Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (53 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

More frequently than not, heterogeneous twentieth-century classical music, especially American varieties, has been subjected to similar criticism. Music that combines extreme contrasts of classical and popular styles, of tonality and atonality, of consonance and dissonance, as found in Mahler, Berg, and Ives, often disturbs more than it pleases listeners who enjoy the more palatable stylistic heterogeneity of Mozart’s

Magic Flute

. Before the 1970s most critics and audiences found

Porgy and Bess

, with its hybrid mix of popular hit songs and seemingly less-melodic recitative, at least partially unsettling. In the following chapter it will be suggested that even in

My Fair Lady

one song, the popular “On the Street Where You Live,” whether or not it was inserted as a concession to popular tastes, clashes stylistically with the other songs in the show.

Similarly, the colliding styles of nineteenth-century Italian opera (“Happy to Make Your Acquaintance”) and Broadway show tunes (“Big D”) practically back-to-back in the same scene provoked strong negative reaction. What Loesser does in

The Most Happy Fella

is to use a popular Broadway style to contrast his Italian or Italian-inspired characters (and the operatic temperament of Tony’s eventual match, Rosabella) with their comic counterparts and counterpoints, Rosabella’s friend Cleo and her good-natured boyfriend Herman. Between the extremes of “How Beautiful the Days” and “Big D” lie songs like the title song and “Sposalizio,” which are more reminiscent of Italian popular tarantellas such as “Funiculi, Funiculà” than of Verdian opera. Even those who condemn Loesser for selling out cannot fault him for composing songs that are stylistically inappropriate.

Nor will the accusation stick that Loesser undermined operatic integrity by inserting unused “trunk songs” from other contexts. The sixteen sketchbooks tell a different story. In fact, among all of the dozens of full-scale songs and ariosos, only one song, “Ooh! My Feet,” can be traced to an earlier show.

43

The

sketchbooks reveal that Loesser conceived and developed the more popularly flavored “Standing on the Corner” and “Big D” exclusively for his Broadway opera (what Loesser himself described as a “musical with a lot of music”). In the case of the latter, the solitary extant draft of “Big D” is a rudimentary one from March 1954 (two years before the Boston tryout) that displays most of the rhythm but virtually none of the eventual tune.

44

Early rudimentary sketches for “Standing on the Corner” appear in the first sketchbook (August 1953) and continue in several gradual stages (December 1953 and February, May, and June 1954) before Loesser found a verse and chorus that satisfied him.

45

In “Some Loesser Thoughts,” another playbill essay, the composer notes his “feeling for what some professionals call ‘score integration,’” which for Loesser “means the moving of plot through the singing of lyrics.”

46

Significantly, Loesser acknowledges that his comic songs do not accomplish this purpose when he writes in his next sentence that “in ‘The Most Happy Fella’ I found a rich playground in which to indulge both my ‘integration’ and my Tin Pan Alley leanings.” His final remarks fan the fuel for those who would accuse Loesser of selling out by making “

LOVE

” the principal emphasis of his adaptation. For Loesser, not only is love “a most singable subject,” it remains a subject “which no songwriter dares duck for very long if he wants to stay popular and solvent.”

Loesser’s judgment that the Tin Pan Alley songs do not contribute to the “moving of plot” shortchanges the integrative quality of songs such as Cleo’s “Ooh! My Feet” and Herman’s “Standing on the Corner,” which tell us much about the characters who will eventually get together. Since one prefers to sit and the other to stand, even the concepts behind their songs reveal their complementariness. As a show-stopper in the literal sense, “Big D” ranks as perhaps the sole (and welcome) exception to the work’s stature as an integrated musical.

