Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students (107 page)

Read Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students Online

Authors: Louise Lewis

BOOK: Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students

3.73Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Facial dysmorphia

Facial dysmorphiaFetal alcohol spectrum disorders

Growth deficiencyCentral nervous system abnormalitiesPremature birthReduced head circumferenceNeurological problems

255

255Figure 11.14

Diagram listing the characteristics associated with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

Alcohol consumption

Discussions about alcohol consumption in pregnancy are complex. As with smoking, drinking alcohol is legal and may be perceived as more culturally acceptable (pre and post-conception). Regular, moderate to heavy alcohol consumption in pregnancy is associated with neural, cranial and facial abnormalities seen in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (Hutson et al. 2012; see Figure 11.14). Alcohol mimics the endocrine effects of maternal stress on the maternal hypothalamic– pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, leading to fetal growth restriction, underdevelopment and immu- nosuppression (Goldsmith 2004). The impact of these is chronic and irreversible. Since fetal alcohol spectrum disorders are entirely preventable, by abstinence, it is ethically problematic to conduct prospective studies to determine safe limits of alcohol consumption (Goldsmith 2004; Green 2007). Pregnant women and women planning to become pregnant should be advised to avoid drinking alcohol in the first three months of pregnancy, because there may be an increased risk of miscarriage (RCOG 2006).

Non-abstinent pregnant women should drink no more than one–two UK units once or twice a week, since there is no evidence of harm to their unborn baby, at these levels (NICE 2008).

Women should be advised not to get drunk or binge drink (drinking more than 7.5 UK unitsof alcohol on a single occasion) while they are pregnant because this can harm their unborn babies (NICE 2008).However, the RCOG (2006) recommends total alcohol abstinence to avoid any risks to the pregnancy.

Illicit substances

Childbearing women may use opiates such as heroin which is snorted, smoked or injected. Its effects are to stimulate opiate receptors causing drowsiness and euphoria, but also nausea and respiratory depression (Hussein Rassool and Villar-Luís 2006). Heroin is physically addictive;256users experience increasing tolerance. People using heroin eventually require higher doses to experience the same effect. Withdrawal symptoms are experienced. Heroin crosses the placenta like many other psychoactive substances and in common with other opiates causes neurobe- havioural teratogenicity. Maternal heroin use is associated with the following:

Illicit substances

Childbearing women may use opiates such as heroin which is snorted, smoked or injected. Its effects are to stimulate opiate receptors causing drowsiness and euphoria, but also nausea and respiratory depression (Hussein Rassool and Villar-Luís 2006). Heroin is physically addictive;256users experience increasing tolerance. People using heroin eventually require higher doses to experience the same effect. Withdrawal symptoms are experienced. Heroin crosses the placenta like many other psychoactive substances and in common with other opiates causes neurobe- havioural teratogenicity. Maternal heroin use is associated with the following:

Neonatal abstinence syndrome, including:

irritability

tremors

hypertonicity

tachypnoea

vomiting

diarrhoea. (Hussein Rassool & Villar-Luís 2006)

Injecting drug use also increases women’s risk of contracting blood-borne viruses such as hepatitis B and C and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (Ornoy and Tenenbaum 2006; Thorne and Newell 2008; Sargent and Clayton 2010). Stimulants like cocaine provide increased energy and confidence, but have well-known physical effects such as tachycardia, hypertension and tachypnoea. Side effects include myocardial infarction (MI), cerebrovascular accident (CVA), seizures, depression, paranoia and venous injury. Due to its expense and illegality, cocaine has links to criminal behaviour. Its effects on the fetus and neonate are not well-established because the harmful effects cannot easily be isolated from those caused by concurrent aspects of health inequality like poverty, teenage pregnancy, single parenthood and common co-morbid factors such as: alcohol, tobacco, amphetamine and opiate abuse (Hussein Rassool and Villar-Luís 2006). Cannabis, or marijuana has also been reported to have negative consequences on the fetus, but no robust study has been conducted. There are numerous newer recreational or street drugs becoming available. Women seldom experience substance misuse in isolation from other complex social needs (NICE 2010). NICE (2010) recommends that all pregnant women be given lifestyle advice pertaining to smoking cessation, recreational drug use (implications) and alcohol consumption at the first contact with a health professional.

Domestic abuse

An area of increasing prominence in the maternal public health agenda is domestic abuse.

Domestic abuse is:

. . . any incident of threatening behaviour, violence or abuse (psychological, physical, sexual, financial or emotional) between adults who are or have been intimate partners, or family members; regardless of gender, sexuality, disability, race or religion . . .

(British Medical Association (BMA) (2007, p. 1)

The scale of the issue is significant, in that it is increasingly recognised as a major contributor to poorer maternal, fetal and neonatal health outcomes (Lewis 2007; CMACE 2011; Table 11.4). Women experiencing domestic abuse may demonstrate recognised patterns of behaviour (Department of Health [DH] 2005; Green and Ward 2010); these include late antenatal booking and poor attendance at antenatal appointments. They may present with repeated attendance in a minor injuries setting or have recurrent admissions with indefinable complaints, or unex- plained. These women may demonstrate non-compliance (with treatment and management of various conditions). They may present to clinicians with mental health issues such as depression, anxiety or self-harm. They may exhibit injuries that are untended and of different ages, which they try to conceal or minimise. Women may also present with sexually transmitted infections

Table 11.4

The scale of domestic abuse

28% of women aged 15–59 have experienced domestic abuse.

