Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (58 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

Within the next three months Bernstein’s first “serious” classical works were performed in New York: the song cycle

I Hate Music

, the “Jeremiah” Symphony, the ballet

Fancy Free

, and, by the end of 1944, when the composer was twenty-six, his first Broadway hit,

On the Town

. Between

On the Town

and

West Side Story

the phenomenally eclectic composer, conductor, pianist, and educator composed three major theater works of enduring interest:

Trouble in Tahiti

(1952; with his own libretto and lyrics),

Wonderful Town

(1953; book by Joseph Fields and Jerome Chodorov and lyrics by Comden and Green), and

Candide

(1956; book by Lillian Hellman, lyrics by Richard Wilbur, John Latouche, Dorothy Parker, Hellman, and Bernstein).

Several published personal remembrances help sort out the complicated genesis of

West Side Story

. The first recollection was recorded in 1949 in “Excerpts from a

West Side Story

Log,” the year Robbins introduced his concept to two of his future collaborators, Laurents and Bernstein. Bernstein’s log, which originally appeared in the

West Side Story Playbill

, identifies major events and ideological turning points between Robbins’s initial idea and the opening night tryout in August 1957.

8

Nearly thirty years later the foursome (Robbins, Laurents, Bernstein, and Sondheim) met in 1985 as a panel to discuss their creation before an audience of the Dramatists Guild.

9

Valuable information on the genesis of

West Side Story

can also be found in excerpts from published interviews with those involved in the original production, a number of which appear in Craig Zadan’s

Sondheim & Co

.

10

Other important sources on the compositional process are contained in Bernstein’s letters to his wife, Felicia, who was visiting her family in Santiago, Chile, during the rehearsals and Washington tryouts; Sondheim’s “Anecdote” published in the song book

Bernstein on Broadway

; and a Bernstein interview with theater critic Mel Gussow published shortly after the composer’s death in 1990.

11

Despite some minor discrepancies in their 1985 recollection of

West Side Story

’s genesis, the four collaborators shed a great deal of light on the evolution of their masterpiece.

12

Moreover, their memory of compositional changes is almost invariably vindicated by the eight libretto drafts and various lyric sheets housed among the Sondheim papers in the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. The first of the libretto drafts is dated January 1956, two months after Sondheim joined the entourage, and the last was completed on July 19, 1957, approximately midway through the unprecedentedly long eight-week rehearsal schedule (twice the usual length).

13

Earlier versions of Bernstein’s

holograph piano-vocal scores are also available both in Wisconsin and in the Music Division of the Library of Congress.

From Bernstein’s log we learn that Robbins’s original “noble idea” in January 1949 was “a modern version of

Romeo and Juliet

set in slums at the coincidence of Easter-Passover celebration.”

14

Over the next four months Laurents drafted four scenes, and the original trio of collaborators discussed the direction of what was then known as

East Side Story

. Bernstein recorded that their goal was to write “a musical that tells a tragic story in musicalcomedy terms … never falling into the ‘operatic’ trap,” a show that would not “depend on stars” but must “live or die by the success of its collaborations.”

The next log entries appear six years later when Robbins-Laurents-Bernstein returned to their dormant idea. On June 7, 1955, Bernstein reported that the group remained excited and hypothesized that “maybe I can plan to give this year to Romeo—if

Candide

gets in on time.” By August 25 the trio had “abandoned the whole Jewish-Catholic premise as not very fresh,” replacing Jews and Catholics with rival gangs, the newly arrived Puerto Ricans (the future Sharks) and the “self-styled ‘Americans’” (the Jets).

East Side Story

had metamorphosed into

West Side Story

.

Since Robbins’s balletic conception entailed an unusually extensive musical score, Bernstein, who until then thought he could handle the lyrics himself, decided that he needed a lyricist after all. On November 14 he wrote that they had found “a young lyricist named Stephen Sondheim,” and described him as “ideal for this project.”

15

In the 1985 symposium Sondheim added that when he was signed on as “co-lyricist” (in an unspecified month in 1955) Laurents “had a three-page outline.”

16

In the sole entry of 1956 (March 17) Bernstein announced that

Romeo

would be “postponed for a year” to make way for

Candide

.

17

Not unlike

Candide

’s Professor Pangloss, Bernstein tried to put the best possible face on this delay. He then described the “chief problem” of the new “problematical work”: “To tread the fine line between opera and Broadway, between realism and poetry, ballet and ‘just dancing,’ abstract and representational,” and to “avoid being ‘messagy.’”

18

On February 1, 1957, Bernstein noted briefly that with

Candide

“on and gone … nothing shall disturb the project.” In the next entry (July 8), shortly after rehearsals had begun, Bernstein confirmed the wisdom of 1949 in not casting “‘singers,’” since “anything that sounded more professional would inevitably sound more experienced, and then the ‘kid’ quality would be gone.” On August 20, one day after the opening-night tryout in Washington, Bernstein made his final entry. With great enthusiasm and pride he assessed the successful artistic collaboration (“all writing the

same

show”). Together, the quartet had created a work that possessed a “theme as profound as love

versus hate, with all the theatrical risks of death and racial issues and young performers and ‘serious’ music and complicated balletics.”

