Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students (158 page)

Read Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students Online

Authors: Louise Lewis

BOOK: Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students

5.2Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

denial

anger

bargaining

depression

acceptance.There is an assumption that people move through the stages in order having completed one stage before going on to the next; however this is not so and the theory is criticised as being too linear and rigid. If it is taken more as a cycle that people move through in both directions at times, it is perhaps more helpful but it has to be accepted that some people never really reach acceptance. The loss of a baby, particularly by miscarriage or stillbirth, is something that some parents and their family do not fully accept and events or stressors can send them back through the stages almost from the beginning. Anecdotal evidence does suggest, however, that what happens following the loss can impact on the process of grief. Those who experienced perinatal loss in the past suffered from the lack of mementoes and limited emotional care, and this ulti- mately affected their ability to come to acceptance.Bowlby (1973) based his four stage model on his influential theory of attachment. Unlike Kübler-Ross his stages of grief are overlapping and flexible. They are:

shock

yearning and protest

despair

recovery.

There are clear similarities to Kübler-Ross’ stages with ‘yearning and protest’ having some link with the two stages of denial and anger, but the language does perhaps better fit with perinatal loss. Parents and families are frequently very shocked at their loss which they have very little if any time to prepare for (with the exception of some neonatal deaths and planned termination for major abnormality). The idea of yearning and protest has resonance with the loss of a baby as does despair. Recovery seems to be a better description of how many view their progress and is more suggestive of ‘getting on with life’ despite the loss. Parkes (1998) presented a theory which is very similar to Bowlby with four stages which are:

shock or numbness

yearning and pining

disorganisation and despair

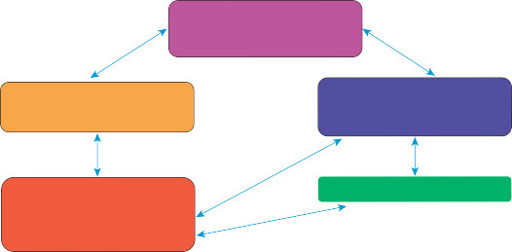

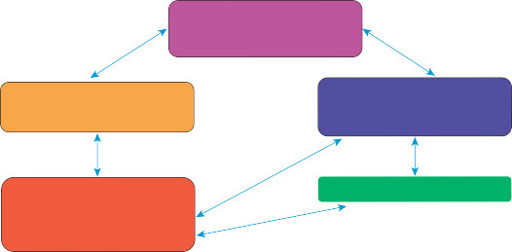

recovery.Again Parkes (1998) emphasised that the stages are not linear and could be experienced several times. A trigger for returning to earlier stages could be an anniversary (Parkes 1998) and this can be important when the date of birth is also the date of death as the anniversary is particularly poignant. A trigger for some women can also be a new pregnancy when the joy is mixed with anxiety and sadness for the baby they lost.Worden (1982, 1996) developed a non-linear and dynamic model which involves the bereaved person working to accept the loss and the pain and adjusting to the loss by ‘relocation of the deceased person in one’s life’ (1996, p.15). Again there are similarities to other models and an emphasis on recovery not being reliant on forgetting the person who has died, but rather coming to terms with their loss. It is important not to suggest that life will be the same as it was before the bereavement as this is not possible. Work by Rando (1985, 1986) on parental grief suggests that although the physical relationship may have been lost, the emotional bond is not. Worden (1982) suggested that part of the process of grief was adjusting to changes in role, identity and status associated with the loss of their loved one. Perinatal loss is associated with a significant change in role and identity, as parents and family expected to have a new baby to relate to so their expected role as mother, father, grandparent etc is no longer relevant in the context of the deceased baby. Rubin and Malkinson (1993) support this and suggest that par- enthood can enhance a person’s sense of identity and perinatal loss therefore involves a loss of self in relation to social roles.Dual-process models of coping with bereavement such as that of Stroebe (1998) suggest that people have to cope with both loss and restoration-oriented factors and they will oscillate between the two. Whilst loss-oriented processes link with the stages of grief expressed by other theorists, restoration-oriented processes are related to coping with everyday life and building new roles and relationships. Dual process models have been criticised for placing too much emphasis on coping (Buglass 2010), but they do recognise that both expressing and controlling feelings are part of grief. Parents and families can sometimes feel guilty about coping and being able to control their feelings and it is important that they are reassured that this is ‘normal’.The value of the theories of grief is not in expecting everyone to behave according to any one theory, but to help the midwife understand the possible stages women and their families may go through and to therefore understand that their behaviour is part of the process. It is also helpful when reassuring grieving individuals that they are not ‘going mad’ or behaving abnormally as they sometimes believe. Staged models (see Figure 17.1) for the most part help us understand that the process can move backwards as well as forwards through their grieving and the dual-process theory highlights that the process is not just about loss it is also about coping and adjusting to life without the baby and their expected future.

