Garbology: Our Dirty Love Affair With Trash (8 page)

Read Garbology: Our Dirty Love Affair With Trash Online

Authors: Edward Humes

Tags: #Travel, #General, #Technology & Engineering, #Environmental, #Waste Management, #Social Science, #Sociology

His life’s work, like that of the marketing and design industries he helped create and lead, was dedicated to preventing that from happening, to erase thrift as a quintessential American virtue, and replace it with conspicuous consumption powered by a kind of magical thinking, in which the well would never go dry, the bubble would never burst, oil and all forms of energy would grow cheaper and more plentiful with time, and the landfill would never fill up.

Lippincott is a fascinating historical figure, erudite, brilliant, seemingly easygoing. But there was nothing easygoing about his approach to reinventing the American consumer. With a team of 130 psychologists, sociologists, anthropologists and industrial designers backing him up, he mastered the art of making a product or a company or a concept appear to be something it was not. This was not the flimflam of the confidence man or the deceitful quackery of the snake oil salesman, but the art of the spinmeister—not hiding or breaking the truth so much as redefining it. He was helping to rewrite America’s mythology. Eastern Airlines’ noisy planes became “Whisperjets.” U.S. Rubber, whose tires sold poorly abroad because of anti-American sentiment, became “Uniroyal.” The gas station chain with an eye-glazing name and a reputation for poor service, Cities Service Oil Company, became the peppy “CitGo.” Lippincott was so successful at designing to redefine that he was hired by the U.S. Navy to reimagine the interior of the Nautilus nuclear submarine to make its cramped quarters appear spacious, and by the U.S. Treasury Department to make the Internal Revenue Service appear more user-friendly (his one great failure, it seems, as the IRS apparently declined to change its name to something kinder and gentler). The rebranding, design and corporate identity industry Lippincott helped create succeeded beyond his wildest expectations. He helped make short-lived, disposable products and rising amounts of consumer waste appear to be virtues. He didn’t hide the shortcomings previous generations would have identified in these products. He celebrated them.

It’s no coincidence that the notion of saving up to buy something (and earning interest in the process) started losing ground in his era, supplanted by the then-new phenomenon of credit cards and borrowing to buy (and

paying

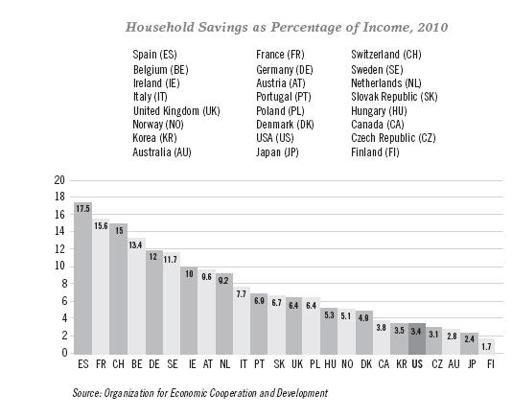

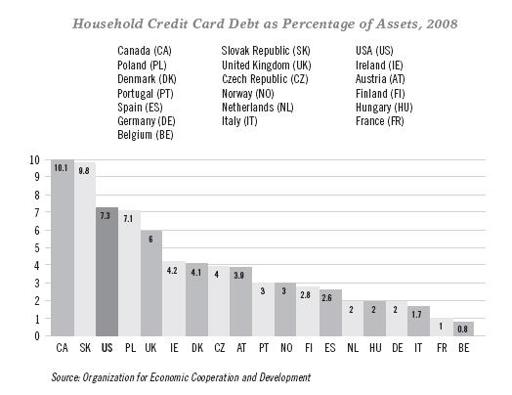

interest in the process). Political leaders who once fretted that Americans didn’t save enough compared to the citizens of other wealthy nations, a disparity that still holds true today, eventually stopped complaining as the credit industry became a major force in the rise and fall of the American economy (and a major source of political campaign donations as well, more than $32 million a year leading up to the current financial crisis). The normalization of what was once unthinkable, even shameful—large amounts of consumer debt—added decades of longevity to the Lippincott vision of throwing out and buying more at an ever-increasing rate in order to manufacture boom times. Average household credit card debt topped the landmark of $10,000 in 2006, a hundredfold increase over the average consumer debt in the 1960s. One consequence: Much of the material buried in landfills in recent years was bought with those same credit cards, leading to the quintessentially American practice of consumers continuing to pay, sometimes for years, for purchases after they become trash.