19

Shortly before his death Bernstein revealed that the melody of “America,” portions of “Mambo” from “The Dance at the Gym” (both derived from a never-completed Cuban ballet called

Conch Town

begun in 1941), and the centrally important “Somewhere” and “Maria” were among the first musical ideas conceived.

20

Regarding the origins of “Somewhere” Bernstein explained: “‘Somewhere’ was a tune I had around and had never finished. I loved it. I remember Marc Blitzstein loved it very much and wrote a lyric to it just for fun. It was called ‘There Goes What’s His Name.’”

21

Larry Kert (the original Tony) placed Bernstein’s recollection about “Somewhere” more precisely when he remembered that “Somewhere” was “written about the time of

On the Town

” (1944), which would make this song the earliest musical antecedent of the future

West Side Story

.

22

Of equal importance is Bernstein’s recollection that at the time the musical was still

East Side Story

he “had already jotted down a sketch for a song called ‘Maria,’ which was operable in Italian or Spanish.”

23

Not only did Bernstein’s sketch have a “dummy lyric,” it “had those notes … the three notes of ‘Maria’ [that] pervade the whole piece—inverted, done backward.”

24

Stephen Sondheim (at piano) and Leonard Bernstein rehearsing

West Side Story

(1957). Museum of the City of New York. Theater Collection.

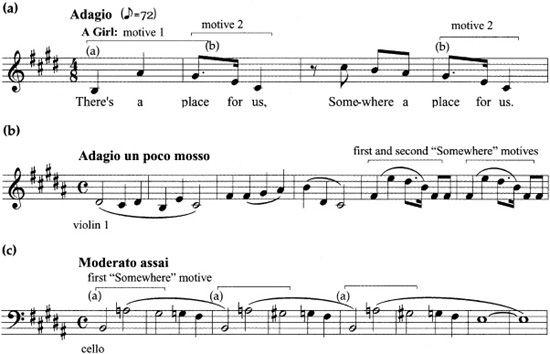

Example 13.1.

“Somewhere” in Beethoven and Tchaikovsky

(a) “Somewhere”

(b) Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 5, op. 73 (“Emperor”)

(c) Tchaikovsky:

Romeo and Juliet

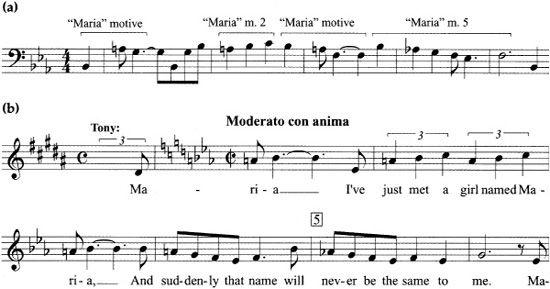

Example 13.2.

Blitzstein’s

Regina

and “Maria”

(a) Blitzstein’s

Regina

, Introduction to act I

(b) “Maria”

In the light of their contribution to the organic unity of the work, the knowledge that “Somewhere” and “Maria” were the first two songs drafted provides invaluable historical confirmation of the analytical conclusions that follow. Also striking, even if perhaps coincidental, is the fact that both of these pivotal songs bear unmistakable resemblances to music of Bernstein’s predecessors. The opening five pitches and rhythms of “Somewhere” (

Example 13.1a

) correspond closely to the fifth and six measures of the second movement of Beethoven’s E major Piano Concerto, op. 73, known as the “Emperor” (

major Piano Concerto, op. 73, known as the “Emperor” (

Example 13.1b

).

25

More significantly, the thrice-repeated three-note motive in the cello part at the conclusion of Tchaikovsky’s

Romeo and Juliet

Overture (

Example 13.1c

) is identical to the first three notes of Bernstein’s melody. Intended or not, “Somewhere” seems to begin where Tchaikovsky’s overture leaves off. Unlike borrowed material in other shows, a number of Bernstein’s central classical borrowings were apparently chosen for their programmatic and associative meaning.

26

The main tune of “Maria” is more obviously indebted to an aria from the opera

Regina

(based on Hellman’s

The Little Foxes

), composed by Bernstein’s mentor and friend, Marc Blitzstein (

Example 13.2

).

27

Perhaps not coincidentally,

Regina

premiered in 1949, the year Robbins conceived his “noble idea.” The exceedingly strong melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic similarities between “Maria” and the introductory music to act I of Blitzstein’s lesser known opera should be readily evident, even to those previously unfamiliar with the model.

Before intensive collaborative work began in 1956, several months after the entrance of Sondheim, the tangible evidence of

West Side Story

included a draft of several scenes, an outline of the remaining scenes, and substantial compositional work on two dramatically and musically central songs, “Somewhere” and “Maria.” The cross-fertilization between

West Side Story

and

Candide

of the previous year is also evident. In 1956 the comic duet now indelibly associated with Candide and Cunegonde, “Oh, Happy We,” had been considered for the bridal shop scene in

West Side Story

, and the song that was eventually placed there, “One Hand, One Heart,” was originally intended for

Candide

.

28

Until at least 1957, however, this future bridal shop song was located in the balcony scene, after which it was replaced by “Tonight” (see “Libretto Drafts 1 [January 1956] and 2 [Spring 1956]” in the online website). Another version of an unused

Candide

song, “Where Does It Get You in the End?,” served as the basis for “Gee, Officer Krupke,” a song that was not added until rehearsals in July.

29