Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (52 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

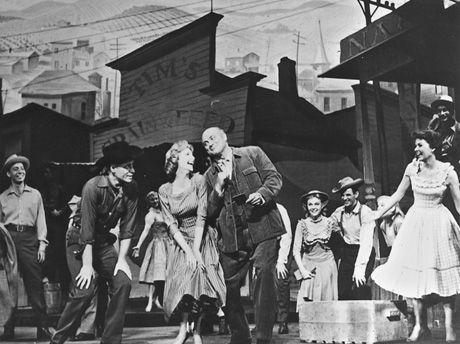

The Most Happy Fella

, act I, scene 2. Jo Sullivan and Robert Weede (1956). Photograph: Vandamm Studio. Museum of the City of New York. Theater Collection.

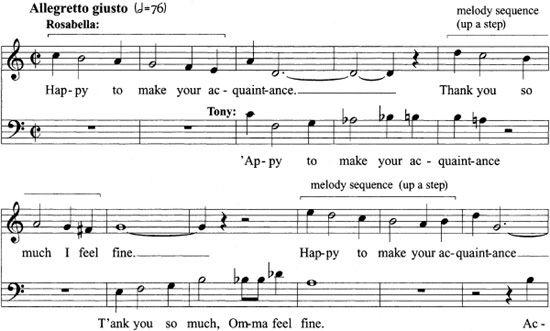

Example 11.4.

Melodic sequence and counterpoint in “Happy to Make Your Acquaintance”

Not surprisingly, the sketchbooks reveal something about the process by which Loesser worked out ways to combine melodies. What is seemingly less explicable is that Loesser took the trouble early in his compositional work to notate the familiar English round, “Hey Ho, Nobody Home” on a sketch entry labeled “Lovers in the Lane” (“Hi-ho lovers in the lane” is how Loesser’s text opens).

24

In the duet portions of “How Beautiful the Days,” Tony and Rosabella alternate entrances of the same melody much as Charley and Amy shared their tune in “Make a Miracle” and the would-be lovers in “Baby, It’s Cold Outside.” When it came to “Abbondanza,” the trio in which Tony’s servants take stock of the wedding feast, Loesser could not decide whether he wanted exact melodic imitation in triple meter (3/4 time) or a freer melodic counterpoint in duple meter (2/4 time).

25

Eventually he opted for the freer counterpoint and triple meter found in the published vocal score.

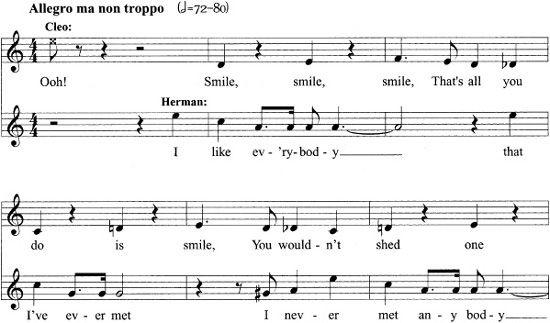

Loesser also included several songs that featured two simultaneous statements of independent but equally important melodies à la Berlin (non-imitative counterpoint). As “I Like Ev’rybody” for Herman and Cleo attests, Loesser did not reserve such contrapuntal complexity for his central romantic characters. When the song is introduced in act II, scene 4, Cleo starts it off with her tune. Then Herman sings the “main” tune against Cleo’s tune, now moved to the bass, where it was located in Loesser’s sketchbook.

26

At the reprise of the song late in the show (act III, scene 1), the now-compatible Herman and Cleo simultaneously sing their compatible melodic lines (

Example 11.5

).

In a short essay printed in the Imperial Theatre playbill Loesser described his initial resistance to the idea of adapting Howard’s play

They Knew What They Wanted

.

27

Before long, however, he realized that he could delete “the topical stuff about the labor situation in the 1920’s, the discussion of religion, etc.”