375

375

Denial ShockShock or numbnessAcceptance RecoveryAnger Yearning & protest Yearning & piningBargainingDepression Despair Disorganisation & Despair

Denial ShockShock or numbnessAcceptance RecoveryAnger Yearning & protest Yearning & piningBargainingDepression Despair Disorganisation & Despair

Figure 17.1

Summary of stages of grief models.

376

376

Communication

Communication underpins effective midwifery care whatever the situation, but communicatingin relation to breaking bad news and caring for bereaved women and their families is particu- larly challenging for many midwives. Walter (2010) suggests that practitioners need to be aware of their own assumptions about grief and loss and Schott and Henley (1996) state that there is a need for healthcare practitioners to understand their own style of communication before they can adapt to meet the needs of different people and situations. Walter’s (2010) suggestion is important as it reminds practitioners that their own assumptions can limit sensitivity to the needs of women and their families and can therefore lead to poor communication and care. Kohner and Henley (2009) highlight how, for example, professionals can wish to protect parents from the distress of their experience which ultimately results in poor communication. This desire to protect is based on assumption and a paternalistic approach to care that does not empower women and their families. However this does not mean that communication and care should not be sensitive and sympathetic to the distress women and their families will inevitably experi- ence, but it is important that midwives provide communication that best meets the needs of those in their care.Box 17.1 highlights the basic principles of good communication and these apply when break- ing bad news and caring for those who are grieving as much as they do in any other circum- stance. It is important that it is not assumed that first names should be used because someone is distressed for example, and even where this may be acceptable it is wise to check what name the person wishes to be known by (some people do not use their first name, may prefer or dislike shortened versions of their name and some cultures order their names differently). The use of jargon and colloquial language is also detrimental to understanding and can lead to frustration on the part of women and their families as they struggle to comprehend what they are being told. Assessing what is being understood by questioning and allowing a chance for concerns or queries to be expressed ensures that the process of communication is as effective as it can be given the circumstances. Inclusive communication is important as fathers and

Box 17.1 Basic principles of good communication

Box 17.1 Basic principles of good communication

375

375 Denial ShockShock or numbnessAcceptance RecoveryAnger Yearning & protest Yearning & piningBargainingDepression Despair Disorganisation & Despair

Denial ShockShock or numbnessAcceptance RecoveryAnger Yearning & protest Yearning & piningBargainingDepression Despair Disorganisation & DespairFigure 17.1

Summary of stages of grief models.

376

376Communication

Communication underpins effective midwifery care whatever the situation, but communicatingin relation to breaking bad news and caring for bereaved women and their families is particu- larly challenging for many midwives. Walter (2010) suggests that practitioners need to be aware of their own assumptions about grief and loss and Schott and Henley (1996) state that there is a need for healthcare practitioners to understand their own style of communication before they can adapt to meet the needs of different people and situations. Walter’s (2010) suggestion is important as it reminds practitioners that their own assumptions can limit sensitivity to the needs of women and their families and can therefore lead to poor communication and care. Kohner and Henley (2009) highlight how, for example, professionals can wish to protect parents from the distress of their experience which ultimately results in poor communication. This desire to protect is based on assumption and a paternalistic approach to care that does not empower women and their families. However this does not mean that communication and care should not be sensitive and sympathetic to the distress women and their families will inevitably experi- ence, but it is important that midwives provide communication that best meets the needs of those in their care.Box 17.1 highlights the basic principles of good communication and these apply when break- ing bad news and caring for those who are grieving as much as they do in any other circum- stance. It is important that it is not assumed that first names should be used because someone is distressed for example, and even where this may be acceptable it is wise to check what name the person wishes to be known by (some people do not use their first name, may prefer or dislike shortened versions of their name and some cultures order their names differently). The use of jargon and colloquial language is also detrimental to understanding and can lead to frustration on the part of women and their families as they struggle to comprehend what they are being told. Assessing what is being understood by questioning and allowing a chance for concerns or queries to be expressed ensures that the process of communication is as effective as it can be given the circumstances. Inclusive communication is important as fathers and

