Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (43 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

Example 9.1.

The “Mill Theme”

The spark that will eventually set fire to Julie and Billy has already been lit in the pantomimed prelude to act I.

16

During this prelude we see that Billy “takes his mind off his work” when he watches Julie and that she gains his attention in part by being the only person who does not “sway unconsciously with the rhythm of his words.” The description of the prelude’s action points out (parenthetically) that “Billy’s attitude to Julie throughout this scene is one of only casual and laconic interest.” Although he makes a point of finding the last place on the carousel for Julie, he then “dismisses her from his mind.” When

he later waves “patronizingly,” the omniscient description notes that “it means nothing to him,” but that “it means so much to her that she nearly falls!”

17

“If I Loved You,” the climactic moment in the following Bench Scene (act I, scene 1), reinforces these discrepancies in emotional intensity and awareness between the principals. Julie sings as a young woman already in love; Billy, although he admits to having noticed Julie at the carousel “three times before today” (she has actually been there far more often) sings, if not about a hypothetical love, about a love that he does not yet comprehend. Thus Billy can truthfully assert that if he loved Julie he would be “scrawny and pale,” and “lovesick like any other guy.” So far none of these symptoms has appeared. In fact, Billy does not realize until act II, scene 5, what Mrs. Mullin, the jealous, older, and less desirable carousel proprietress, has understood only too well as early as the prelude. Already in the pantomimed introduction Mrs. Mullin has demonstrated that, like Julie, she is enamored of Billy. Also in the prelude Mrs. Mullin has observed his unique attraction to Julie. We learn later that Mrs. Mullin correctly perceived that this peculiar young woman posed a serious threat both to her business—the other young women would patronize the carousel less ardently if Billy were romantically attached—and to any more personal relationship she might enjoy with her favorite barker.

Carousel

, prelude to act I. Jan Clayton and John Raitt on the carousel (1945). Museum of the City of New York. Theater Collection.

Although Rodgers and Hammerstein have the two love-struck mill workers, Carrie and Julie, sing the same tune, “You’re a Queer One, Julie Jordan,” Rodgers musically differentiates the sharp character distinctions drawn by Hammerstein. He does this by contrasting Carrie’s even eighth-note rhythms (“You are quieter and deeper than a well”) with Julie’s dotted eighths and sixteenths (“There nothin’ that I keer t’choose t’ tell”) (

Example 9.2a

); revealingly, Billy will whistle Julie’s dotted rhythms rather than Carrie’s even ones (

Example 9.2b

). A clue to Rodgers’s intention might be found in his autobiography,

Musical Stages

, where he discusses how “It Might as Well Be Spring,” from the Rodgers and Hammerstein film musical

State Fair

(

Example 9.2c

), serves as “a good example of the way a tune can amplify the meaning of its lyric.”

18

Rodgers continues: “The first lines are: ‘I’m as restless as a willow in a wind storm, / I’m as jumpy as a puppet on a string.’ Taking its cue directly from these words, the music itself is appropriately restless and jumpy.”

19

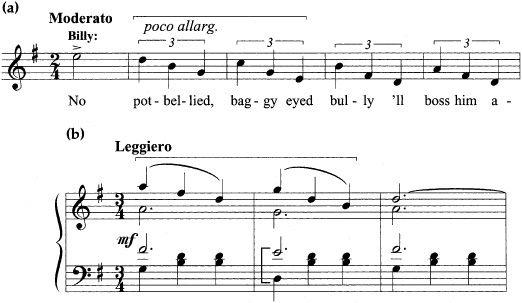

Example 9.2.

“Jumpy” rhythms in

Carousel

and

State Fair

(a) Julie and Carrie Sequence (

Carousel

)

(b) Scene Billy and Julie (

Carousel

)

(c) “It Might As Well Be Spring” (

State Fair

)

(d) Julie and Carrie Sequence (

Carousel

)

Clearly, Julie’s dotted rhythms when she sings “There’s nothin’ that I keer t’ choose t’

tell

,” almost identical in pitch to Carrie’s “You are quieter and deeper than a

well

,” successfully contrasts Julie’s restlessness with Carrie’s stability. When Julie tells Carrie that she likes “to watch the river meet the sea” (

Example 9.2d

), Rodgers presents a dotted melodic line filled with wide leaps that are unmistakably “jumpy as a puppet on a string.” Once Rodgers has established Julie’s sharp rhythmic profile in her opening exchange with Carrie, he shows Julie’s influence over her friend when Carrie adopts dotted rhythms to conclude their sung exchange (“And as silent as an old Sahaira Spink!”). More significantly, Julie’s dotted rhythms return when Billy reprises “You’re a queer one” after Carrie’s “Mister Snow” and Julie repeats her dotted jumpy melodic line to the words “I reckon that I keer t’ choose t’ stay.”

