Financial Markets Operations Management (53 page)

Read Financial Markets Operations Management Online

Authors: Keith Dickinson

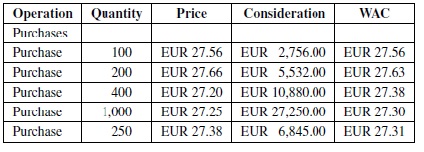

In the previous section, the gain or loss calculation for Jardine Cycle & Carriage was straightforward as there was only one purchase and one sale. It becomes slightly more complicated when you have a security which is actively traded, with several purchases and sales. In the following example you will see there are several purchases followed by one sale; the question here will be how much gain or loss has the sale made?

There are three approaches to this, and each gives a different answer:

- First In, First Out (FIFO):

The sale price is compared with the price of the first purchase. - Last In, First Out (LIFO):

The sale price is compared with the price of the last purchase. - Weighted Average Cost (WAC):

The sale price is compared with the average weighted cost of all the previous purchases.

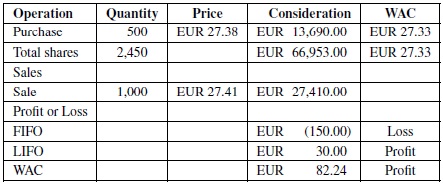

You will see in

Figure 13.9

that there are several purchases and one sale in the shares of French supermarket company, Carrefour SA (CA:PAR).

FIGURE 13.9

Transactions in Carrefour shares

The sale of 1,000 shares at a price of EUR 27.41 per share generates sale proceeds of EUR 27,410.00. Depending on the calculation convention adopted, the amount of profit or loss differs:

- FIFO:

There is a loss of EUR 150.00, as the first purchase was at a higher price of EUR 27.56 per share; - LIFO:

There is a profit of EUR 30.00, as the most recent purchase was at EUR 27.38 per share; - WAC:

There is also a profit of EUR 82.24 per share.

We therefore have a situation where, depending on which calculation convention we adopt, there are three different profit/loss outcomes. The question is: which of these three is correct? The answer is that all three are correct. You might therefore be tempted to choose the one convention that suits your situation at any particular time; for example, you might choose the WAC if you wanted to maximise your profit or FIFO if you wanted to reduce your tax liability. However, one of the accounting profession's concepts and conventions is concerned with consistency. You would be expected to be consistent in the accounting treatment of items such as Profit & Loss calculations; if you start by using WAC, then you should continue in the same way.

Realised gains feed through to the Profit & Loss account as a credit and realised losses as a debit.

In much the same way that securities held in a trading book are initially measured at fair value (and any changes are recorded in income as they happen), derivative instruments are also measured at fair value.

The key difference between cash market securities and derivative instruments is that in the latter we expect to either pay or receive any gains/losses as they occur. Why should this be the case? To answer this, you need to appreciate what is perhaps the main distinction between securities and derivatives. In the case of securities, you are expected to settle the transaction

both in full and within a short period after the original trade date; settling the transaction eliminates the original counterparty risk between buyer and seller.

With derivatives, however, you may (or may not) be expected to pay the full economic cash value of the underlying derivative asset until some future date. The amount of time could be several weeks or months or years after the trade date and this exposes one counterparty to the risk of default of the other counterparty. By paying or receiving the change in the daily mark-to-market valuation, both counterparties reduce their economic exposures to each other on an overnight basis rather than intra-period.

We will take a look at how exchange-traded derivatives (ETDs) and OTC derivatives are treated in the next two sections. Please be aware that the situation on the OTC side is fundamentally changing due to pressure from industry regulators. We will look at this later in the section.

You will recall from a previous chapter that once an ETD transaction has been executed, both trading counterparties register their trades with a clearing house. Once the clearing house has matched the buyer's and seller's information, it becomes the counterparty to the buyer and separately the counterparty to the seller (novation). This means that should either the buyer or the seller default, it becomes the clearing house's responsibility to manage the subsequent un-winding of the position. Clearly, this puts the clearing house in a potentially risky situation, especially in a crisis situation where several counterparties are defaulting. For this reason, the clearing house has to have a robust risk-management system, and part of the risk mitigation is to request margin from counterparties that clear through the clearing house. Margin can be paid either in cash or in eligible non-cash assets such as high-grade treasury bonds, corporate bonds and money-market instruments.

