Garbology: Our Dirty Love Affair With Trash (3 page)

Read Garbology: Our Dirty Love Affair With Trash Online

Authors: Edward Humes

Tags: #Travel, #General, #Technology & Engineering, #Environmental, #Waste Management, #Social Science, #Sociology

40 billion plastic knives, forks and spoons

4.5 million tons of office paper

Enough aluminum to rebuild the entire commercial air fleet four times over

Enough steel to level and restore Manhattan

Enough wood to heat 50 million homes for twenty years

Enough plastic film to shrink-wrap Texas

Plastic waste is so plentiful and so carelessly treated that 92 percent of Americans have potentially harmful plastic chemicals in their urine

10 percent of the world oil supply is used to make and transport disposable plastics

Growing, shipping and selling food destined to be thrown away uses more energy than is currently produced by offshore oil drilling

No less than 28 billion pounds of food thrown away, about 25 percent of the American food supply, perhaps more by some estimates

PART

1

THE BIGGEST THING WE MAKE

Our willingness to part with something before it is completely worn out is a phenomenon noticeable in no other society in history … It must be further nurtured even though it runs contrary to one of the oldest inbred laws of humanity, the law of thrift.

—

J. GORDON LIPPINCOTT, 1947

A society in which consumption has to be artificially stimulated in order to keep production going is a society founded on trash and waste, and such a society is a house built upon sand.

—

DOROTHY L. SAYERS, 1947

Who steals my purse steals trash.

—

IAGO, IN SHAKESPEARE’S

Othello

1

AIN’T NO MOUNTAIN HIGH ENOUGH

M

IKE

S

PEISER’S SCULPTING TECHNIQUE IS A STUDY

in geometric perfection and economy of motion. Every cut, every shave, every subtle drag of his blade has a purpose, each forming a small piece of a much larger work, sprawling and unique.

His peers call him Big Mike, for he is a mountain of a man, shaved head set like an amiable boulder atop broad shoulders and a mighty belly, six-two and more than three hundred pounds. He seems designed by central casting exactly for the purpose of wielding his main artistic tool—the towering, thundering 60-ton BOMAG Compactor. With its roaring, clanking assistance, Big Mike has helped build something unprecedented: the Puente Hills landfill, largest active municipal dump in the country.

Puente Hills is so sprawling that it has evolved its own ecosystem and nature preserve, spawned multiple community organizations formed to kill it, and holds enough strata of methane-spewing decomposing garbage to power a hundred thousand homes (which is exactly what is done with the eye-watering “landfill gas” bubbling up from beneath). Puente Hills has been the final resting place for the lion’s share of Los Angeles County’s ample daily flow of garbage for more than three decades—130 million tons of it and counting.

One hundred thirty million tons: Such a number is hard to grasp. Here’s one way to picture it: If Puente Hills were an elephant burial ground, its tonnage would represent about 15 million deceased pachyderms—equivalent to every living elephant on earth, times twenty. If it were an automobile burial ground, it could hold every car produced in America for the past fifteen years.

It is, quite literally, a mountain of garbage.

Big Mike’s German-made BOMAG is the primary tool for taming this garbage nexus. The BOMAG (derived from the German-language mouthful of a company name, Bopparder Maschinenbau-Gesellschaft) is a fourteen-foot-tall, thirty-foot-long, swivel-hipped bulldozer that can turn on a dime yet push its terrain-clearing blade with 100,000 pounds of force. Its six-foot wheels are spiked with dinosaur-sized steel teeth that can crush, mold and squeeze up to 13,000 tons of garbage into a fifteen-foot-deep rectangle the length and width of a football field.

Big Mike sculpts such a mound not in a month or a week, but in one glorious day, every day, as he and his colleagues dump, push, carve and build a pinnacle of trash where once there were canyons. He is king of a mountain built of old tricycles and bent board games, yellowed newspapers and bulging plastic bags, sewage sludge and construction debris—all the detritus, discards and once valuable tokens of modern life and wealth, reduced to an amorphous, dense amalgam known as “fill.”

