Encyclopedia Brown and Dead Eagles (4 page)

Read Encyclopedia Brown and Dead Eagles Online

Authors: Donald J. Sobol

The bearded cook rushed to the telephone.

While the bearded cook rushed to a telephone, the rest of the customers rushed for the door. No one wanted to get involved.

Within three minutes Officer Carlson drove up in a patrol car. Encyclopedia and Sally followed him to a large table in the rear.

Seated around the table were the only persons remaining in the restaurant: the bearded cook, two waitresses, Mario himself, and a dark-haired young woman with a bruise on her jaw.

They all started chattering at the sight of Officer Carlson. He had trouble quieting them. It was a while before he was able to piece together what had happened.

Every Tuesday Mario had the cash from the business put in the bank. The dark-haired young woman was his daughter, Isabel. As it was Tuesday, she had started for the bank with the money in an envelope in her purse. She never got there.

“I stopped in the ladies’ room to freshen my makeup,” she said. “I heard the door open behind me. The only thing I ever saw was a fist.”

A waitress had discovered her on the floor, unconscious. Her pocketbook lay open. The envelope with the money was gone.

Officer Carlson said, “Who knew about the weekly trips to the bank?”

“Everyone here,” answered Mario, a short, friendly man. “But I trust them all.... Wait! John Rizzo knew. He was my cook. I fired him last week.”

“Did you see him today?” asked Officer Carlson.

“No,” said Mario heavily.

Officer Carlson looked around. “The door to the ladies’ room can be seen from any of the tables,” he said. “So the thief knew when Isabel entered it.”

“The thief can’t be a woman,” said Mario. “No woman could knock out my Isabel with one punch. Isabel can carry a fifty-pound sack of flour under each arm. She is very, very strong.”

“And the thief can’t be a man,” said Officer Carlson. “A man certainly would have caused an outcry going into the ladies’ room. He wouldn’t have risked it.”

“So who does that leave?” exclaimed Mario.

“John Rizzo,” said Sally.

“You know him?” said Mario in surprise.

“No,” said Sally. “But you said that he knew about the weekly trips to the bank.”

“I don’t see how you can decide that John Rizzo is the thief,” said Encyclopedia.

“That’s because you are a boy,” answered Sally. “And boys today haven’t learned their manners.”

WHAT HAD SALLY SEEN?

(Turn to page 91 for the solution to The Case of the Mysterious Thief.)

The Case of the Old Calendars

Sally brought the news when she returned from lunch. “Butch Mulligan is in a fight at his house!”

Butch Mulligan was eighteen. His neck measured eighteen inches—around, not high. His arms looked as if they were made of steel cables.

“Who’s dumb enough to fight Butch?” asked Encyclopedia.

“Bugs Meany and his Tigers,” answered Sally gleefully.

“Hot dog!” exclaimed Encyclopedia and rushed for his bike.

A crowd of neighborhood children watched the action

and urged the Tigers to keep on fighting.

and urged the Tigers to keep on fighting.

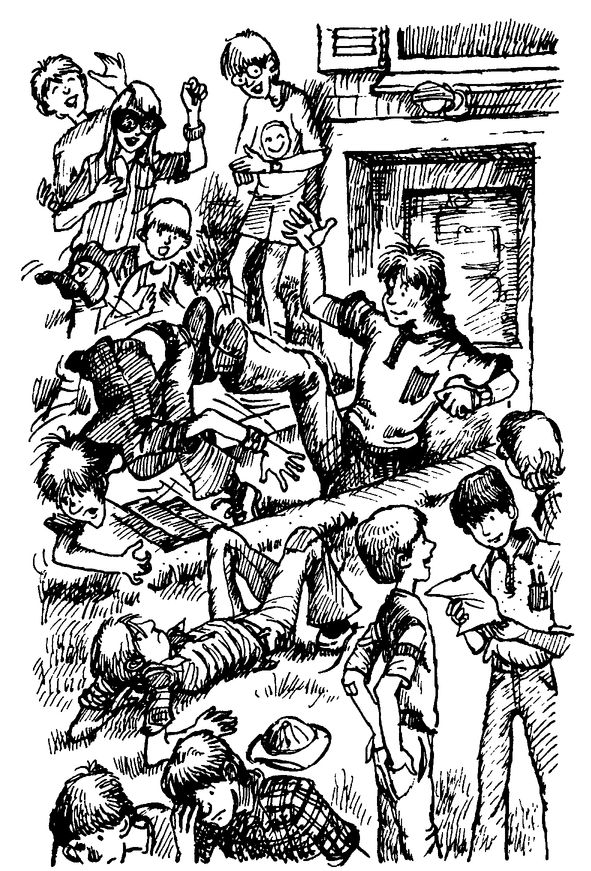

Butch lived on Suncrest Drive. When the detectives rode up, he was defending the steps that led down to the basement at the side of his house.

