Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler (28 page)

Read Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler Online

Authors: Simon Dunstan,Gerrard Williams

Tags: #Europe, #World War II, #ebook, #General, #Germany, #Military, #Heads of State, #Biography, #History

THIS WAS THE QUESTION ASKED

by the first Soviet troops to enter the Führerbunker at 9:00 that morning. A few days earlier, on April 29, a special detachment of the SMERSH (NKVD counterespionage) element serving with the headquarters of the 3rd Shock Army had been created at Stalin’s insistence, specifically to discover the whereabouts of Adolf Hitler, dead or alive. The SMERSH team arrived at the Reich Chancellery moments after its capture by the Red Army. Despite intense pressure from Moscow, its searches proved fruitless. Although the charred bodies of Joseph and Magda Goebbels were quickly found in the shell-torn garden, no evidence for the deaths of Adolf Hitler or Eva Braun was found.

Close behind the assault troops and NKVD officers, a group of twelve women doctors and their assistants of the Red Army medical corps were the first to enter the bunker in the early afternoon of May 2. The leader of the group spoke fluent German and asked one of the four people then remaining in the bunker, the electrical machinist Johannes Hentschel,

“Wo bist Adolf Hitler? Wo sind die Klamotten?”

(“

Where is Adolf Hitler

? Where are the glad rags?”). She seemed more interested in Eva Braun’s clothes than in the fate of the Führer of the Third Reich. The failure to find

an identifiable corpse

would vex the Soviet authorities for many months, if not years. That day, the Soviet official newspaper

Pravda

declared, “The announcement of Hitler’s death was a

fascist trick

.”

This 1945 photograph shows the New Reich Chancellery devastated after years of bombing and the savagery of the Battle of Berlin. Constructed as the centerpiece of the Thousand-Year Reich, this grandiose building lasted less than a decade. This view shows the Courtyard of Honor with two armored cars parked on the left. These were always on hand in case Hitler needed to escape Berlin in an armored vehicle. In any event, they were not used.