28

Loesser continues: “What was left seemed to me to be a very warm simple love story, happy ending and all, and dying to be sung and danced.”

29

Throughout his compositional work Loesser never lost sight of this central dramatic focus: the developing love and eventual fulfillment between the central protagonists, Tony and Rosabella.

Example 11.5.

Two-part counterpoint in “I Like Ev’rybody”

In keeping with the generally warmer and fuzzier expectations of a Broadway musical, Loesser added Cleo, Rosabella’s partner in waitressing drudgery in San Francisco, who receives a sitting job in Tony’s Napa Valley to rest her tired waitressing feet. He also gives Cleo a partner not found in Howard’s play, Herman, the likable hired hand who will win Cleo when he learns to make a fist. Cleo and Herman, like their obvious prototypes, Ado Annie and Will Parker in

Oklahoma!

, serve their function faithfully (in contrast to Adelaide and the relatively unsung Nathan in

Guys and Dolls

). They also make admirable comic lightweights (albeit with sophisticated counterpoint) to contrast with the romantic heavyweights, Tony and Rosabella.

Gone from the musical are not only the lengthy discussions about religion, but even the character of Father McGee, the loquacious priest who opposes the marriage between Tony and Amy (in the play Tony is in love with Amy rather than Rosabella). In Howard’s play, Father McGee shows no apparent concern about their age differences, nor is he motivated by the jealousy that motivates his newly created counterpart in the musical, Marie, Tony’s younger sister. Howard’s Father McGee responds negatively to the marriage for religious reasons: Tony’s mail-order bride is not a Catholic.

Other differences between the musical and the somewhat darker play might be briefly noted. Howard has Tony seek a mate outside his Napa

Valley Community because all the single women have slept with Joe, and he attributes Tony’s accident to drunkenness rather than fear of rejection. In the play, but not the musical, we learn that Tony’s fortune in the grape business stemmed from illegal earnings acquired during Prohibition. The play also contains a striking politically incorrect plot discrepancy. Only after the doctor tells Joe first that Amy (Rosabella) is pregnant does Joe tell Amy. In Howard’s play Joe offers to marry Amy and take her out of the Napa Valley; in Loesser’s adaptation Joe and Rosabella sing their private thoughts in the beginning of act II, but they never sing (or speak) directly after act I, and Joe leaves the community without knowing Rosabella’s condition.

In his obituary for his friend and collaborator, Burrows recalled an exchange that took place after

The Most Happy Fella

premiere on May 3, 1956: “I came out of the theater in great excitement, dashed up to Frank and began chattering away about the marvelous, funny stuff. Songs like ‘Standing on the Corner Watching All the Girls Go By.’ ‘Abbondanza,’ ‘Big D.’ Suddenly he cut me off angrily. ‘The hell with those! We know I can do that kind of stuff. Tell me where I made you cry.’”

30

Not content with the triumph of

Guys and Dolls

, Loesser wanted to do more in a musical than to entertain and write hit songs. He wanted to make audiences cry. And although the critical praise for Loesser’s most ambitious show about the Napa wine grower and his mail-order bride was far more equivocal than that enjoyed by

Guys and Dolls

, the view espoused here is that the achievement of

The Most Happy Fella

is equally impressive and the work itself arguably even greater Loesser.

31

Several New York tastemakers praised the show lavishly when it opened at the Imperial Theatre. Robert Coleman headed his review in the

Daily Mirror

with the judgment, “‘Most Happy Fella’ Is a Masterpiece” and subtitled this endorsement with “Loesser has performed a truly magnificent achievement with an aging play.”

32

John McClain of the

New York Journal-American

encapsulated his reaction in his title, “This Musical Is Great,” and underlying caption, “Loesser’s Solo Effort Should Last as One of Decade’s Biggest.”