The football-field-sized plot at the center of activity atop Puente Hills is called a “cell,” not in the prison-block sense, but more akin to the tiny biological unit, many thousands of which are needed to create a single, whole organism. As with living creatures, this cell, titanic as it is, represents a small building block for the modern landfill—the part that grows and reproduces each day. A dozen BOMAGs, bulldozers and graders swarm over this fresh fill every day, backing and turning and mashing and shaping, their warning gongs clanging and engines roaring in a controlled chaos, mammoth bees crawling atop the hive. Their curved steel blades raise up and blot the sun, then drop into the sea of trash and push it forward, waves of debris flowing off either side as if the dozers’ blades were the prows of a schooner fleet, complete with the flap and quarrel of seagulls overhead, their cranky squawks drowned out by the diesel din. A sickly-sweet smell of decay kicks up when the cell is churned this way, and the thrum and grind of the big engines can be felt in the ground near the cell. The noise induces sympathetic vibrations in the chest of anyone nearby, creating the uncomfortable sensation of being near a marching band with too many bass drummers.

Building a garbage mountain is difficult, edgy, dangerous work. Within the new cell, the trash flow can pile up twenty to thirty feet or more during the day before it’s crushed and compacted and covered with clean dirt (that’s what makes it a

sanitary

landfill—the ick gets buried every day). The drivers negotiating and moving that cell-in-the-making must constantly be wary of the drop-off from their garbage pile—and the uncontrolled, possibly tumbling sled ride that tipping over the edge could bring about. Eight landfill workers nationwide died on the job in 2010.

To build a proper trash mountain, one that is a feat of engineering rather than a random aggregation of garbage, each cell must be level at the top so it can be covered and sealed with up to a foot of soil, the last task of any day at the landfill. The machine operators rely on laser-guided markers to keep their mound level, except for Big Mike, who seems to be able to do it by dead reckoning alone. His coworkers say he can visualize the final form of a field of compacted trash the way an artist can see the carving within the block of wood or the figure hiding inside the marble. A member of Puente Hills’s team of waste engineers, guys with hard hats and clipboards who plot out each day of garbage burial with the same care and planning once lavished on an Egyptian mummy’s tomb, glances one morning at a section of new fill and says, “Oh, look at that perfect edge—that’s Big Mike’s work. That’s his style.” The other engineers nod.

Later, Mike grins sheepishly when he hears about the compliment. He’s forty-eight and has been doing this for twenty years. The little fang earrings he sports jiggle a little with his chuckle. “I do love my work,” he says. “Where else can you accomplish something every day, see the progress right in front of you, and know you’re doing something useful and good? And on top of that, it’s fun. Where else are you going to drive a hundred and twenty thousand pounds of machine around all day and get paid for doing it?”

His life’s work is the mother of all landfills, its innovations and pioneering techniques copied and studied. But in truth, calling it a landfill these days is a bit misleading, as it stopped physically “filling” a depression in the land (the original definition of landfill) long ago. For quite some time, the garbage mountain of Puente Hills has been rising above its surrounding terrain, resembling nothing more than a huge and eerily modern version of an ancient tell—those giant mounds in the Middle Eastern deserts that mark where once-mighty cities rose and fell, and that now lie buried and broken beneath the sands.

Archaeologists love tells—and, particularly, the middens they usually conceal, those ancient trash dumps that, five thousand years later, provide a treasure trove of information about life and events in the distant past. Archaeologists long ago figured out that the real nature of human life isn’t that we are what we eat. They know we are best understood by what we throw away. Thousands of years from now, the Puente Hills landfill, buffered, insulated, wrapped in layers of clay and polyethylene, and more secure against earthquakes, winds and floods than any other structure in California, may serve a similar archaeological purpose, a tell for future researchers hoping to puzzle out our lifestyle, choices and beliefs. Certainly it will still be here after everything else is gone, an enduring monument holding the 102-ton legacies of millions of Angelenos. Landfills, Big Mike likes to say, are forever.

