Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students (103 page)

Read Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students Online

Authors: Louise Lewis

BOOK: Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students

5.14Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

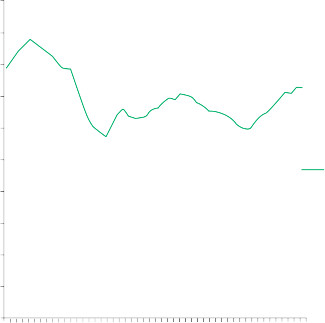

241

1,000,000

900,000

800,000

700,000

600,000

242

500,000

400,000

300,000

200,000

100,000

1960

1963

1966

1969

1972

1975

1978

1981

1984

1987

1990

1993

1996

1999

2002

2005

2008

2011

0

Number of live births

Figure 11.4

Graph showing number of live births in the England and Wales over a 50-year period (between 1961 and 2011) (ONS, 2012c).

Table 11.1

Maternal and infant deaths

Measure

Definition

Stillbirth

Since 1992: a child born from the 24th completed week of gestation, who never showed any signs of life.

Stillbirth rate

Number of stillbirths per 1000 total births (live births plus stillbirths).

Early neonatal deaths

Deaths under seven days.

Perinatal deaths

Stillbirths and early neonatal deaths.

Maternal mortality

The death of a woman within 42 days of the end of pregnancy from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes.

Maternal mortality rate

Number of maternal deaths of mothers, from direct and indirect causes, within the first 42 days after the end of pregnancy per 100,000 maternities (pregnancies).

Maternal mortality ratio

Number of maternal deaths of mothers, from direct and indirect causes, within the first 42 days after the end of per 100,000 live births.

Neonatal deaths

Deaths under 28 days.

Post-neonatal deaths

Deaths between 28 days and 1 year.

Infant deaths

Deaths under 1 year.

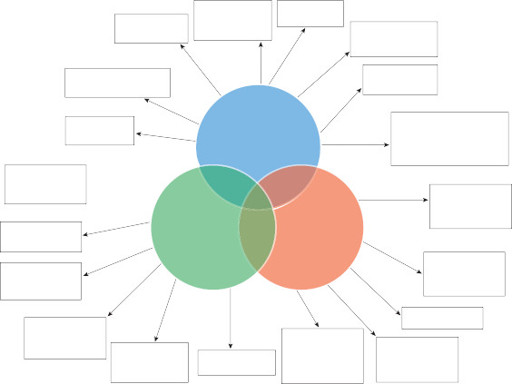

Domains of public health

The UK Faculty of Public Health (2010) has identified three interrelated domains of public health

(see Figure 11.5) (Griffiths et al. 2005). These are:

health improvement

health protection

health services (quality improvement).

Health improvement

concerns socioeconomic aspects, health promotion, and determinants of health (Thorpe et al. 2008). This encompasses reducing health inequalities in partnership with multiple sectors (Griffiths et al. 2005).

Health protection

includes the control of infectious and communicable diseases and environmental hazards; strategies include immunisation pro- grammes (Thain and Hickman 2004).

Health service (quality improvement)

relates to the role of healthcare systems, service planning and quality, clinical effectiveness, clinical governance and health economics. These include prioritisation and equity of services, clinical audit, evaluation and research (Thorpe et al. 2008; UK’s Faculty of Public Health 2010).

243

243

HealthEducationHousingFamily/communityinequalities

HealthEducationHousingFamily/communityinequalities

Health

promotion EmploymentLifestyles

Health improvement

Surveillance and monitoring of disease and risk factorsClinical effectivenessEfficiencyService planning

Improving (health) services

Health protection

Infectious diseasesChemicals and poisonsAudit and evaluationsClinical governanceEquityEnvironmental health hazardsRadiationEmergency response

Figure 11.5

Diagram illustrating the three domains of public health and the scope of public health practice.244

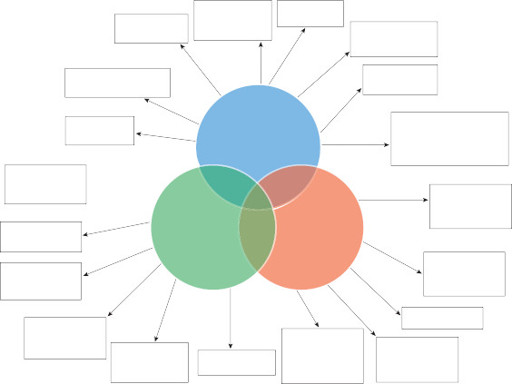

Health improvement: the midwife and health promotion

Health promotion is defined as activities designed to maintain optimum health and quality oflife for groups of people; these involve engaging the community in their personal health whether individually or collectively (Martin 2010). Childbirth, as a normal life event, fits within a health promotion framework (Beldon and Crozier 2005). Health education uses persuasive methods to inform groups or individuals about adopting healthier lifestyles and rejecting unhealthy habits; the educator determines what changes will be beneficial for the population (Martin 2010). Piper (2005) proposes four categories of health promotion strategies used by midwives; these are the

behaviour change agent

, the

collective empowerment facilitator

,

strategic practitioner

and

collective empowerment

facilitator (see Figure 11.6).