33

In contrast to the unequivocal acclamation of

Guys and Dolls

and

My Fair Lady

(which opened less than two months before

Fella

), however, other New York critics then (and now) would respond negatively to the work’s operatic nature, its surfeit of music, and especially its stylistic heterogeneity, much as they had two decades earlier with

Porgy and Bess

. Predictably, some New York theater critics wanted a musical to be a traditional musical comedy or a Rodgers and Hammerstein sung play—anything but an opera in Broadway garb.

For these critics, a Janus-faced musical was a sin in need of public censure. Walter Kerr’s remarks in the

New York Herald Tribune

embody this distaste

for works that combine traditional Broadway elements with features associated with European opera: “Still, there’s a little something wrong with ‘Most Happy Fella’—maybe more than a little. The evening at the Imperial is finally heavy with its own inventiveness, weighted down with the variety and fulsomeness of a genuinely creative appetite. It’s as though Mr. Loesser had written two complete musicals—the operetta and the haymaker—on the same simple play and then crammed both into a single structure.”

34

Writing in the

New York Post

, Richard Watts Jr. notes the appropriateness of Loesser’s decision that “most of the music … suggests the more tuneful Italian operas.”

35

Nevertheless, Watts is grateful that “the composer has wisely added numbers which, without losing the mood, belong to his characteristic musical comedy manner, and these struck me as the most engaging of the evening.” By the end of his review Watts is urging Loesser to return to “his more successful American idiom.” George Jean Nathan, another critic who regularly expressed disdain for operatic pretensions in a musical, wrote in the

New York Journal-American

that Loesser “is more at home on his popular musical playground and that the most acceptable portions of his show are those which are admittedly musical comedy.”

36

Even

New York Times

theater critic Brooks Atkinson, who praised the “great dramatic stature” and “musical magnificence” of the show, voiced “a few reservations about the work as a whole” and concluded that the work “is best when it is simplest,” namely, the songs that most clearly reveal Loesser’s “connections with Broadway.”

37

Several weeks later the music critic Howard Taubman evaluated the work in the

New York Times

.

38

While he found much to praise in Loesser’s score, including the operatic duet “Happy to Make Your Acquaintance” and the quartet “How Beautiful the Days,” Taubman criticized in stronger terms than his theater colleague Loesser’s failure “to catch hold of a lyrical expression that is consistent throughout.” He also found fault with the composer-lyricist’s capitulation “to the tyranny of show business” in such numbers as “Standing on the Corner” and “Big D.” In the end Taubman defends his refusal to characterize

The Most Happy Fella

as an opera: “If it [music] is the principal agent of the drama, if the essential points and moods are made by music, then a piece, by a free-wheeling definition, may be called opera.” Taubman writes that in a music column “it is not considered bad manners to discuss opera,” but he agrees with Loesser’s disclaimer. For Taubman, “

The Most Happy Fella

is not an opera.”

Times have changed. Thirty-five years and one less-than-ecstatically received production (1979) later, Conrad Osborne, in an essay published several days before its 1991 New York City Opera debut, singled out

The Most Happy Fella

as one of three operatic musicals—the others were

Porgy and Bess

and

Street Scene

—that “have shown a particular durability of audience

appeal and a growing (if sometimes grudging) critical reputation.”

39

Like his predecessors in 1956 Osborne observed “a tension between ‘serious’ musicodramatic devices and others derived from musical comedy or even vaudeville,” and noted perceptively that “this tension has been responsible for much equivocation about ‘Fella.’”

40

Rather than be disturbed by this clash between opera and Broadway, however, Osborne attributes “much of the fascination of the piece” to the same stylistic discrepancies that proved so disconcerting to Atkinson and Taubman.

41

Osborne also praises “Loesser’s melodic genius,” his “ability to send his characters’ voices aloft in passionate, memorable song that will take hold of anyone,” and contends that among musicals

The Most Happy Fella

ranks as “one of the few to which return visits bring new discoveries and richer appreciation.”

42