Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition (28 page)

Authors: Howard Schilit,Jeremy Perler

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Accounting & Finance, #Nonfiction, #Reference, #Mathematics, #Management

First, here are the two basic rules:

(1)

rather than keeping costs on the Balance Sheet too long (i.e., EM Shenanigan No. 4), rush them to the trash bin of expenses immediately, and

(2)

instead of trying to hide expenses by failing to record invoices (i.e., EM Shenanigan No. 5), record them all now (the earlier the better) and then some—even if you literally make up expenses just for the heck of it

Sounds crazy, no? Stay tuned, and soon you will fully understand how management benefits from playing this game—and companies play it more frequently than you would imagine.

This chapter highlights two general techniques that management uses to shift future-period expenses into earlier periods.

Techniques to Shift Future Expenses to an Earlier Period

1. Improperly Writing Off Assets in the Current Period to Avoid Expenses in a Future Period

2. Improperly Recording Charges to Establish Reserves Used to Reduce Future Expenses

1. Improperly Writing Off Assets in the Current Period to Avoid Expenses in a Future Period

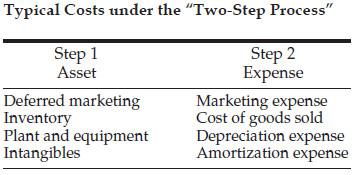

Let’s briefly return to our Texas two-step dance for assets to expenses. When it is done right, step 1 requires placing costs on the Balance Sheet as assets, since they represent future long-term benefits. Step 2 involves shifting those costs to the proverbial trash bin (known as expenses) when the benefits are received. Chapter 6, “EM Shenanigan No. 4,” showed the first way to bungle the two-step—by shifting from step 1 to step 2 far too

slowly

, or perhaps not at all. This chapter shows another inappropriate way to dance the two-step that is actually the opposite of the dance discussed in Chapter 6—simply shift costs from step 1 to step 2

immediately

. In other words, write off assets by recording expenses

much earlier

than is warranted .

Improperly Writing Off Deferred Marketing Costs

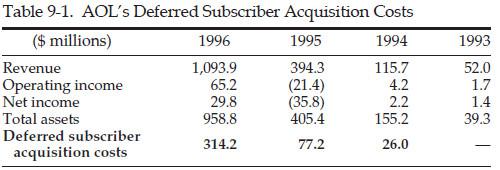

You may recall that when we last saw our friends at AOL in Chapter 6, they were struggling to show a profit and had begun capitalizing marketing and solicitation costs in order to push the company into the black. We roundly criticized them for inflating profits by capitalizing normal expenses on the Balance Sheet. We then censured them for stretching out the amortization period for these costs from one to two years; this further muted the expenses and inflated profits. So, where we left the story a few chapters ago, AOL had accumulated more than $314 million in the asset account labeled

deferred subscriber acquisition costs (DSAC).

(See Table 9-1.) But the company still had a big problem: those costs represented tomorrow’s expense, and they would need to be amortized over the next eight quarters—a $40 million hit to earnings each quarter. Considering AOL’s modest earnings level ($65.2 million in operating income in fiscal 1996), a recurring $40 million quarterly charge would be, to put it mildly, quite unwelcome.

So, three months later, when its DSAC asset had ballooned to $385 million, AOL shifted to Plan B and started playing its version of the

opposite game

. Rather than continuing with the two-step dance and amortizing the marketing costs over the next eight quarters, AOL switched gears and announced “a one-time charge” to write off the entire amount in one fell swoop. Of course, it had to come up with a justification to convince the auditors that this asset account had suddenly become “impaired” and would provide no future benefit. So AOL stated that the write-off was necessary to reflect changes in its evolving business model, including reduced reliance on subscribers’ fees as the company developed other revenue sources. To say that we were skeptical of this explanation would be an understatement.

Just to be clear about the brazenness and extent of the company’s scheme, let’s recap. First, AOL decided to push normal solicitation costs onto the Balance Sheet to give investors the impression of being a profitable company, when in reality the company was very unprofitable and was burning through a ton of cash. Second, it stretched out the one-year amortization period to two years, further inflating profits by cutting the amortization expense recorded each quarter in half. Of course, at this point, the company knew that it still had a very big challenge. By using aggressive accounting practices, it had successfully pushed more than $300 million of expenses into the future; however, it had failed to make these expenses disappear forever. But not to worry, the AOL magicians still had one more trick up their sleeve—the grand finale. In an illusion for the ages, management used a $385 million charge to eliminate all these looming expenses and downplayed the significance by simply calling it a “change in accounting estimate.” Surely you agree that these actions are the product of major

chutzpah

.

Improperly Writing Off Inventory as Being Obsolete

Unlike the solicitation costs that AOL had improperly capitalized for years (before it started playing the opposite game), inventory costs most certainly should be capitalized and then later expensed either when the product is sold (most of the time) or when it is written off as obsolete (less frequently). The most common shenanigans with inventory accounting involve failing to shift costs from the asset account to expense in a timely manner. This trick naturally would understate expenses and inflate profits. Since we are playing the opposite game here, though, let’s assume that management decides to write off the inventory cost as an expense long before any sale takes place.