In the closing moments of the first act, Billy’s imaginary daughter, appropriately enough, will share Julie’s restlessness and her dotted rhythms. By the time Billy sings the “My little girl” portion of his “Soliloquy,” dotted rhythms have acquired a strong association with Julie, and by extension her as-yet-unborn daughter, Louise. Thus when Billy imagines his daughter as “half again as bright” and a girl who “gets hungry every night,” Rodgers has the future father sing Julie’s dotted rhythms. True to her character, in the second act Julie’s “What’s the Use of Wondrin’” also makes persistent use of dotted rhythms. On this occasion, however, Rodgers captures Julie’s newly acquired inner peace when he replaces with more sedate scales the jumpy melodic leaps that characterized her conversations with Carrie and Billy in act I, scene 1.

Rodgers also gives dramatic meaning to another distinctive rhythm in

Carousel

: the triplet. The main association between triplets and the principal lovers occurs when each attempts to answer what would happen if

they loved the other in the song “If I loved you.” The “hidden” triplets in their response to this subjunctive (

Example 9.3a

) reinforce the unreality and hesitation that matches the lines “Time and again I would try to say” and “words wouldn’t come in an easy way.” Not only do these words appear on the weak beats (second and fourth) of their measures–in marked contrast to the triplets in “Many a New Day” from

Oklahoma!

(

Example 3.1b

)—they are invariably tied to the stronger beats (first and third).

Of course, the imagined musical responses of Julie and Billy nevertheless reveal the truth that Julie is hiding from Billy and Billy from himself: the two misfits in fact are already in love. Although their desire for verbal communication is great (“Time and again I would try to say all I’d want you to know” or “Longing to tell you, but afraid and shy”), the pair must rely on music to express their deepest feelings. Words do not “come in an easy way.” Most poignantly, as if to reflect the painful truth of the few words they do sing, within a few months Billy indeed will be leaving Julie “in the mist of day.”

Just as Billy adopts Julie’s dotted rhythms in his “Soliloquy,” he will adopt in this central (and earliest-composed song) the triplets that he shared with Julie in “If I Loved You.” In contrast to the hesitant tied triplets of his duet with Julie, however, Billy in his private “Soliloquy” sings “Many a New Day”-type triplets that stand alone when he envisions having a daughter (compare

Example 9.3b

with

Example 3.1b

).

20

After Billy’s death, triplets also provide a brief but distinctive contrast in the release of Julie’s “What’s the Use of Wondrin’” to the ubiquitous dotted rhythms of the main melody.

Example 9.3.

Triplets in “If I Loved You” and “Soliloquy”

(a) “If I Loved You”

(b) “Soliloquy”

It makes musical sense, of course, for Rodgers to fill his prelude with waltzes to accompany the swirling of the carousel. But marches and polkas would be equally suitable. Rodgers knew, however, that waltzes, although capable of expressing a variety of meanings and emotions, had been associated with love ever since Viennese imports had dominated Broadway in the decade before World War I.

21

The most familiar waltz musical then and now was and is Lehár’s

The Merry Widow

, the work that launched an operetta invasion on Broadway in 1907. But waltzes had also figured prominently in 1920s operetta. Several of these featured lyrics by Hammerstein himself, including “You Are Love” in

Show Boat

. Later, in

The King and I

’s “Hello, Young Lovers” and

South Pacific

’s “A Wonderful Guy” Rodgers gives Anna Leonowens and Nellie Forbush waltzes when they sing of love, and Nellie’s temporarily rejected suitor Emile De Becque sings a waltz lamenting a lost love in “This Nearly Was Mine.”

In

Carousel

waltzes are associated either with the carousel itself, as in the procession of the several sharply defined waltzes that make up the pantomimed prelude, or in the chorus of community solidarity that characterizes the main tune of “A Real Nice Clambake.” Rodgers and Hammerstein therefore match the absence of directly expressed love between Billy and Julie by

not

allowing them to sing a waltz. Only when Billy sings his successions of triplets in his “Soliloquy” does Rodgers suggest a waltz (

Example 9.4a

), a suggestion that is reinforced with a melodic fragment identical to the melody of the final carousel waltz (

Example 9.4b

). Characteristically, Billy must keep his waltzes, as well as his expression of love, to himself.

As early as the 1920s, Rodgers strove to create musicals in which songs were thoroughly integrated into a dramatic whole. In his finest efforts with Hart, including

On Your Toes

and

Pal Joey

, and in his first collaboration with Hammerstein,

Oklahoma!

, Rodgers often succeeded in making the songs flow naturally from the dialogue and express character. But it was not until

Carousel

that Rodgers created a thoroughly unified musical score which also achieved a truly convincing coordination (i.e., integration) between music and dramatic action. Earlier, in

On Your Toes, Pal Joey

, and

Oklahoma!

Rodgers used the technique of thematic transformation for dramatic purposes, but the resulting musical unity did not always reinforce a drama generated by musical forces.