About 10,000 women per week per week are sexually assaulted.

About 2000 women per week are raped.

34% of all reported rapes are on children under 16.

16% of children experienced sexual abuse in childhood.

More than five million women during childhood experienced sexual abuse.

People with a limiting illness or disability are more likely to experience abuse.

(STIs), urinary tract infections (UTIs) and vaginal infections; they may also have signs of poor obstetric history (Department of Health (DH) 2005; Green and Ward 2010). Women may find it difficult to escape the scrutiny of an abusive partner or relation. Between 2006 and 2008, CMACE (2011) identified 39 maternal deaths (12%) as displaying features of domestic abuse, a fifth by an intimate partner. The Task Force on Violence against Women and Children (2010) called for a national public health campaign on violence against women and children. Routine enquiry about domestic violence is now established midwifery practice, increasing frequency of disclo- sure (DH 2005; Price et al. 2007). Opportunity is sought for the pregnant women to consult with the midwife alone, at least once, which has been found highly acceptable to childbearing women. Midwives however, need training and education to help them better support women (Baird et al. 2011).

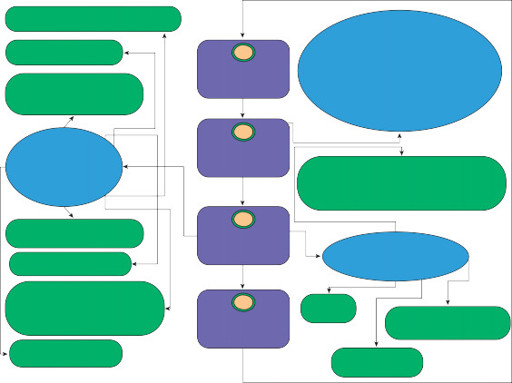

Midwives must promote the best interests of women and babies with complex social factors, through competent referrals (see Figure 11.15), providing appropriate advice, support and monitoring within the interprofessional team, and adopting a non-judgemental approach, making it possible for women to disclose their problems and complex social factors (NMC 2008; NICE 2010).

257

Activity 11.1

Think about how might you adapt the flow diagram in Figure 11.15 to help tackle the following

issues:

Smoking

Mental health problems (see Chapters 4 and 13)

Obesity

Teenage mothers (see Chapter 5)

Asylum seekers

Non-English speaking women

Domestic abuse

Conclusion

At some point, every baby had a mother; at some point every person was a baby. Therefore,midwives have a great responsibility and opportunity to support, and improve the health of the

Social workers/ social care teamMental health teamOther midwives involved in care of woman and baby1

Social workers/ social care teamMental health teamOther midwives involved in care of woman and baby1

Ask

Give and explain informationon evidence based consequences for mother and babies. Discuss the benefits of addressing issues affecting health

258To relevant health& social care professionalsObstetrician: Consultant led careGeneral Practitioner2

258To relevant health& social care professionalsObstetrician: Consultant led careGeneral Practitioner2

Inform

3

Refer

Give contact details for charities and supporting organisations (e.g. refuge, women’s aid, talk to frank)Support systems for the womanHealth visitors involved in care of woman and baby/ Family nurse partnershipSafeguarding team4

Review

DoulasProfessional and peer support servicesInterpretation services

Figure 11.15

Referral pathway for women with complex social needs.childbearing population and their babies. Any intervention aimed at reducing maternal and infant morbidity and mortality should be considered to be a major public health strategy. Mid- wifery care, as a whole could, therefore, be regarded as a public health intervention. It is recog- nised that there is a growing level of complexity in maternal and neonatal public healthcare. However midwives are strongly involved in delivering public healthcare.

Key points

Key points

Conclusion

At some point, every baby had a mother; at some point every person was a baby. Therefore,midwives have a great responsibility and opportunity to support, and improve the health of the

Social workers/ social care teamMental health teamOther midwives involved in care of woman and baby1

Social workers/ social care teamMental health teamOther midwives involved in care of woman and baby1Ask

Give and explain informationon evidence based consequences for mother and babies. Discuss the benefits of addressing issues affecting health

258To relevant health& social care professionalsObstetrician: Consultant led careGeneral Practitioner2

258To relevant health& social care professionalsObstetrician: Consultant led careGeneral Practitioner2Inform

3

Refer

Give contact details for charities and supporting organisations (e.g. refuge, women’s aid, talk to frank)Support systems for the womanHealth visitors involved in care of woman and baby/ Family nurse partnershipSafeguarding team4

Review

DoulasProfessional and peer support servicesInterpretation services

Figure 11.15

Referral pathway for women with complex social needs.childbearing population and their babies. Any intervention aimed at reducing maternal and infant morbidity and mortality should be considered to be a major public health strategy. Mid- wifery care, as a whole could, therefore, be regarded as a public health intervention. It is recog- nised that there is a growing level of complexity in maternal and neonatal public healthcare. However midwives are strongly involved in delivering public healthcare.

Key points

Key pointsOther books

London Large: Blood on the Streets by Robson, Roy, Robson, Garry

His Millionaire Maid by Coleen Kwan

Murder in Montmartre by Cara Black

Sid (The Protectors Series) Book #4 by Gabelman, Teresa

Relentless Pursuit by Donna Foote

The Baker Street Letters by Michael Robertson

An Improvised Life by Alan Arkin

Undercover Pursuit by Susan May Warren

Fugitive by Phillip Margolin

Surest Poison, The by Campbell, Chester D.