A crowd of neighborhood children watched the action and urged the Tigers to keep on fighting. Whenever a Tiger was sent whistling through the air, the children egged him on with cries of “More! More!”

As the detectives joined the crowd, two Tigers pulled themselves off the grass. They muttered to each other and charged Butch.

A swift kick in the shin greeted the first Tiger. He yelped, hopped backward, and fell to the ground.

“You kick them, and you don’t hurt your hands,” Butch explained to the crowd.

“Far out!” cried Millie Davis.

The second Tiger hissed, snorted, and leaped. He struck Butch with his shoulder and they both slipped to the bottom step. Butch recovered quickly. He pinned the Tiger’s arm and carried him back upstairs.

“I don’t mind the stairs,” Butch announced. “They keep the legs in shape.”

“Butch, you’re beautiful!” hollered Tim Shaw. “You can do it all!”

Everyone in the crowd cheered except Encyclopedia. He was trying to learn how the battle had started.

He finally spied Haystacks Mulligan, Butch’s little brother, in the back of the crowd. “What’s going on?” the detective inquired.

“Bugs tried to cheat Butch out of a calendar,” said Haystacks.

He explained that Mr. Downing, the math teacher, had moved to Michigan yesterday. Before he left, he had given twenty-five old wall calendars to Butch.

“Each calendar has a big picture of a Civil War battle on it,” said Haystacks. “They’re really neat!”

“How does Bugs figure in?” asked Encyclopedia.

“Bugs says he had asked for the calendars last week, but Mr. Downing forgot. So, according to Bugs, Mr. Downing gave him a note yesterday morning before he left Idaville. The note instructs Butch to give half the calendars to Bugs.”

Haystacks drew a slip of paper from his pocket and passed it to Encyclopedia. It read:

Dear Butch:

I forgot that I promised the calendars to Bugs Meany. Therefore, so that you may each have the same number, please divide the 25 calendars by

½.

½.

]ohn Downing

Haystacks said, “An hour ago Bugs showed up with the note. Butch took him to the basement and divided the twenty-five calendars. He kept twelve and gave Bugs twelve. That left one calendar.”

“Cutting it in half wouldn’t have been right,” said Encyclopedia.

“They decided to toss a coin for it,” said Haystacks. “Butch called heads. Bugs flipped a nickel and slapped it onto his wrist.”

“Bugs said it landed tails,” guessed Encyclopedia. “And Butch never got a chance to see for himself.”

“You’re right as rain,” said Haystacks. “Butch became disgusted. He threw Bugs and his twelve calendars out the basement door.”

Haystacks paused to watch a Tiger sail off Butch’s foot.

Then he continued. “Bugs screamed that nobody gets away with cheating him. He told his Tigers to gang up on Butch and teach him a lesson.”

“Somebody’s getting a lesson, all right,” said Encyclopedia.

A Tiger had jumped down behind Butch, where he suddenly realized he had no help. Butch went for him, grabbed his ankles and dragged him upstairs, bumpety-bump.

“When the head bangs on the steps, the brain thinks twice,” Butch said.

He flung the Tiger beneath a tree, and Dave Fine whooped. “That makes twenty-one!” Dave was keeping count of the knockdowns.

“Butch is drawing close,” said Nick Har mon. Nick’s hobby was world records. “Last year a saloonkeeper in England threw out eight drunks twenty-two times.”

“Butch can’t break that record,” insisted Ken Wilson, who would argue with an echo. “The Englishman handled the real goods. These are kids. They’re pretty skinny.”

“Yes, but they’re mean,” said Marcia Smith. “And remember the steps. Butch is working uphill.”

Bugs and Rocky Graham, the only two Tigers able to walk, wobbled toward Butch.