Cisco Systems Writes Off Billions in Inventory.

During the technology bust in 2000, many companies properly wrote off impaired assets, including inventory, plant and equipment, and intangibles. Cisco System Inc.’s $2.25 billion inventory write-off in April 2001, however, stood out from the pack as unusual. This inventory charge seemed massive in isolation, but upon closer inspection and compared with the most recent quarter’s cost of goods sold, we really understood the magnitude of that number: the amount written off represented more than 100 percent of that entire quarter’s inventory sales. Wow!

Why are we getting so excited? Turn the clock ahead a quarter or two to when the economy started to improve and Cisco’s revenue returned to normal levels. Assuming that Cisco chose not to throw all of those written-off routers in the trash when taking the onetime charge (probably a pretty safe assumption), the company then would have reported sales with an inflated profit margin. To illustrate, here are some simple numbers: Cisco spends $100 to manufacture inventory, and then sells it for $150, producing a $50 gross profit (33.3 percent margin). If, during that earlier period, the $100 unit had been written off to zero and subsequently sold for $150, Cisco would recognize a $150 profit (100 percent margin). Or even if it had just written down the inventory to $75, Cisco would recognize a $75 profit (50 percent margin). There is no clear-cut evidence that Cisco ever sold and reported huge profit margins on units that had been written off or even partially written down. There is reason to be suspicious, however, given

(1)

company comments on its earnings call suggesting that it would not be scrapping all of the written-off inventory and

(2)

the rapid expansion in gross margin in subsequent periods

Too Many Toys.

Toys ‘R’ Us accumulated excess inventory that it failed to sell. The company announced that it would take a $396.6 million (pretax) restructuring charge to cover the cost of a “strategic inventory repositioning” (interpretation: it simply moved slow-selling inventory off of its shelves), as well as the closing of stores and distribution centers. In a report to investors at the time, the Center for Financial Research and Analysis (CFRA) warned that Toys ‘R’ Us might have bundled into the charge normal operating costs that would otherwise have been included as operating expenses in future periods. The portion of the charge related to repositioning of inventory amounted to $184 million. The company explained that the inventory was removed from the stores and sold at lower prices through alternative distribution channels. Normally, the inventory would be written down to its net realizable value and the difference charged as an operating expense.

Whether we are considering AOL’s acceleration of deferred marketing costs, Cisco’s writing off of inventory that it did not throw away, or Toys ‘R’ Us’ taking large one-time charges, each seemingly had the same ultimate result: accelerating future-period expense into the current period and, moreover, categorizing the write-off as being unrelated to normal activities and showing it below the line. Such actions inflate future-period profits with no detriment to current-period operating results.

Accounting Capsule: Restructuring Charges Create Interperiod and Intraperiod Benefits

EM Shenanigan No. 7 creates both interperiod and intraperiod benefits for management. First, future-period expenses are accelerated to an earlier period, leaving fewer expenses to burden the later one. Second, the accelerated expenses are often classified as “restructuring” or “one-time charges” and presented below the line, creating a win-win situation for the company: operating income (above the line) in the period of the charge is unaffected, since the impact is felt below the line; and operating income in the later period is inflated, as some normal expenses have been pulled out and included in the earlier-period charge.

Improperly Writing Off Plant and Equipment Considered Impaired

When we introduced shenanigans involving plant and equipment in Chapter 6, we cautioned about management reporting inflated profits by depreciating these assets over too long a period or failing to write them off completely if their value becomes permanently impaired. As we continue the opposite game, let’s shift gears and think how management can accelerate current-period expenses by curtailing the depreciation period and announcing impairment charges for certain pieces of plant and equipment, even though they may be perfectly fine. Investors should be particularly alert to this type of shenanigan when it corresponds to the hiring of a new CEO with tantalizing stock options or if management uses this ploy with uncommon regularity.

Lesson One for New CEOs.

Do you ever wonder how a person prepares to take the reins as CEO of a public company? Surely, seminars abound, along with books and other training material. No doubt, one of the lessons taught would be what to do in the first 90 days on the job. Considering how often such a scenario plays out, we would not be surprised if the following strategy was found as Lesson One in the “New CEO Playbook.”

During your first few weeks on the job, announce some bold initiatives to clean up the mess left by your predecessor and try to look like a strong, decisive leader with a solid grip on the details. Oh, and be sure to announce a streamlining of operations and a large write-down of assets (often called a “big bath”)—the larger the write-down, the better. Investors will be impressed, and, of course, it makes showing earnings growth in future periods infinitely easier; you just lowered the bar by shifting those future expenses into today’s charge. Include in your announcement the need to write off bloated inventory and plant assets. Investors won’t even penalize the company for the near-term loss, since it will all be packaged below the line. When tomorrow comes, you will report much improved profits, since many of tomorrow’s costs have already been written off as part of the special charge.