The

The

behaviour change agent

, or

health persuasion

approach uses health education where an expert clinician (e.g. midwife) identifies areas within the medical model of health requiring change in the recipients of care (Piper 2005). Disease prevention is emphasised, using orthodox medical approaches (Furber 2000; Whitehead 2003). Pregnancy is seen as the pre-eminent ‘

teachable moment

’ (Herzig et al. 2006, p. 230): women are highly motivated and responsive, within a context of relatively intensive and continuous care from health professionals. Preventa- tive measures may be

primary, secondary

or

tertiary

, these relate respectively to avoidance of disease (or wider public health problems), control of an identified condition, or preventing worsening of an identified issue.An

empowerment facilitator

uses non-coercive, democratic, women-centred methods to achieve health promotion through constructive partnership with women (e.g. in the use of the

Objective knowledge emphasis

Midwife as expert and midwife focussed intervention

The midwife as behaviour change agent

The midwife as strategic practitioner

Individual woman focus

Women (population) focus

The midwife as empowerment facilitator

The midwife as collective empowerment facilitator

Subjective knowledge emphasis

Women as experts and women focused intervention

Figure 11.6

Diagram displaying the difference between models of health promotion (Piper 2005).expert patient, patient advice, liaison services and engagement of service users (Piper 2005). A

strategic practitioner

uses the legislative action to evaluate wider socio-political issues which affect the health of individuals, but are beyond their direct control. These include, health in- equalities and unequal distribution of wealth and capital (Furber 2000; Piper 2005). This is a top-down approach to health promotion. The

collective empowerment facilitator

employs the ‘community development method’ of health promotion (Furber 2000; Piper 2005), focusing on societal factors as the main determinant of health. However, these operate a bottom-up approach, responding to the collectively expressed, subjective health needs of women and their families. Examples include the facilitation of peer support schemes for mothers, such as breast- feeding drop-in peer support groups (Piper 2005).

Health surveillance

Health surveillance aims to, ‘

provide the right information, at the right time, in the right place to

inform decision-making and action-taking

’ (DH 2013a, p. 5). Screening is part of health surveil- lance which is part of routine antenatal midwifery care. Screening is where apparently healthy members of a population are assessed for their susceptibility to diseases and conditions (Tiran 2008; Martin 2010). Antenatal screening may include determining a mother’s carrier status for recessive genetic disorders, which the baby could inherit or the mother’s susceptibility to certain infectious diseases. UK childbearing women are offered a programme of routine antenatal screening and diagnostic testing in pregnancy for certain infectious diseases in the mother, which may be at a pre-clinical stage, but still infectious (Tiran 2008; Porth 2009; Martin 2010). Additional screening and diagnostic testing are made available when there is a clear history of exposure or susceptibility. This programme aims to improve health outcomes in the population of childbearing women and their babies (see Chapter 6: ‘Antenatal midwifery care’, where ante- natal screening is discussed in greater depth).

Improving health services through clinical audit: confidential enquiries into maternal and child health

A major way in which clinical audit has been used to inform maternal public health is the Con-fidential Enquiries into maternal deaths instituted in the UK in 1952 and subsequently infant mortality (Weindling 2003; Kee 2005). These gather statistical data on maternal and infant mor- tality over a three year period (e.g. Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries (CMACE) 2011). These enquiries revealed key areas of risk, compelling midwives to act to reduce maternal mortality in relation to key issues including:

Health improvement

concerns socioeconomic aspects, health promotion, and determinants of health (Thorpe et al. 2008). This encompasses reducing health inequalities in partnership with multiple sectors (Griffiths et al. 2005).

Health protection

includes the control of infectious and communicable diseases and environmental hazards; strategies include immunisation pro- grammes (Thain and Hickman 2004).

Health service (quality improvement)

relates to the role of healthcare systems, service planning and quality, clinical effectiveness, clinical governance and health economics. These include prioritisation and equity of services, clinical audit, evaluation and research (Thorpe et al. 2008; UK’s Faculty of Public Health 2010).

