End Procrastination Now! (19 page)

Read End Procrastination Now! Online

Authors: William D. Knaus

Different people have different goals, values, philosophies, and spiritual interests. So, if you want to follow the path of Siddhartha to a higher spiritual state, then the world of commerce and achievement is not your cup of tea. Thus, you probably won't gain from a to-do list. You already know what you want to accomplish, and awareness and experience are your guide.

If you value improving your work performances, you are likely to operate with a value of self-development and improvement. The products you produce become the by-products of this process. So, you will rarely get far in any campaign to overcome procrastination unless you take steps to go beyond the phase of an enlightened awareness about the procrastination currents in your life. You have to get in the boat and row if you want to contest the currents and get to a more productive place.

The following sections give you behavioral steps for getting past diversionary processes and getting to and accomplishing more of what it is in your enlightened interest to do. Each action presents choices to reduce procrastination and use this reduction to gain a greater benefit. Is choice important? Choice appears to be correlated with increases in production and reductions in procrastination.

Playing the role of a psychologist in a brief Mad TV sketch, comedian Bob Newhart had the same solution for every harmful habit: “

Stop it.

” Does this “stop-it” approach apply to procrastination? Newhart was making a joke. But this can be a serious solution if it is used as a thought-stopping exercise.

Thought stopping is an accepted behavior therapy practice that can sometimes have a quick and a favorable result. Internally shout

stop

when you recognize an automatic procrastination decision (APD). For example, you hear yourself say, “Later.” Immediately you internally shout, “

Stop it

.” You have little to lose by testing a behavioral thought-stopping exercise. However, plan to engage in what you'd ordinarily put off following shouting down an APD.

A

to-do list

is a catalog of items that you want to remind yourself to do. Using this organizing format, you may list items in their order of importance. The list may be a series of reminders, such as pick up the dry cleaning, get a gallon of milk, and call for a dental appointment. Some lists are templates for items that you routinely repeat: you want to remind yourself to stick to what it is important to do each day.

To-do lists can be short: one to five items. Short lists are useful when it is important to keep focused on a few important items. Throwing everything you can think of to do onto the list may be unrealistic, and you might bite off more than you can chew.

You can find different to-do list designs online. Some of them may be worth duplicating. You also can create your own list online and refer to it when you turn on your computer.

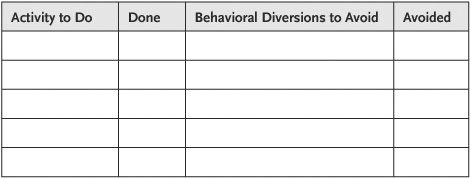

Your to-do list can combine items to do and behavioral diversions to avoid. Here is a sample form for you to complete:

Check off to-do items when they are done. This gives you a reference for your accomplishments. Check off behavioral diversions that you avoided. You make a gain each time you extract a procrastination keystone from a productive process and prevent this form of interference.

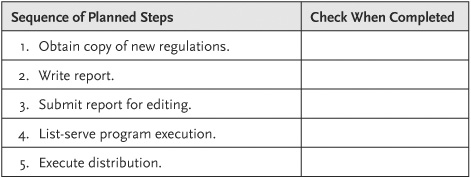

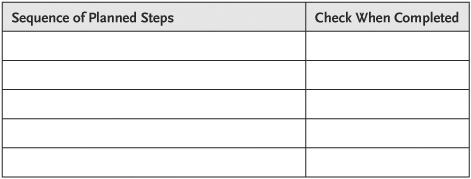

The cross-off planning sheet is a to-do list with a different twist. On the cross-off planning list, you cite the goal and list the steps. Then you cross off the steps as you complete them. Crossing off completed items can feel rewarding. Here is an example followed by a form for you:

Goal: Distribute information on a

change in federal regulation.

Goal:

In backward planning, you imagine that it is a year from today and you are looking back over a very productive period. I'll use physical exercise as an example to show how this planning sequence works.

From this imaginary future point in time, trace back how you accomplished a priority goal to engage in physical exercise three times a week for 45 minutes a session. In working backward, you can say:

5. I worked out for a year, and I am in great shape and feel energetic.

4. I continued with my schedule, and I refused to cut myself any slack.

3. Before that, I entered the gym for the first time and began the program.

2. Before that, I phoned the fitness center and set up an appointment.

1. Before that, I accepted a feeling of discomfort as part of the process of going from where I am to where I'd like to be, and I stubbornly refused to substitute diversion for purposeful accomplishments.

Since the backward plan ends with the first step, you know where to start.