The term

margin

therefore refers to the changes in fair value, payable or receivable by a counterparty to/from the clearing house. For any ETD product it is the clearing house that specifies how much margin is payable and what the deadlines are for its payment.

There are two variants of margin: initial margin and variation margin.

This represents a returnable deposit by the clearing member to the clearing house and is an amount based on the risk profile of the contract. The purpose of initial margin is to allow the clearing house to hold sufficient funds on behalf of each clearing member to offset any losses incurred between the last payment of margin and the close out of the clearing member's positions should the clearing member default. Initial margin is usually calculated by taking the worst probable loss that the position could sustain over a fixed amount of time, and can be paid in either cash or non-cash collateral. Initial margin is a Balance Sheet item.

Traditionally, each and every open contract would have been margined as a separate exercise. Today, most clearing houses have adopted the process of collating similar derivative contracts into a “portfolio”, stress testing the portfolio and calculating one amount of margin. The original framework, known as Standard Portfolio Analysis of Risk (SPAN), was developed by the Chicago Mercantile Exchange and subsequently licensed to a number of other international clearing houses. This one-stop-shop approach provides for a more accurate netting of risk and a more efficient use of collateral.

This represents the profits or losses on open positions which are calculated daily in the mark-to-market process and then paid or collected. Variation margin is usually calculated at the end of each business day by the clearing house, and then settled the next business day. Unlike initial margin, which is kept by the clearing house until a position is closed out or reaches expiry, variation margin is collected from the loss-making side of the contract by the clearing house, and then paid to the profit-making side of the contract. Variation margin is a Profit & Loss account item.

As an example of how initial and variation margin work, let us take a look at the traditional methodology using an index futures contract, the FTSE 100 Index Future (see

Figure 13.10

).

| Contract Specification | ||

| FTSE 100 Index Futures | ||

| Trading code â Z | Market â NYSE LIFFE London | Product type â Index future |

| Unit of trading | Contract valued at GBP 10 per index point (e.g. value GBP 66,000 at 6600.0) | |

| Quotation | Index points (e.g. 6600.0) | Â |

| Tick size/Value | 0.5/GBP 5.00 | Â |

| Delivery months | March, June, September, December (nearest four available for trading) | |

| Contract standard | Cash settlement based on the exchange delivery settlement price (EDSP) |

Source:

NYSE LIFFE (online) Available from

https://globalderivatives.nyx.com/en/products/index- futures/Z-DLON/contract-specification.

[Accessed Monday, 18 November 2013]

FIGURE 13.10

Index futures contract

Our transaction details are shown in

Table 13.13

.

TABLE 13.13

Transaction details

| Details | Â | Price |

| Delivery month: | December 2013 contract | Â |

| Transaction: | Investor buys (to open) 10 contracts @ | 6,712.00 |

| Trade date: | Day 1 | Â |

| Contract size: | GBP 10.00 | per contract |

| Initial margin: | GBP 1,000.00 | per contract |

| FTSE 100 Index on Day 1 | 6703.50 | Â |

| FTSE 100 Index on Day 2 | 6666.50 | Â |

| FTSE 100 Index on Day 3 | 6683.00 | Â |

| Day 4 | Investor sells (to close) 10 contracts @ | 6,715.50 |

We can see here that the transaction was profitable overall (we opened at 6,712.00 and closed at 6,715.50). Notice, though, that the transaction was losing money by the end of Day 1, as the contract closed lower at 6,703.50. The next two tables will show the daily mark-to-market prices plus the impact on initial margin and variation margin (see

Table 13.14

) and the accounting treatment of the cash items (see

Table 13.15

).