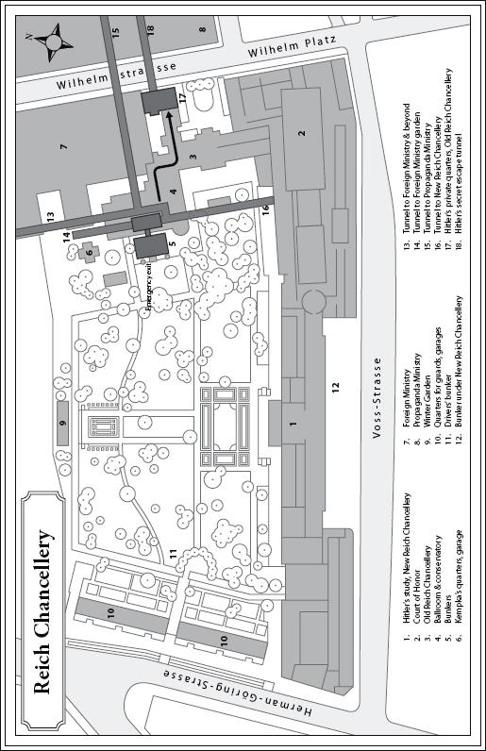

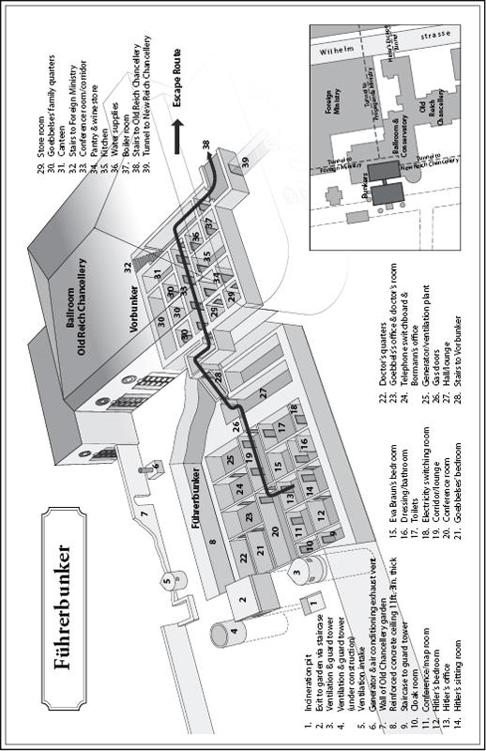

THE FÜHRERBUNKER, under the rear and the garden of the Old Reich Chancellery building on Wilhelmstrasse in the government quarter of Berlin, was built in two phases. The contractor was the Hochtief AG construction company, through its subsidiary the Führerbunkerfensterputzer GmbH—which also built the Berghof, Hitler’s Bavarian mountain retreat, as well as his Wolf’s Lair in Rastenburg. The initial Führerbunker structure, which later became known as the Vorbunker (ante-bunker), was intended purely as an air raid shelter for Hitler and his staff in the Reichskanzlei (Reich Chancellery). Construction began in 1936 and was usefully obscured by the work on a new reception hall then being built onto the western, rear face of the Old Chancellery. The construction of Albert Speer’s massive New Chancellery building, fronting onto the Voss-Strasse and adjoining the Old Chancellery in an L-shape to the south, was essentially complete by January 1939. This range of buildings, and the adjacent SS barrack blocks aligned north–south on Hermann-Göring-Strasse to the west, incorporated from the start two very large complexes of linked underground shelters, working quarters, garages, and tunnels.

On January 18, 1943, in response to the heavier bombs then being used by the Allied air forces, Hitler ordered Speer to extend the shelter under the Old Chancellery by constructing a deeper complex. Under the supervision of the architect Carl Piepenburg, an excavation for this Führerbunker or

Hauptbunker

(main bunker), code-named “B207,” was dug below and to the west of the Vorbunker. The major works were completed in 1943, at a cost of 1.35 million reichsmarks—five times the amount of the original shelter. However, it was not until October 23, 1944, that Dr. Hans Heinrich Lammers, the state secretary of the Reich Chancellery, was able to inform Hitler that the new facility was entirely ready for his use.

The new bunker lay twenty-six feet below the garden of the Old Chancellery and 131 yards north from the New Chancellery building. Two floors deeper than the Vorbunker, the Führerbunker adjoined its west side and was linked to it by a corridor, an airtight compartment, and a staircase down. The new complex had two main means of access: this route from the Vorbunker and another staircase from the far end leading up to the Chancellery garden. The ceiling of the Führerbunker was formed of reinforced concrete that was 11 feet, 3 inches thick; the external walls were up to 13 feet thick, and heavy steel doors closed off the various compartments and corridors. The bunker was built in Berlin’s sandy soil below the level of the water table, so pumps were continuously at work to keep the damp at bay. The complex incorporated its own independent water supply and air-filtration plant, and it was lit and heated with electricity generated by a diesel engine of the type used on U-boats.

The

general layout of the Führerbunker

was a series of rooms leading off each side of a central corridor, divided into outer and inner ranges. The outer range, nearest to the access from the Vorbunker, contained the practical amenities such as machine rooms, stores, showers, and toilets. The inner half of the corridor functioned as a reception and conference space, and leading off it were telephone and telegraph rooms; a first aid station; quarters for orderlies, valets, and medical personnel; and the Führer’s private quarters. Beyond a small refreshment room, these comprised a study, a living room, and Hitler’s bedroom and bathroom; from the bathroom a second door led to Eva Braun’s bedroom and dressing room. None of these rooms was larger than 140 square feet. Comfortably furnished with items brought down from the Chancellery and with paintings lining the walls, the bunker complex had a kitchen stockpiled with luxury foods and wines. It has been portrayed in movies as a drab, damp, concrete cellar, but while conditions certainly deteriorated in late April 1945, when leaking water and dust from the shelled streets above penetrated into the upper parts of the complex, some late visitors to the Führerbunker—such as the pilot Hanna Reitsch—described it as “luxurious.”