There were others at the time of this transformation who took an opposing view, who urged the country to reject “a society built on trash and waste,” as the journalist and best-selling author Vance Packard saw it. Packard, whose first book had created a sensation in 1958 by citing examples of subliminal advertising and other manipulative imagery he accused the Lippincotts of the world of employing, wrote a prophetic follow-up in 1960 called

The

Waste Makers

. In it, he accused his industry and marketing critics of sparking a crisis of excess and waste that would exhaust both nation and nature, until future Americans were forced by scarcity to “mine old forgotten garbage dumps” to recover squandered resources.

“Wastefulness has become a part of the American way of life,” Packard wrote. “Some marketing experts have been announcing that the average citizen will have to step up his buying by nearly 50 per cent in the next dozen years, or the economy will sicken. In a mere decade, advertising men assert, United States citizens will have to improve their level of consumption as much as their forebears had managed to do in the two hundred years from Colonial times to 1939 … The people of the United States are in a sense becoming a nation on a tiger. They must learn to consume more and more or, they are warned, their magnificent economic machine may turn and devour them. They must be induced to step up their individual consumption higher and higher, whether they have any pressing need for the goods or not. Their ever-expanding economy demands it.”

Packard couldn’t foresee the details of this buy-more future, just the general momentum of the times sweeping the country in that direction. His was one of the first voices to suggest that growth, Lippincott’s economy of abundance, had limits, and that resources would eventually be used up. A prudent country, he argued a half century ago, should start planning to shift its economy away from consumption and rapidly paced planned obsolescence, and base it more on conservation, durability and elimination of waste before it was too late.

This view was mockingly dismissed at the time as Luddite pessimism. But not even Packard imagined Americans would achieve a 102-ton waste legacy. In his world, a household had one telephone, one television, one car, and the least of them were expected to last ten years or more—and that was a

prosperous

household. The idea that all members of a typical family, even young children, would someday have their own phones, and that Americans could pay several hundred dollars a month for this “necessity”—for cell phones that would become high-tech trash in two years or less—would have seemed so absurdly wasteful to Packard that he would have dismissed the idea as too fanciful. Yet this is the sort of evolution he predicted would have to occur as marketers labored to transform yesterday’s waste and excess into today’s normal and necessary. He just never thought it would go that far.

Packard’s argument made sense and plenty of people bought his books. Not so many bought into his central premise, however, as Americans showed no inclination for embracing a retreat from consumerism. In 1960, his pessimistic, anti-materialistic views and prescriptions just could not compete with Lippincott’s vision of endless abundance. People didn’t want to see the waste—even Packard conceded as much. The overflowing trash cans were just more evidence of America’s productivity. Indeed, fifty-one years later, in 2011, America’s leaders were still looking at the world through Lippincott’s eyes, even as they proved Packard correct by publicly stating that the best hope for pulling the country out of recession and unemployment—that is, the best way to get the tiger to stop biting us—would be for American consumers to shop the country out of trouble. Fifty years after Eisenhower, the message remained the same: Buy anything. Then throw it away and buy some more.

T

HIS RISE

of consumerism and the new American Dream launched during television’s golden age was accompanied by another trash-boosting trend—the plasticization of America.

Municipal waste was only .4 percent plastic by weight in 1960. Our trash cans had almost no plastic inside them back then, but that began to change rapidly. By the end of the sixties, plastic trash had increased sevenfold. By the year 2000, American households were throwing away sixty-three times as much plastic as in 1960, and nearly 11 percent of the stuff in our bins each week was made of synthetic “miracle” polymers. Plastic had become the second weightiest component of garbage next to paper, which, as daily newspapers in America have declined, is a shrinking category of waste.

