Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (49 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

Even those who love to hate Broadway musicals make an exception for

Guys and Dolls

and consider this show one of the most entertaining and perfect ever. Although Gershwin’s

Porgy and Bess

and perhaps Bernstein’s

Candide

would later overshadow Loesser’s next show in popularity or critical approbation,

The Most Happy Fella

continues to boast the longest initial run, 678 performances, of any Broadway work prior to the 1980s that might claim an operatic rubric. As a tribute to its anticipated appeal as well as its abundance of music, its cast album was the first to be recorded in a nearly complete state, on three long-playing records.

In contrast to the instant and sustained appeal and unwavering stature of

Guys and Dolls

, however, the popularity and stature of

The Most Happy Fella

has evolved more slowly and less completely. In one prominent sign of its growing popularity and acclaim in the United States, the 1990–1991 Broadway season marked the appearance (with generally positive critical press) of two new productions, one with the New York City Opera and one on Broadway.

1

Despite lingering controversy regarding its ultimate worth,

The Most Happy Fella

is clearly gaining in both popular acclaim and critical stature and is even receiving some serious scholarly attention.

2

Like fellow composer-lyricist Stephen Sondheim two decades later, Loesser (1910–1969) gained initial distinction as a lyricist.

3

Unlike Sondheim, who had been writing music to complement his lyrics since his teens, only after a decade of professional lyric-writing could Loesser be persuaded to compose his own music professionally. He scored a bull’s eye on his very first try, “Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition” (1942), one of the most popular songs of World War II. Earlier he wrote his first published song lyrics, “In Love with the Memory of You” (1931), to music composed by William Schuman, the distinguished classical composer and future president of the Juilliard School and the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. In an unusual coincidence Loesser made his Broadway debut (as a lyricist) for the same ill-fated revue,

The Illustrator’s Show

(1936), that marked the equally inauspicious Broadway debut of Frederick Loewe, twenty years before

My Fair Lady

and

The Most Happy Fella

.

Loesser began a decade of film work more successfully the next year with his song, “The Moon of Manakoora.” Film collaborations with major Hollywood songwriters would soon produce lyrics to the Hoagy Carmichael chestnuts, “Heart and Soul” and “Two Sleepy People” (both in 1938), and song hits with Burton Lane and Jule Styne who, like Loesser, would soon be creating hit musicals on Broadway beginning in the late 1940s.

4

After “Praise the Lord,” Loesser, a composer-lyricist in the tradition of Berlin and Porter, would go on to compose other World War II popular classics, including

“What Do You Do in the Infantry” (in “regulation Army tempo”) and the poignant “Rodger Young,” and later a string of successful film songs that culminated in the Academy Award–winning “Baby, It’s Cold Outside,” featured in

Neptune’s Daughter

(1947).

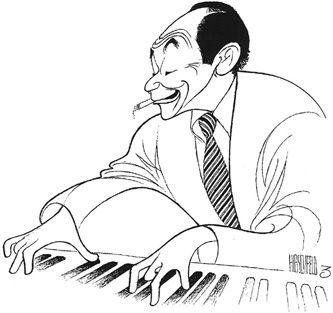

Frank Loesser. © AL HIRSCHFELD. Reproduced by arrangement with Hirschfeld’s exclusive representative, the MARGO FEIDEN GALLERIES LTD., NEW YORK.

WWW.ALHIRSCHFELD.COM

Clearly, by the late 1940s Loesser was ready for Broadway. Drawing on the star status of Ray Bolger and the experience of George Abbott (the writer-director of Rodgers and Hart’s

On Your Toes

, also starring Bolger, and the director of

Pal Joey

), fledgling producers Ernest Martin and Cy Feuer were prepared to take a calculated risk on Loesser’s music and lyrics with Abbott’s adaptation of Brandon Thomas’s still-popular comedy,

Charley’s Aunt

(1892). Unlike other musical settings of popular plays—including Loesser’s

The Most Happy Fella

, adapted from Sidney Howard’s Pulitzer Prize–winning but now mostly forgotten play,

They Knew What They Wanted

(1924)—

Where’s Charley?