Backward planning has value when you visualize a result, but you rarely think about the steps that lead to the accomplishment. If you can visualize an outcome, then is it possible for you to visualize the step that came before meeting a long-term goal? Devising a plan is an important step in the process of changing from a behavioral diversion habit pattern to a productive pattern. Without preparation, you are vulnerable to a

promissory note

style of procrastination. Your plan helps you over the threshold from wishing to doing. However, you get the actual payoff when you execute the plan and persist with what you started. Once you have made the conceptual effort to go an extra step, it is simpler and easier to take concrete behavioral steps in the direction of your goal.

Organization systems do not, by themselves, curb procrastination. Nevertheless, these mechanical techniques can be part of a solution for operating with higher levels of efficiency and less stress caused by lost materials and shifting from activity to activity without finishing any of them (

rotating door procrastination style

). If you don't have a workable organizing system and you view yourself as not well organized, consider creating an organizing system to establish control over your routine. Here are some tips for building organization and efficiency into your routine:

1. Schedule time for recurring events (paying bills, cleaning, automobile oil changes, and so on), and follow the schedule.

2. Set aside a location for putting important objects in their place (keys, reading materials, bills).

3. Eliminate time-hog activities that consume a great deal of time but that yield little return (toss mail and e-mail advertisements and other materials with little relevance).

4. Delegate: hire someone to clean and take care of activities that cost you more to do than to farm out.

5. When feasible, order items online and have them delivered.

6. Schedule time for matters that require concentration when you are least likely to be interrupted.

7. If you are inclined to “forget” certain items nested within your system, use a reminder system. An elastic band on your wrist can serve as a reminder.

8. Avoid overorganizing or overscheduling your activities.

Behavioral procrastination can follow the development of an organizing system: you gather the information and set the system in place, then don't use it. Sometimes you have to push yourself to the next level of efficiency to get past a behavioral procrastination barrier. However, if you continue to bog down with this form of stop-start approach, ask yourself what you think is the underlying cause. Ask what you can do to move forward.

When you talk yourself through the paces, you give yourself verbal instructions about what you'll do first, what you'll do second, and so forth: Now I will spell out my goal in concrete and measurable terms. Now I will lay out a plan to achieve the goal. Now I will take the first step in the plan. Now I will take the second step in the plan, and so on. Now I will review what happened and decide on adjustments. These instructions are covert, such as silently talking to yourself.

Using covert self-instruction accomplishes several results. You act to stop behavioral diversions. You substitute a proactive learning process for a procrastination process. You start sooner and finish faster. You benefit from improved performance.

Self-instruction may apply to improving sports performances. Sports psychologists John Malouff and Coleen Murphy found that

golfers can improve their scores by giving themselves a self-instruction of their choice, such as “body stiff before each putt.” Self-instruction also helps impulsive kids improve their school performances.

The most complex challenges have a simple beginning. A person with a Ph.D. degree in theoretical physics started with simple steps in that direction. In a nutshell, the idea is to break it down and keep it simple.

You can break any complex task into a first step and manageable parts. Pretend that you are a project manager, and you need to break down a task for others to perform. What are the first, second, third, and subsequent steps? What instructions would you give to execute the first step?

Now, switch gears. Give yourself instructions, such as, “First I'm going to do this: _________. Next, I'll _________.” Take the first step, and follow it up with a second.

Simplify the steps. The first step can be as straightforward as dialing a number for a phone call, booting your computer, opening a book, or getting out a pen and paper.

Consistently use the five-minute plan to introduce a change to disrupt a procrastination habit process. First, commit yourself to taking five minutes to get started. After those five minutes, decide whether to commit yourself for another five minutes. You continue deciding at five-minute intervals (or another interval that works for you) until you decide to stop. When you are ready to quit, take a few added minutes to prepare for your next work session.

The five-minute system can be a surprisingly effective way to start intermediate- and longer-term projects. However, what if you put off the first five minutes? Regroup. Ask yourself what makes

the task seem worthy of avoiding now. What are you doing to stop yourself from starting? The answers can point to a more basic problem that needs to be solved.

Tad couldn't get himself started on preparing an argument for a court presentation. The legal issues were complex. He was to face off against a senior partner from a large and successful law firm. Tad felt intimidated.

We talked about his anxiety about having his arguments torn apart in court. And since he was not yet clear on his arguments, Tad had to admit that he had no way of knowing whether he would be outgunned until he understood the issues.

The five-minute approach helped save the day. Tad agreed to take the five-minute approach to read the materials from von Clausewitz on preparation and how preparation can shape decisions. Five minutes wasn't such a long time.

Once Tad got the picture from me and from von Clausewitz's work, he applied the five-minute principle to gather information, research the law, and ask for help from other counsel. On the day of the trial, the high-powered lawyer that he had feared walked out of the court with egg on his face. Tad's argument was compelling and grounded. The judge complimented him on his superior preparation. Tad is a great fan of the five-minute plan. He calls it his friendly ally.