These figures, which come from the Environmental Protection Agency, actually underestimate the impact of plastic ubiquity, because plastics are the lightest trash we make. If the components of American trash were measured by volume or pieces rather than weight, plastic would rate as an even larger portion of what we throw away. Consider the plastic shopping bag, which didn’t exist in 1960. By the year 2000, Americans consumed 100 billion of them a year, at an estimated cost to retailers of $4 billion—costs passed on to consumers. Most of these bags land in landfills, though many go astray—plastic bag waste was the second most common item of trash found on beaches during 2009’s International Coastal Cleanup Day (with cigarette butts taking first-place honors). Their relatively small weight masks plastic bags’ enormous impact.

The new age of plastic went hand in hand with another trash-making trend of the era: the rising popularity of disposable products. These appeared on the scene in rapid succession: the invention of Styrofoam by Dow Chemical in 1944; the plastic-lined paper cup in 1950; the first TV dinner (turkey, mashed potatoes and peas on a one-serving, one-use plate and package) from Swanson Foods in 1953; the invention in 1957 of high-density polyethylene plastic, which would be used in the now-common gallon milk jugs that displaced reusable glass bottles; the 1958 introduction by Bic of the first disposable pen, followed by the 1960 marketing of the first disposable razors. There was a wave of such products, touching every part of the household and daily life, from plastic bread bags to non-refillable aerosol cans to the original paper Dixie cups. Dixies were initially despised for their wastefulness at the dawn of the twentieth century, but they were eventually accepted as tools for disease prevention in lieu of the traditional public glasses and ladles. (The product’s original name had been the “Health Kup.”) All of these new materials and products not only supplanted longer-lasting ones that could be reused many times and thereby remain outside of the waste stream, they also introduced a number of synthetic and potentially toxic waste materials into our refrigerators, medicine chests, cupboards, oceans, town dumps, natural habitats and our bodies.

One of the biggest shifts toward the modern throwaway economy came from the ultimate artificial necessity, a food product with no nutritional value and plenty of unhealthful effects, from obesity to dental decay: soda. In 1964, Coca-Cola decided it was finished with reusable glass soda bottles and introduced the “one-way” container, intended to be thrown out even though it was still glass and inherently reusable. Consumers embraced the convenience. The soda company was freed from the chains of local bottling plants (and local workforces) where bottle returns were cleaned and refilled. Three years later, the invention by DuPont scientist Nathaniel Wyeth of a plastic soda bottle that did not explode overnight in the refrigerator as its experimental predecessors had done—the polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastic container—led to the marketing of the now ubiquitous two-liter disposable soda bottle. It and its smaller relatives have dominated the soft-drink industry ever since, ending a half-century age of reusable glass containers. Decades of recycling efforts followed that have yet to equal 1960 levels of soda sustainability.

At the time of this switch to plastic, the soda manufacturers cited the convenience, simplicity, lower weight and lower cost (to the manufacturers, at least) that made disposable plastic bottles the preferred and sensible choice over glass. It was progress. The market had “spoken.” The notion that one-use containers made of fossil fuels—containers that never decompose—would inevitably impose a substantial cost on taxpayers, ratepayers, local sanitation departments and the environment was not considered in the industry’s cost-benefit analysis favoring the plastic soda bottle. The reason for that omission was simple: The beverage companies did not have to pay those costs; such costs were, to use the corporate term, “external,” which is a nice way of saying someone else has to foot the bill for a company’s business plan. The new consumer economy, in effect, encouraged and subsidized the creation of new and greater volumes of trash—which, in the case of the soda industry, amounts to just under 10 billion cases of soft drinks a year in the U.S. alone. How much trash is that? Soft drinks are America’s favorite beverage, quaffed daily by half the U.S. population over two years old (70 percent of males age two to nineteen drink sugary beverages daily, with the same age group of females right behind at 60 percent).

1

Annual consumption exceeded 50 gallons for every person in the nation beginning in 2002, more than twice the rate of soda drinking in 1960. (This is also twice the current per capita soda consumption in the number two soda-guzzling nation, Ireland; three times the soda drunk by Germans; five times the French; and ten times the Japanese.)