The bunker’s major weakness was that it had never been designed as a Führerhauptquartier, or command headquarters. After the intensity of Allied bombing forced Hitler and his staff to move underground permanently in mid-February 1945, the means of communication were woefully inadequate for keeping in touch with daily developments in the conduct of the war. The telephone exchange, more suited to the needs of a small hotel, was quite incapable of handling the necessary volume of traffic.

Apart from the Vorbunker’s above-ground access to the Old Chancellery building, three tunnels provided the upper Vorbunker with underground links. One led north, to the Foreign Office; one crossed the Wilhelmstrasse eastward, to the Propaganda Ministry; and one ran south, linking up with the labyrinth of shelters under the New Chancellery. However, the Old Chancellery—a confusing maze of passages and staircases, much altered over the years—also had an underground

emergency exit

to a third, deeper, secret shelter, known to only a select few. Hitler maintained his private quarters in the Old Chancellery throughout the war until forced underground in February 1945. To get to the secret shelter, Hitler did not have to leave his private study: as part of Hochtief’s extensive underground works, a tunnel had been built that connected Hitler’s quarters directly with the shelter. The tunnel was accessible via a doorway covered by a thin concrete sliding panel hidden beside a bookcase in the study. This tunnel, in turn, was connected to the Berlin underground railway system by a five-hundred-yard passageway. The third shelter had been provided with its own water supply, toilet facilities, and storage for food and weapons for up to twelve people for two weeks. Bormann had never really planned for it to be used; it was simply one of the range of options available to get Hitler out of Berlin. But by Friday, April 27, 1945, it was the obvious means of escape to take the Führer away from the devastating shells that were raining down on the government quarter of Berlin as Soviet troops fought their way in from three directions.

DESIGNED BY HITLER’S favorite architect, Albert Speer, the New Reich Chancellery was to have been the seat of power of the Thousand-Year Reich. During the war as the Allied bomber offensive intensified, the Führerbunker was built to protect Hitler from the increasingly devastating aerial bombs employed by the RAF and USAAF.

IN THE FINAL months of the war, Adolf Hitler retreated to the depths of the Führerbunker beneath the Old Reich Chancellery; Bormann had organized a secret tunnel that allowed the Führer and his select companions to escape via the Berlin subway system to an improvised airstrip and flee to Denmark and onward to Spain and Argentina.

ON THAT DAY, IN THE PRIVATE STUDY

in the bunker, Eva Braun was seated at the table, writing; Hitler was fidgeting on the sofa. An SS bodyguard stood to attention at the open doorway. Hitler walked over to him and asked about casualties outside; the dull thud of artillery shells could be heard and felt even this far underground and through the thick walls. The SS officer recalled that Hitler then appeared to make a decision.

Speaking as if

to an assembled audience, the leader of the collapsing Third Reich said that as long as he lived there could never be a hope of conflict between the Western Allies and Russia. But his was a difficult decision: alive, he would be able to lead the German people to final victory—but unless he died, the conditions for that victory could never be achieved. “Germany,” he said, “can hope for the future only if the whole world thinks I am dead. I must …”—his words tailed off.

The mesmerized SS man was brought sharply out of his riveted attention and saluted smartly as two of the half-dozen most

powerful and dangerous men

in the Nazi hierarchy entered the room: Reichsleiter Martin Bormann and SS and Police Gen. Heinrich “Gestapo” Müller, head of the Secret State Police. The guard was dismissed. Bormann and Müller brought news for Hitler alone, and it shook him to the core: Fegelein had divulged a thorough account of how Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler—the Führer’s “loyal Heinrich”—was negotiating with the Allies for the surrender of German forces in the West.