(1948) never managed to surpass its progenitor. Nevertheless, this extraordinary Broadway debut became the first of Loesser’s four major hit musicals during a thirteen-year Broadway career (1948–1961). In the end, the composer-lyricist and one-time librettist would earn three New York Drama Critics Circle Awards (

Guys and Dolls, The Most Happy Fella

, and

How

to Succeed in Business without Really Trying

), two Tony Awards (

Guys and Dolls

and

How to Succeed

), and one Pulitzer Prize for drama (

How to Succeed

).

5

Where’s Charley?

was a well-crafted, old-fashioned Broadway show with sparkling Loesser lyrics and melodies. In order to show off a wider spectrum of Bolger’s talents, the character of Lord Fancourt Babberley (who impersonated Charley’s aunt in Thomas’s play) was excised, and much of the comedy revolved around Charley’s switching between two roles, Charley and his aunt, throughout the musical. Working against type, the opening duet, “Make a Miracle,” between the central character, Charley Wykeham (Bolger), and Amy Spettigue was a comic number rather than a love song. More typically, Charley’s formal expression of love, “Once in Love with Amy,” was a show-stopper directed not to Amy but to the audience, which Bolger asked to participate in his public tribute.

One year before Rodgers and Hammerstein offered a serious subplot with Lt. Joseph Cable and Liat in

South Pacific

, the lyrical principals of

Where’s Charley?

were the secondary characters, Jack Chesney and Kitty Verdun, who sing the show’s central love song, “My Darling, My Darling.” Despite this less conventional touch, at the end of the farce Charley (Bolger), without any dramatic justification other than his stature, was allowed to reprise and usurp his friend’s “My Darling, My Darling.” Such concessions were a small price to pay for a hit, even as late as 1948.

Life in Runyonland

Although

Where’s Charley?

was one of the most popular Broadway book musicals up to its time, the show hardly prepared critics and audiences for Loesser’s next show two years later.

6

Reviewers from opening night to the present day have given

Guys and Dolls

pride of place among musical comedies. Following excerpts from nine raves, review collector Steven Suskin remarks that “

Guys and Dolls

received what might be the most unanimously ecstatic set of reviews in Broadway history.”

7

In contrast to most musicals where some perceived flaw was manifest from the beginning (e.g., libretto weaknesses in

Show Boat

, the disconcerting recitative style in

Porgy and Bess

, the unpalatable main character in

Pal Joey), Guys and Dolls

was problem free. John McClain’s epiphany in the

New York Journal-American

that this classic was “the best and most exciting thing of its kind since

Pal Joey

” is representative.

8

Indeed, after

Pal Joey

in 1940 Loesser’s

Guys and Dolls

exactly ten years later is arguably the only musical comedy (as opposed to operetta) prior to the 1950s to achieve a sustained place in the Broadway repertory with its original book intact.

Although virtually no manuscript material is extant for

Guys and Dolls

, there is general agreement about the main outlines of its unusual genesis as told by its chief librettist Abe Burrows thirty years later.

9

After securing the rights to adapt Damon Runyon’s short story “The Idyll of Miss Sarah Brown” (and portions and characters drawn from several others, especially “Pick the Winner”),

Where’s Charley?

producers Feuer and Martin commissioned Hollywood scriptwriter Jo Swerling to write the book, and Loesser wrote as many as fourteen songs to match. Feuer and Martin then managed to persuade the legendary George S. Kaufman to direct. In a scenario reminiscent of

Anything Goes

and

One Touch of Venus

, where new librettists were brought in to rewrite a book, all of the above-mentioned

Guys and Dolls

collaborators concurred that Swerling’s draft of the first act failed to match their vision of Runyonesque comedy. Burrows was then asked to come up with a new book to support Loesser’s songs. As Burrows explains:

Loesser’s songs were the guideposts for the libretto. It’s a rare show that is done this way, but all fourteen of Frank’s songs were great, and the libretto had to be written so that the story would lead into each of them. Later on, the critics spoke of the show as “integrated.” The word “integration” usually means that the composer has written songs that follow the story line gracefully. Well, we did it in reverse. Most of the scenes I wrote blended into songs that were already written.

