador Bernabeu (eds), Estudios (nuevos y viejos) sobre la frontera (Madrid, 1991).

13. Herbert E. Bolton, `The Epic of Greater America', reprinted in his Wider Horizons of American History (New York, 1939; repr. Notre Dame, IL, 1967). See also Lewis Hanke (ed.), Do the Americas Have a Common History? (New York, 1964), and J. H. Elliott, Do the Americas Have a Common History? An Address (The John Carter Brown Library, Providence, RI, 1998).

14. Although, for a recent bold attempt to grapple with the question in short compass, see Felipe Fernandez-Armesto, The Americas. A Hemispheric History (New York, 2003).

15. Beginning with Frank Tannenbaum's seminal and provocative book, Slave and Citizen. The Negro in the Americas (New York, 1964).

16. See in particular Altman and Horn (eds), `To Make America', and Nicholas Canny (ed.), Europeans on the Move. Studies on European Migration, 1500-1800 (Oxford, 1994). For the now fashionable concept of 'Atlantic History', in which slavery and emigration are important players, see Bernard Bailyn, Atlantic History. Concept and Contours (Cambridge, MA and London, 2005), David Armitage and Michael J. Braddick (eds), The British Atlantic World, 1500-1800 (New York, 2002), and Horst Pietschmann (ed.), Atlantic History and the Atlantic System (Gottingen, 2002).

17. Ronald Syme, Colonial Elites. Rome, Spain and the Americas (Oxford, 1958), p. 42.

18. James Lang, Conquest and Commerce. Spain and England in the Americas (New York, San Francisco, London, 1975).

19. Claudio Veliz, The New World of the Gothic Fox. Culture and Economy in British and Spanish America (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 1994). See my review, `Going Baroque', New York Review of Books, 20 October 1994.

20. For discussions of the problems of comparative history see George M. Frederickson, `Comparative History', in Michael Kammen (ed.), The Past Before Us (New York, 1980), ch. 19, and John H. Elliott, `Comparative History', in Carlos Barra (ed.), Historia a debate (3 vols, Santiago de Compostela, 1995), 3, pp. 9-19, and the references there given.

Other books

Casca 21: The Trench Soldier by Barry Sadler

Nigella Christmas: Food, Family, Friends, Festivities by Nigella Lawson

None of this Ever Really Happened by Peter Ferry

Teacher Beware (A Grace Ellery Romantic Suspense Book 1) by Charlotte Raine

El amante de Lady Chatterley by D. H. Lawrence

No Return by Zachary Jernigan

Otogizoshi: The Fairy Tale Book of Dazai Osamu (Translated) by Dazai, Osamu

The Rowing Lesson by Anne Landsman

Fourth Bear by Jasper Fforde

His Captive Bride by Suzanne Steele