Box 17.1 Basic principles of good communication

Box 17.1 Basic principles of good communicationGood manners – respect and courtesy, introduce yourself and find out how others wish to be addressed.

Communicating to meet clients’ needs – avoid jargon and colloquial language, assess knowl-edge and understanding.

Encourage questions and expression of concerns or worries.

Be non-judgmental and inclusive.

REMEMBER TO LISTEN AS WELL AS TALK.grandparents can feel excluded and feel that the focus of both communication and care is on the woman when they also need to understand and be cared for, to enable them to care for each other. An understanding of the theory of grief and loss can help midwives deal with the responses women and their families may make to their bereavement and thereby enhance the non-judgmental approach.Research by Nordlund et al. (2012) highlights the need to show respect to the baby within communication. Describing the baby as ‘the miscarriage’, ‘the fetus’ or ‘it’ was perceived as being very hurtful and offensive. The research also demonstrated that the respondents felt that a lack of respect for their circumstances was shown by professionals who talked about irrelevant topics and who were too upbeat. Another interesting comment from a respondent highlighted how she felt upset that some professionals were seen by her to be hugging and supporting one another in a way they had not provided support to her. This latter finding highlights the problem of whether it is appropriate and professional to show emotion in relation to their loss. The comment would imply that it is acceptable to cry with the woman and her family when that emotion is about their experience, but professional behaviour would be to keep personal feel- ings for later as much as possible. The research also demonstrates that non-verbal communica- tion is also important to women and their families. Respondents reported lack of eye contact from professionals which they found distressing. See Box 17.2 for principles of sensitive communication.As with all aspects of care communication in relation to bad news and care following bereave- ment needs to take into account cultural need and language barriers. Interpreters and taped/ written information should be utilised to minimise language barriers so that no-one is denied access to the information and support they are entitled to.

Culture and religion

There is much information available within healthcare about cultural and religious beliefs relat-ing to grief and mourning rituals and whilst this information is undoubtedly useful it is also very generalised. Walter (2010) makes the important point that although individuals are shaped by their culture they are not ‘determined by it’ and similarly religion and culture interact with one another. There may be a tension between what the individual wants and what their culture requires them to do and if healthcare professionals merely use the cultural information available to shape their communication and the choices offered they may not be fully meeting the indi- viduals’ needs at best and at worst they may be contributing to the tension experienced. The

377

377

Box 17.2 Principles of sensitive communication

Box 17.2 Principles of sensitive communication

Culture and religion

There is much information available within healthcare about cultural and religious beliefs relat-ing to grief and mourning rituals and whilst this information is undoubtedly useful it is also very generalised. Walter (2010) makes the important point that although individuals are shaped by their culture they are not ‘determined by it’ and similarly religion and culture interact with one another. There may be a tension between what the individual wants and what their culture requires them to do and if healthcare professionals merely use the cultural information available to shape their communication and the choices offered they may not be fully meeting the indi- viduals’ needs at best and at worst they may be contributing to the tension experienced. The

377

377 Box 17.2 Principles of sensitive communication

Box 17.2 Principles of sensitive communicationOther books

Curtis by Kathi S. Barton

Zombie Versus Fairy Featuring Albinos by James Marshall

The Passion Play by Hart, Amelia

Accord of Mars (Accord Series Book 2) by Kevin McLaughlin

Loss by Tony Black

El caballo y su niño by C.S. Lewis

The Marching Season by Daniel Silva

Then You Hide by Roxanne St. Claire

Edge of Valor by John J. Gobbell

Nothing by Blake Butler