10

The legal aspects of Swerling’s contractual obligations has generated some confusion regarding the authorship of

Guys and Dolls

. The hoopla generated by the Tony Award–winning 1992 Broadway revival of

Guys and Dolls

reopened this debate and other wounds.

11

When novelist William Kennedy credited Burrows as “the main writer” in a feature article in the

New York Times

, he inspired a sincere but unpersuasive letter from Swerling’s son who tried to explain why the “myth” about Burrows’s sole authorship “just ain’t so.”

12

Although the full extent of Kaufman’s contribution remains undocumented, his crucial role in shaping

Guys and Dolls

cannot be overlooked or underestimated. Just as his earlier partner in riotous comedy, Moss Hart, would work intensively with Lerner on the

My Fair Lady

libretto several years later and may be responsible for a considerable portion of the second act, the uncredited Kaufman had a major hand in the creation as well as the direction of the universally admired

Guys and Dolls

libretto. Even more than most comic writers, Kaufman was fanatically serious about the quality and quantity of his jokes, and under his guidance Burrows removed jokes that were either too easy or repeated. In addition, Burrows followed Kaufman’s

advice to take the necessary time to “take a deep breath and set up your story.”

13

Burrows recalls that even six weeks after the show opened to unequivocally positive notices Kaufman “pointed out six spots in the show that weren’t funny enough.”

14

In contrast to

Pal Joey

, with its prominent melodic use of a leading tone that obsessively ascends one step higher to the tonic (e.g., B to C in “Bewitched”) as a unifying device,

Guys and Dolls

achieves its musical power and unity from the rhythms associated with specific characters. The “guys” and “dolls,” even when singing their so-called fugues, display a conspicuous amount of syncopation and half-note and quarter-note triplet rhythms working against the metrical grain—illustrated also by Reno Sweeney in

Anything Goes

(

Example 3.1

, p. 56), Venus and Whitelaw Savory in

One Touch of Venus

(

Example 7.2

, p. 148), and Tony in

West Side Story

(on the words “I just met a girl named Maria” in

Example 13.2b

, p. 285).

The clearest and most consistently drawn rhythmic identity occurs in Adelaide’s music. Even when “reading” her treatise on psychosomatic illness in “Adelaide’s Lament,” this convincing comic heroine adopts the quarter-note triplets at the end of the verses (“Affecting the upper respiratory tract” and “Involving the eye, the ear, and the nose, and throat”). By the time she translates the symptoms into her own words and her own song, the more common, rhythmically conventional eighth-note triplets are almost unceasing.

15

In order for Loesser to convince audiences that Sarah Brown and Sky Masterson are a good match, he needed to make Sarah become more of a “doll” like Adelaide; conversely, he needed to portray Sky as more gentlemanly than his crapshooting colleagues. He accomplishes the first part of this task by transforming Sarah’s rhythmic nature, giving the normally straitlaced and rhythmically even “mission doll” quarter-note triplets in “I’ll Know” and syncopations in “If I Were a Bell.”

16

Sarah must also cast aside her biases against the petty vice of gambling and learn that a man does not have to be a “breakfast eating Brooks Brothers type” to be worthy of her love. In her first meeting with Sky, she discovers a person who surpasses her considerable knowledge of the Bible (Sky emphatically points out that the Salvation Army sign, “No peace unto the wicked” is incorrectly attributed to Proverbs [23:9] instead of to Isaiah [57:21]). Soon Sky will reveal himself to be morally sound, genuinely sensitive, and capable of practicing what the Bible preaches. Not only does he refuse to take advantage of her physically in act I, but he will even lie to protect her reputation in act II.