243

243 HealthEducationHousingFamily/communityinequalities

HealthEducationHousingFamily/communityinequalitiesHealth

promotion EmploymentLifestyles

Health improvement

Surveillance and monitoring of disease and risk factorsClinical effectivenessEfficiencyService planning

Improving (health) services

Health protection

Infectious diseasesChemicals and poisonsAudit and evaluationsClinical governanceEquityEnvironmental health hazardsRadiationEmergency response

Figure 11.5

Diagram illustrating the three domains of public health and the scope of public health practice.244

Health improvement: the midwife and health promotion

Health promotion is defined as activities designed to maintain optimum health and quality oflife for groups of people; these involve engaging the community in their personal health whether individually or collectively (Martin 2010). Childbirth, as a normal life event, fits within a health promotion framework (Beldon and Crozier 2005). Health education uses persuasive methods to inform groups or individuals about adopting healthier lifestyles and rejecting unhealthy habits; the educator determines what changes will be beneficial for the population (Martin 2010). Piper (2005) proposes four categories of health promotion strategies used by midwives; these are the

behaviour change agent

, the

collective empowerment facilitator

,

strategic practitioner

and

collective empowerment

facilitator (see Figure 11.6).

The

Thebehaviour change agent

, or

health persuasion

approach uses health education where an expert clinician (e.g. midwife) identifies areas within the medical model of health requiring change in the recipients of care (Piper 2005). Disease prevention is emphasised, using orthodox medical approaches (Furber 2000; Whitehead 2003). Pregnancy is seen as the pre-eminent ‘

teachable moment

’ (Herzig et al. 2006, p. 230): women are highly motivated and responsive, within a context of relatively intensive and continuous care from health professionals. Preventa- tive measures may be

primary, secondary

or

tertiary

, these relate respectively to avoidance of disease (or wider public health problems), control of an identified condition, or preventing worsening of an identified issue.An

empowerment facilitator

uses non-coercive, democratic, women-centred methods to achieve health promotion through constructive partnership with women (e.g. in the use of the

Objective knowledge emphasis

Midwife as expert and midwife focussed intervention

The midwife as behaviour change agent

The midwife as strategic practitioner

Individual woman focus

Women (population) focus

The midwife as empowerment facilitator

The midwife as collective empowerment facilitator

Subjective knowledge emphasis

Women as experts and women focused intervention

Figure 11.6

Diagram displaying the difference between models of health promotion (Piper 2005).expert patient, patient advice, liaison services and engagement of service users (Piper 2005). A

strategic practitioner

uses the legislative action to evaluate wider socio-political issues which affect the health of individuals, but are beyond their direct control. These include, health in- equalities and unequal distribution of wealth and capital (Furber 2000; Piper 2005). This is a top-down approach to health promotion. The

collective empowerment facilitator

employs the ‘community development method’ of health promotion (Furber 2000; Piper 2005), focusing on societal factors as the main determinant of health. However, these operate a bottom-up approach, responding to the collectively expressed, subjective health needs of women and their families. Examples include the facilitation of peer support schemes for mothers, such as breast- feeding drop-in peer support groups (Piper 2005).

Health surveillance

Health surveillance aims to, ‘

provide the right information, at the right time, in the right place to

inform decision-making and action-taking

’ (DH 2013a, p. 5). Screening is part of health surveil- lance which is part of routine antenatal midwifery care. Screening is where apparently healthy members of a population are assessed for their susceptibility to diseases and conditions (Tiran 2008; Martin 2010). Antenatal screening may include determining a mother’s carrier status for recessive genetic disorders, which the baby could inherit or the mother’s susceptibility to certain infectious diseases. UK childbearing women are offered a programme of routine antenatal screening and diagnostic testing in pregnancy for certain infectious diseases in the mother, which may be at a pre-clinical stage, but still infectious (Tiran 2008; Porth 2009; Martin 2010). Additional screening and diagnostic testing are made available when there is a clear history of exposure or susceptibility. This programme aims to improve health outcomes in the population of childbearing women and their babies (see Chapter 6: ‘Antenatal midwifery care’, where ante- natal screening is discussed in greater depth).

Improving health services through clinical audit: confidential enquiries into maternal and child health

A major way in which clinical audit has been used to inform maternal public health is the Con-fidential Enquiries into maternal deaths instituted in the UK in 1952 and subsequently infant mortality (Weindling 2003; Kee 2005). These gather statistical data on maternal and infant mor- tality over a three year period (e.g. Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries (CMACE) 2011). These enquiries revealed key areas of risk, compelling midwives to act to reduce maternal mortality in relation to key issues including:

Other books

Operation Napoleon by Arnaldur Indriðason

Towards a Dark Horizon by Maureen Reynolds

Shifters by Lee, Edward

A Potion to Die For: A Magic Potion Mystery by Blake, Heather

The Marriage Bed (The Medieval Knights Series) by Dain, Claudia

Hybrid: Savannah by Ruth D. Kerce

All in the Family by Taft Sowder

Wired for Culture: Origins of the Human Social Mind by Mark Pagel

The Pearl Savage by Tamara Rose Blodgett

Snapshot by Angie Stanton