Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (56 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

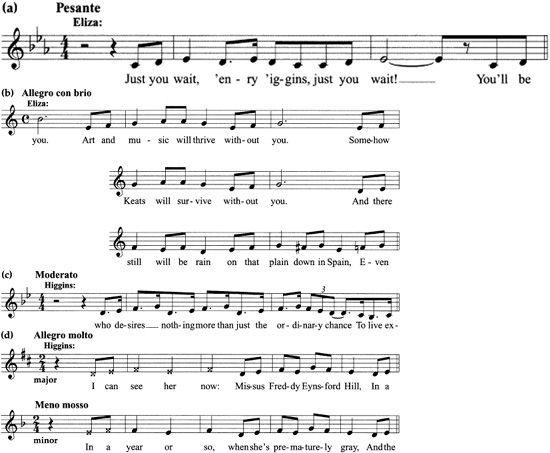

In act I of

My Fair Lady

, Eliza, in response to her initial humiliation prompted by her inability to negotiate the proper pronunciation of the letter “a” and to Higgins’s heartless denial of food (recalling Petruchio’s method of “taming” Kate in

Kiss Me, Kate

), sputters her ineffectual dreams of vengeance in “Just You Wait” (

Example 12.1a

).

46

Eliza sings a brief reprise of this song in act II after Higgins and the uncharacteristically inconsiderate Pickering display a callous disregard for Eliza’s part in her Embassy Ball triumph (“You Did It”). Eliza will also incorporate the tune at various moments in “Without You,” for example, when she sings “And there still will be rain on that plain down in Spain” (

Example 12.1b

).

My Fair Lady

, act I, scene 5. Julie Andrews and Rex Harrison (“In Hertford, Hereford, and Hampshire, hurricanes hardly ever happen.”) (1956). Museum of the City of New York. Theater Collection. Gift of Harold Friedlander. For a film still of this scene see p. 321.

Example 12.1.

“Just You Wait” and selected transformations

(a) “Just You Wait”

(b) “Without You”

(c) “I’m an Ordinary Man”

(d) “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face”

The opening phrase of the chorus in “Without You,” Eliza’s ode to independence, consists of a transformation into the major mode of “Just You Wait.” Its first four notes also inconspicuously recall Higgins’s second song of act I, “I’m an Ordinary Man,” when he first leaves speech for song on the words “who desires” (

Example 12.1c

). By this subtle transformation, audiences can subliminally hear as well as directly see that the tables have begun to turn as Eliza adopts Higgins’s musical characteristics. At the same time Higgins transforms Eliza into a lady, by the end of the evening Eliza (and her music) will have successfully transformed Higgins into a gentleman.

To reinforce this dramatic reversal, Higgins himself recapitulates Eliza’s “Just You Wait” material in both the minor and major modes of his final song, “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face” (

Example 12.1d

). At this point in the song Higgins is envisaging the “infantile idea” of Eliza’s marrying Freddy.

47

The verbal and dramatic parallels between Higgins’s and Eliza’s

revenge on their respective tormentors again suggest the reversal of their roles through song.

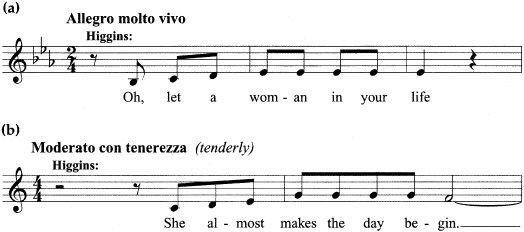

Higgins’s “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face” in act II also offers a musical demonstration of a dramatic transformation needed to convince audiences that Eliza’s return is as plausible as it is desirable. In the fast sections of “I’m an Ordinary Man” in act I, Higgins explains the discomforting effect of women on his orderly existence (

Example 12.2a

). Higgins’s dramatic transformation in his final song is most clearly marked by tempo and dynamics, but the melodic change is equally significant if less immediately obvious.

48

As shown in

Example 12.2b

, no longer does Higgins move up an ascending scale to reach his destination like a “motor bus” (Eliza’s description in Shaw’s act V). For one thing, the destination of the opening line, “She almost makes the day begin,” is the fourth degree of the scale (F in the key of C) on the final syllable rather than the first degree. For another, Higgins now precedes the resolution with the upper note G to soften the momentum of the ascending scale. Thus a lyrical Higgins, who sings more and talks less, conveys how he misses his Eliza. Eventually within the song this lyricism (to be sung

con tenerezza

or tenderly) will conquer the other side of his emotions, embodied in his dream of Eliza’s humiliation.

The reuse of “Just You Wait” and the transformation of the “but let a woman in your life” portions of “I’m an Ordinary Man” into “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face” provide the most telling musical examples of Higgins’s dramatic transformation. The far less obvious transformation of “I’m an Ordinary Man” into “Without You” mentioned earlier (

Example 12.1c

) provides additional musical evidence of the power reversal between Higgins and Eliza in the second act of

My Fair Lady

.

49

Example 12.2.