For now, Puente Hills is a living, breathing landfill—with a deadly “breath” expelled in massive burps that must constantly be siphoned off or risk disaster, a reeking, highly explosive, climate-destroying exhalation capable of turning green grass brown in short order. This property of buried garbage proved a difficult lesson in the bad old days of trash disposal early in the twentieth century, when cities routinely used trash and ash to fill in swamps and mudflats. (Such areas were regarded as bothersome wastelands impeding progress back then; we call them irreplaceable, vital wetlands and endangered habitats now that we’ve destroyed most of them.) Housing projects, stadiums, parks and other developments that were planted atop early fills suffered from unexplained stenches, vermin infestations, swarms of roaches and, once decomposition had reached critical mass, methane fires and explosions. Long Island, San Francisco and a hundred other places in between all learned this the hard way: Trash can be deadly when you bury it. Puente Hills’s deep, aging refuse pile produces a constant flow of 31,000 cubic feet a minute of landfill gas (roughly half methane, half carbon dioxide, with traces of various pollutants mixed in). If allowed to bottle up within the landfill, it could turn Garbage Mountain into something resembling a fiery trash volcano. This is the flow that generates 50 megawatts of electricity around the clock and provides power for all landfill operations to boot. You’d have to cover 250 acres (or two and a half Disneylands) of sun-drenched Mojave Desert with parabolic mirrors to generate an equivalent output of solar power. At Puente Hills, the gas is expected to continue to flow for at least another twenty years

after

the landfill accepts its last piece of garbage.

Which is another way of saying that Puente Hills is big. Really big. It covers 1,365 acres, half of that space devoted to buffer zone and (oddly enough) wildlife preserve. The other half—a plot about the size of New York City’s Central Park—is devoted strictly to trash, which by 2011 had reached heights greater than five hundred feet above the original ground level. If the trash mounds of Puente Hills were a high-rise, they would be among the twenty tallest skyscrapers in Los Angeles, beating out the MGM Tower, Fox Plaza and Los Angeles City Hall. Puente Hills is big enough to have its own microclimate and wind patterns, which the crews are constantly battling with berms and deodorizers and giant fans, trying to keep noxious odors from wafting through the surrounding bedroom communities of Whittier and Hacienda Heights.

Landfills are usually thought of, when they are thought of at all, as out-of-the-way things. Nobody really wants to think about what they contain: Puente Hills harbors millions of tons of moldering old carpet, even more rotting food and a good 3 million tons of dirty disposable diapers—2.5 percent of the total landfill weight consists of soiled Pampers, Huggies and all the other sweet names for some very noxious refuse. The material that seeps out of it, a noxious brew called “leachate,” is so toxic that it has to be contained by multiple clay, plastic and concrete barriers, drainage systems and a network of testing wells just to keep it dammed and prevent it from poisoning groundwater supplies. The landfill workers didn’t start trying to restrain this toxic goop by putting down strata of waterproof plastic liners under incoming trash until 1988—almost no American landfill did. So there are millions of tons of garbage at the bottom, oozing downward, a closely monitored potential time bomb. Every landfill started before 1991, when tougher federal regulations finally kicked in to make liners a requirement, is the same.

Yet this Garbage Mountain is not set in the hinterlands, neither out of sight nor out of mind. It lies smack in the middle of the most populous urban sprawl in America, the Los Angeles Basin, rising up to dominate its low-slung skyline for miles, a misshapen mound planted with thirty different species of trees and shrubs in a bold and ultimately futile attempt to mask its true nature.

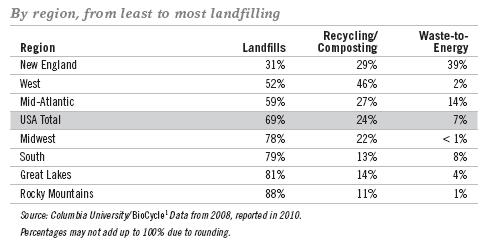

THE STATE OF GARBAGE IN AMERICA: WHERE DOES IT GO?

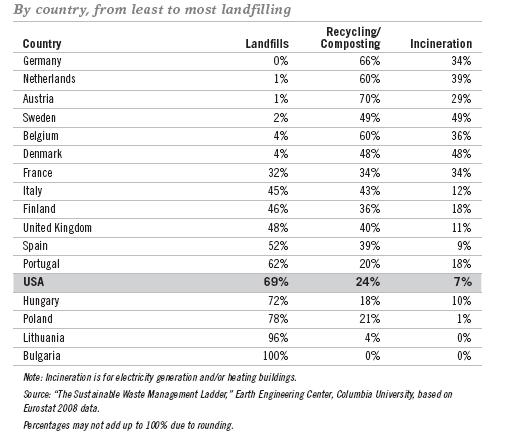

THE STATE OF GARBAGE IN THE WORLD: WHERE DOES IT GO?