TABLE 13.14

Margin calculations

| Â | Â | Â | Â | EOD | Initial | Variation | Pay/ |

| Date | Direction | Contracts | Price | Price | Margin | Margin | Receive |

| Day 1 | Buy | 10 | 6,712.00 | Â | GBP (10,000.00) | Â | Pay |

| Â | CFWD | 10 | Â | 6,703.50 | Â | GBP (850.00) | Pay |

| Day 2 | BDWN | 10 | 6,703.50 | Â | Â | Â | Â |

| Â | CFWD | 10 | Â | 6,666.50 | Â | GBP (3,700.00) | Pay |

| Day 3 | BDWN | 10 | 6,666.50 | Â | Â | Â | Â |

| Â | CFWD | 10 | Â | 6,683.00 | Â | GBP 1,650.00 | Receive |

| Day 4 | BDWN | 10 | 6,683.00 | Â | Â | Â | Â |

| Â | Sell | 10 | Â | 6,715.50 | GBP 10,000.00 | GBP 3,250.00 | Receive |

| Â | Â | Â | Â | Â | GBP Â Â Â Â Â 0.00 | GBP Â Â 350.00 | Â |

| Overall P/L | GBP 350.00 | Profit | Â | Â | Â | Â | Â |

TABLE 13.15

Accounting entries

| Date | Details | DR | CR | Comments |

| Day 1 | Initial margin on futures | GBP 10,000.00 | Â | Balance Sheet asset |

| Â | Variation margin on futures | GBP Â Â Â 850.00 | Â | P & L account |

| Â | Bank | Â | GBP 10,850.00 | Balance Sheet asset |

| Day 2 | Variation margin on futures | GBPÂ Â 3,700.00 | Â | P & L account |

| Â | Bank | Â | GBP Â Â 3,700.00 | Balance Sheet asset |

| Day 3 | Variation margin on futures | Â | GBP Â Â 1,650.00 | P & L account |

| Â | Bank | GBPÂ Â 1,650.00 | Â | Balance Sheet asset |

| Day 4 | Initial margin on futures | Â | GBP 10,000.00 | Balance Sheet asset |

| Â | Variation margin on futures | Â | GBP Â Â 3,250.00 | P & L account |

| Â | Bank | GBP 13,250.00 | Â | Balance Sheet asset |

| Â | Reconciliation | DR | CR | Balance |

| Totals: | Initial margin on futures | GBP 10,000.00 | GBP 10,000.00 | GBPÂ Â Â Â Â 0.00 |

| Â | Variation margin on futures | GBPÂ Â 4,550.00 | GBP Â Â 4,900.00 | GBPÂ Â 350.00 |

| Â | Bank | GBP 14,900.00 | GBP 14,550.00 | GBP (350.00) |

In the centrally cleared world of ETD transactions, margin is one element in the clearing house's risk mitigation. With the notable exception of SwapClear (launched in 1999 by LCH.Clearnet), OTC derivative contracts are not generally cleared centrally. It is the responsibility of the buyer and the seller to make suitable arrangements to mitigate the counterparty risk exposures.

It is usual to revalue an OTC contract on a daily basis (in much the same way as in the centrally cleared environment), and an amount of collateral representing the value of the contract will be delivered by the counterparty with the exposure to the counterparty with the risk. This is very much a bilateral activity, but formalised under agreements produced by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA). The main agreement types

2

include the following:

- ISDA Master Agreement;

- ISDA Credit Support Documentation;

- ISDA Definitions;

- Regulatory documentation.

According to the ISDA's 2014 Margin Survey (published in April 2014), 91% of all cleared and non-cleared OTC derivatives trades were subject to collateral agreements, of which 87% were ISDA agreements.

3

In order to be able to calculate the correct amount of collateral, it is necessary to value the contracts. This would be straightforward if prices were available centrally, for example, through an exchange or a clearing house. However, due to the bilateral nature of OTC derivatives trading, there is no central pricing facility. Instead, market participants have to use a range of pricing systems and models in order to establish a fair price. It is quite possible for the counterparties to the same trade to have different revaluation prices.

It is intended that by 2014 all non-cleared OTC derivative contracts will be cleared through a clearing house. For their part, clearing houses will, theoretically, become comfortable clearing OTC derivative contracts on condition that they (a) understand the contracts and (b) are able to revalue them. Hence, SwapClear clears a range of vanilla interest rate swaps.

4

SwapClear revalues clearing member positions daily using zero-coupon yield curves which are published and made available to the members. This is one of the key features of the service and ensures the independence of the valuation process.