The principal characteristics that unify

The Most Happy Fella

musically do not always serve dramatic ends. The first of Loesser’s most frequent melodic ideas, the melodic sequence defined earlier (

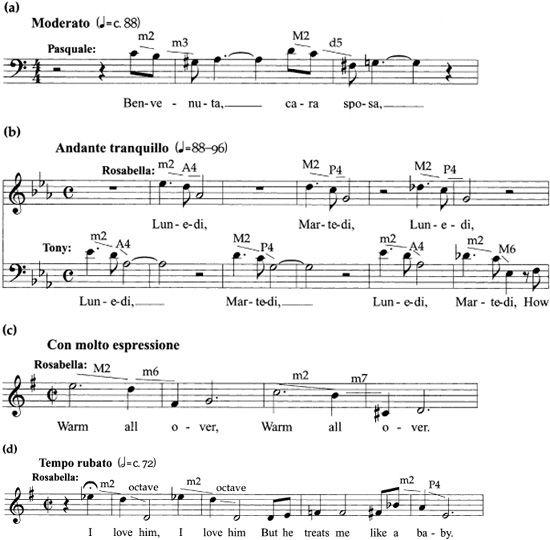

Example 11.4

) provides musical unity without dramatic meaning.

47

With only a few small exceptions, however, Loesser consistently employs another melodic unifier. This second melodic idea serves as the basis of a melodic family of related motives, melodies in which a descending minor or major second (a half-step or a whole-step) is followed by a wider descending leap that makes forceful dramatic points. A small but representative sample of this ubiquitous melodic stamp is shown in

Example 11.6

. Loesser’s keen dramatic instincts can be witnessed as the growing intensification of this large family of motives expands throughout the evening from “Benvenuta” (

Example 11.6a

) to “How Beautiful the Days” (

Example 11.6b

) and “Warm All Over” (

Example 11.6c

) to Rosabella’s heartfelt

arioso, “I Love Him,” when a minuscule minor second twice erupts into a full and uninhibited octave (

Example 11.6d

).

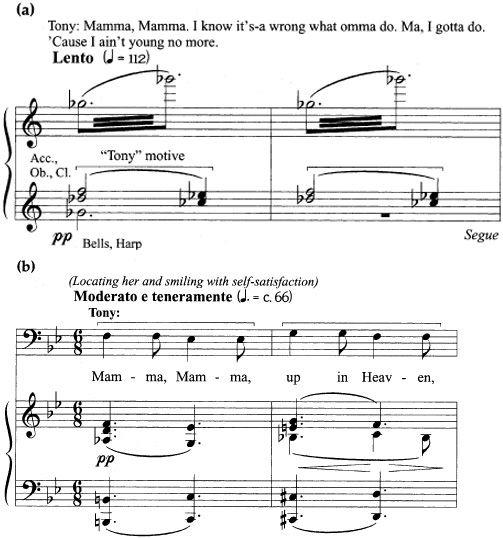

Loesser introduces a less familial and more individually significant musical motive after Tony has asked Joe for his picture (see the “Tony” motive in

Example 11.7a

). Convinced by his sister Marie that he “ain’t young no more,” “ain’t good lookin,’” and “ain’t smart,” the not-so-happy fella has the first of several chats with his deceased Mamma (act I, scene 2): “An’ sometime soon I wanna send-a for Rosabella to come down here to Napa an’ get marry. I gotta send-a Joe’s pitch.’”

48

The music that underscores Tony’s dialogue with his mother consists of a repeated “sighing” figure composed of descending seconds on strong beats (appoggiaturas), a familiar figure derived from eighteenth- and nineteenth-century operatic depictions of pain and loneliness, underneath a sustained string tremolo that contributes still further to the drama of the moment.

49

Example 11.6.

The family of motives in

The Most Happy Fella

(M = major; m = minor; d = diminished; A = augmented; P = perfect)

(a) “Benvenuta”

(b) “How Beautiful the Days”

(c) “Warm All Over”

(d) “I Love Him”

In act II, Marie again feeds her brother’s low self-image despite Rosabella’s assurance that Tony makes her feel “Warm All Over” (in contrast to the “Cold and Dead” response she felt after sleeping with Joe). Consequently, the still-unhappy central character “searches the sky for ‘Mamma’ and finds her up there,” and the original form of his “sighing” returns to underscore a brief monologue. Tony then sings a sad reprise of his sister’s didactic warning, “Young People,” with still more self-flagellating lyrics: “Young people gotta dance, dance, dance, / Old people gotta sit dere an’ watch, watch, watch. / Wit’ da make believe smile in da eye. / Young people gotta live, live, live. / Old people gotta sit dere an’ die.”