“I’m an Ordinary Man” and “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face”

(a) “I’m an Ordinary Man”

(b) “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face”

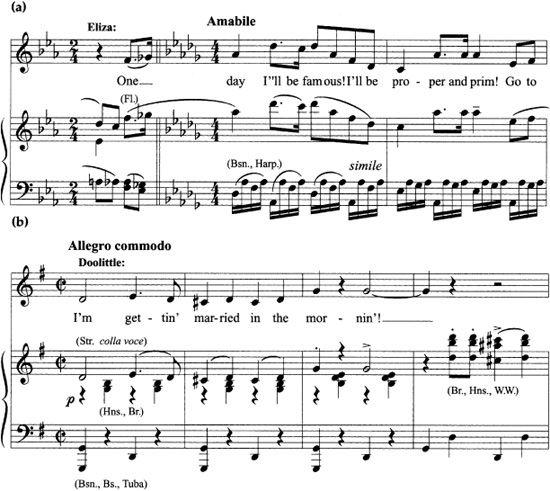

Although they lack the immediate recognizability of these melodic examples, the most frequent musical unities are rhythmic ones, with or without attendant melodic profiles. The middle section of “Just You Wait,” for example, anticipates the rhythm of “Get Me to the Church on Time” (

Example 12.3

). The eighteenth-century Alberti bass in the accompaniment of this section, which suggests the propriety of classical music, is also paralleled in the second act song of Eliza’s father when he decides to marry and thereby gain conventional middle-class respectability.

It is possible that Lerner and Loewe intended to link the central characters rhythmically by giving them songs that begin with an upbeat. In act I, both parts of Higgins’s “Ordinary Man,” the main melody of Doolittle’s “A Little Bit of Luck,” and Eliza’s “I Could Have Danced All Night” all begin with three-note upbeats. Eliza’s “Just You Wait,” Freddy’s “On the Street Where You Live,” and “Ascot Gavotte” each open with a two-note upbeat and “The Rain in Spain” employs a one-note upbeat.

Dramatic meaning for all these upbeats may be found by looking at the two songs in act I that begin squarely on the downbeat, “Why Can’t the English?” and “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly?” Significantly, these songs, the first two of the show, are rhetorical questions sung by Higgins and Eliza, respectively, before their relationship has begun. Clearly Higgins, in speaking about matters of language and impersonal intellectual matters, plants his feet firmly on solid ground. Similarly, the strong downbeats of Eliza’s opening song demonstrate her earthiness and directness. Once Higgins has encountered Eliza in his study and sings “I’m an Ordinary Man,” Lerner and Loewe let us know that Higgins is on less firm territory and can no longer begin his songs on the downbeat. After Eliza begins her lessons with Higgins, she too becomes unable to begin a song directly on the downbeat. As Doolittle becomes conventional and respectable, he too will begin respectably on the downbeat in his second-act number, “Get Me to the Church On Time.”

50

Example 12.3.

“Just You Wait” and “Get Me to the Church on Time”

(a) “Just You Wait” (middle section)

(b) “Get Me to the Church on Time” (opening)

Although Eliza transforms Higgins’s “Ordinary Man” in “Without You,” complete with upbeat, moments later she manages to demonstrate to Freddy that she can once again begin every phrase of a song on the downbeat, as she turns the Spanish tango of “The Rain in Spain Stays Mainly in the Plain” into the faster and angrier Latin rhythms of “Show Me.” Tellingly, Higgins never regains his ability to begin a song on the downbeat. Especially revealing is his final song, “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face,” which retains the three-note upbeat of his own “Ordinary Man” (“but let a woman in your life”) and Eliza’s euphoric moment in act I, “I Could Have Danced All Night.”

During the New Haven tryouts a few songs continued to present special problems. One of these songs, “Come to the Ball,” Lerner and Loewe’s second attempt to give Higgins a song of encouragement for Eliza prior to the Embassy Ball, was dropped after one performance.

51

Although Lerner never seemed to accept its removal, his more objective collaborators, Loewe and

especially director Moss Hart, understood why the show works better for its absence: while it endorses Eliza’s physical beauty, it simply does not offer her any other reason to attend the ball. Despite the current predilection of reinstating deleted numbers from Broadway classics, it seems unlikely that audiences will soon be hearing “Come to the Ball” in its original context.

The crucial role of Hart (the librettist of

Lady in the Dark

) in the development of Lerner’s book should not go unnoticed. Even if the full extent of his contribution cannot be fully measured, Lerner readily acknowledged that the director went over every word with the official librettist over a four-day marathon weekend in late November 1955.

52

Several of Hart’s major suggestions during the rehearsal and tryout process can be more accurately gauged. In addition to his requesting the deletion of “Come to the Ball,” we know from Lerner’s autobiography that Hart persuaded Lerner and Loewe to remove “a ballet that occurred between Ascot and the ball scene and ‘Say a Prayer for Me Tonight.’”

53

To fill the resulting gap near the end of act I, Lerner “wrote a brief scene which skipped directly from Ascot to the night before the ball.”

54

The other major song marked for extinction after opening night in New Haven was “On the Street Where You Live.” In both his autobiography and “An Evening with Alan Jay Lerner” presented at New York’s 92nd Street Y in 1971, Lerner discussed the negative response to this song, his own desire to retain it, his failure to understand why it failed, and his solution to the problem several days later.

55

For Lerner, the “mute disinterest” that greeted this song was due to the fact that audiences were unable to distinguish Freddy Eynesford-Hill from the other gentlemen at Ascot.

56

Lerner’s autobiography relates how he gave Freddy a new verse to help audiences remember him; in his “Evening” at the Y, Lerner explains a revision in which for the sake of clarity Freddy has the maid ask him to identify himself by name. In Lerner’s view the positive response to this change was vindication enough. Certainly “On the Street Where You Live” remains the most frequently performed song outside the context of the show.