The crowd stilled. Everyone sensed a record in the making. It was like following a no-hitter into the ninth inning.

Butch broke the record as Sally reached Encyclopedia’s side. “Whatever made Butch so angry?” she gasped.

“If you think he’s angry now,” said Encyclopedia, “wait till he learns how Bugs tricked him!”

WHAT DID ENCYCLOPEDIA MEAN?

(Turn to page 92 for the solution to The Case of the Old Calendars.)

The Case of Lightfoot Louie

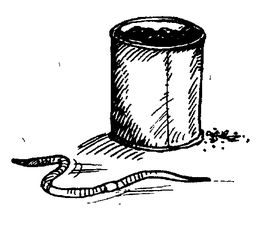

The state worm-racing championship was only two days off when Thad Dixon entered the Brown Detective Agency. He was walking.

Encyclopedia was very surprised to see an upright Thad. When the worm-racing season began, Thad usually went about on his hands and knees, searching for fast steppers.

“Gosh, Thad,” said Encyclopedia. “I didn’t expect to see you till after the big race. I thought you’d be using every minute to get Sis-Boom-Bah in shape.”

Sis-Boom-Bah was Thad’s wonder worm. The slim, five-inch athlete had fairly coasted to victory in the area trials a week ago.

Thad bowed his head. “Last Monday Sis-Boom-Bah went to that big mud hole in the sky,” he said sadly. “I stepped on him by mistake.”

“How awful,” exclaimed Sally.

Thad dug into his pocket for a quarter.

“I want to hire you,” he said. “I have to judge a worm today.”

He explained. With Sis-Boom-Bah dead, a lot of boys and girls had seen the chance to win the state championship.

To handle the rush of late entries, the Worm Racers’ Club of America had ruled that any club member could clock a worm’s speed. If fast enough, the worm would be allowed to enter the statewide race.

“I’m the club’s man in Idaville,” said Thad proudly. “So far this week I’ve turned down six worms and okayed one. Today I have to time Hoager Dempsey’s racer Lightfoot Louie.”

“What is Hoager doing training worms?” asked Sally. “He hates animals.”

“The owner of the winning worm gets a hundred-dollar savings bond this year,” said Thad. “If I don’t pass Lightfoot Louie, Hoager will get mad. He might even clap me on the ears with my own ankles. So I want you along.”

Before Encyclopedia could talk his way out of the case, Sally had accepted it. She had never liked Hoager, who was twelve and mean for his age.

Half an hour later, Thad cleared his throat as he stood in Hoager’s backyard. “We’ve come to time Lightfoot Louie,” he said. “Shall we begin?”

“You’re the boss, worm man,” replied Hoager.

He dragged over an outdoor table. On it he placed a clear plastic tube a foot long and an inch wide. One end was closed by a wad of paper.

“The tube makes a perfect racecourse, don’t you agree?” said Hoager, showing his teeth.

“Er... y-yes,” stammered Thad, and hastily he explained the rules. There was only one.

To qualify for the championship race, a worm had to travel five feet at a speed no slower than six hundred hours per mile.

“Lightfoot Louie can beat that waltzing,” bragged Hoager. He drew the worm from his pocket and slid him in the open end of the tube.

“Runner ready,” observed Thad, clearing his stopwatch. “On your mark ... get set... go!”

It wasn’t go. It wasn’t slow. It wasn’t anything. Lightfoot Louie didn’t move. He lay there like a wet shoelace.

“There’s too much sunlight,” said Hoager. “He’s sleepy.”

Hoager wrapped an old towel around the tube, hiding the racecourse completely. Next he shoved Lightfoot Louie farther into the tube. As soon as the worm disappeared, Hoager shouted, “What a start!”

Other books

150 Reasons Why Barack Obama Is the Worst President in History by Margolis, Matt, Noonan, Mark

All the Wrong Moves by Merline Lovelace

Let's Make It Legal by Patricia Kay

Island of Echoes by Roman Gitlarz

Ball of Fire by Stefan Kanfer

Blood Tears by Michael J. Malone

32 colmillos by David Wellington

Forbidden Love by Natalie Hancock

The Shorter Wisden 2013 by John Wisden, Co

The Faerie Prince (Creepy Hollow, #2) by Morgan, Rachel