50

After the potent dramatic moment in the final scene of act II, Rosabella finally convinces Tony that she loves him, not out of pity for an aging invalid but “like a woman needs a man.” To celebrate this long-awaited moment Tony and Rosabella sing their rapturous duet, “My Heart Is So Full of You.” Tony announces that the delayed wedding party will take place that night, and everyone spontaneously dances a hoedown.

The newfound joy of this May-September mailorder romance is shortlived. Rosabella faints from the strain, discovers that she is pregnant with Joe’s baby, and asks Cleo for advice. Tony, with a new self-confidence and

overcome by love (he is also somewhat oblivious to Rosabella’s internal anguish), again communicates with his mother over the returning string tremolo and the “sighing” “Tony” motive (

Example 11.7a

). This time, however, when Tony sings to his mother, Loesser ingeniously converts the “sighing” motive into a passionate arioso of hope and optimism, “Mamma, Mamma” (

Example 11.7b

). Tony’s sighing motive will return briefly in the final scene of the show on the words “have da baby,” as Tony, “reflecting sadly,” decides to accept Rosabella’s moment of infidelity as well as its consequences. And as he did in “Mamma, Mamma” at the end of act II, Tony successfully converts a motive that had previously reflected sadness, loneliness, and self-pity into positive emotions throughout the ten passionate measures of the abbreviated aria in act III, “She gonna come home wit’ me.”

51

Example 11.7.

“Tony” motive

(a) original

(b) transformed

Just as Rosabella comes to express her growing love for Tony with ever-expanding intervals, Tony learns to channel the self-pity expressed in his sighing motive. By the end of the musical the “Tony” motive has been transformed into a love that allows him to put the well-being of another person ahead of himself and to understand how Rosabella’s mistake with Joe was the consequence of Tony’s own error when he sent Rosabella Joe’s picture rather than his own. As part of this metamorphosis Tony finally stands up to his sister. When Marie once again points out his age, physical unattractiveness, and lack of intelligence, the formerly vulnerable Tony responds to the final insult in this litany in underscored speech: “No! In da head omma no smart, ma, in da heart, Marie. In da heart!”

52

Loesser’s

The Most Happy Fella

, smart in the head as well as in the heart, has managed to entertain and move audiences as much as nearly any musical that aspires to operatic realms (Loesser’s denials notwithstanding).

Although it lacks the dazzling and witty dialogue, lyrics, and songs of its more popular—and stylistically more homogeneous—Broadway predecessor

Guys and Dolls

, Loesser’s musical story of Tony and his Rosabella offers what Burrows described as “a gentle something that wanted to ‘make them cry.’”

53

The Most Happy Fella

makes us cry.

Four years later Loesser himself was crying over the failure (ninety-seven performances) of the bucolic

Greenwillow

(1960). The show contained an excellent score, the best efforts of Tony Perkins in the leading role, and a positive review by Brooks Atkinson in the

New York Times

. Despite all this, Donald Malcolm would ridicule the show’s tone in the

New Yorker

when he wrote that the village of

Greenwillow

“makes Glocca Morra look like a teeming slum” and a village where “Brigadoon could be the Latin Quarter.”

54

The following year Loesser, again with

Guys and Dolls

librettist Burrows, succeeded in a more traditional urban musical comedy,

How to Succeed in Business without Really Trying

(1961). Unlike Tony in

The Most Happy Fella

, whose vulnerability and humanity, if not age, appearance, and intelligence, distinguishes him from other Broadway protagonists, the hero of Loesser’s next (and last) Broadway hit, J. Pierrepont Finch, is a boyish and aggressively charming Machiavelli who sings the show’s central love song to himself as he shaves before a mirror in the executive washroom (“I Believe in You”).

As its well-received 1995 Broadway revival starring Matthew Broderick further demonstrated,

How to Succeed

deserves recognition as one of the truly great satirical shows. In how many musicals can we laugh so uproariously about nepotism, blackmail, false pretenses, selfishness, and the worship of money, among many other human foibles. One example of Loesser’s comic originality and imagination in song is “Been a Long Day.” In this number, which might be described as a trio for narrator and twin soliloquies, a budding elevator romance is described in blow-by-blow detail through a third party before the future lovebirds manage to express their privately sung thoughts directly.