Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler (30 page)

Read Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler Online

Authors: Simon Dunstan,Gerrard Williams

Tags: #Europe, #World War II, #ebook, #General, #Germany, #Military, #Heads of State, #Biography, #History

GUSTAV WEBER HAD BEEN STANDING IN FOR HITLER

since July 20, 1944, when the Führer had been wounded in the bomb attempt on his life at his Wolf’s Lair field headquarters near Rastenburg in East Prussia. Hitler had suffered recurrent aftereffects from his injuries; he tired easily, and he was plagued by infected wounds from splinters of the oak table that had protected him from the full force of the blast. (His use of penicillin, taken from Allied troops captured or killed in the D-Day landings, had probably saved his life.)

Weber had impersonated Hitler on his last officially photographed appearance, when he handed out medals to members of the Hitler Youth in the Chancellery garden on March 20, 1945. Weber’s uncanny resemblance to Hitler

deceived even those quite close to him

, and on that occasion the Reichsjugendführer (Hitler Youth National Leader) Artur Axman was either taken in or warned to play along. The only thing liable to betray the imposture was that Weber’s left hand suffered from occasional bouts of uncontrollable trembling. Bormann had taken Hitler’s personal doctor into his confidence, and SS Lt. Col. Dr. Ludwig Stumpfegger had treated Weber with some success. Weber was often kept sedated, but his trembling became more noticeable when he was under extreme stress.

Eva Braun’s double was simply perfect. Her name is unknown, but she had been trawled from the “stable” of young actresses that Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, the self-appointed “patron of the German cinema,” maintained for his own pleasure. The physical similarity was amazing, and after film makeup and hairdressing experts had done their work it was very difficult to tell the two young women apart.

Eva paused in the chamber to dash off a note to tell her parents not to worry if they did not hear from her for a long time. She handed it to Bormann, who pocketed it without a word (its charred remains would

later be found on the floor

—it was too much of a security risk for Bormann to allow it to be delivered). Bormann then saluted the group, shook Hitler’s hand, and led the counterfeit Führer and his soon-to-be bogus bride back up the tunnel to the Führerbunker.

In the anteroom of the third-level chamber, the fugitives donned steel helmets and baggy SS camouflage smocks. Hitler carried slung from his shoulder a cylindrical metal gas mask case; this contained the painting of Frederick the Great that had hung above his desk. Like his dog, this portrait by Anton Graff went everywhere with Hitler, and his final act in the bunker had been to remove the 16 x 11-inch canvas from its oval frame, roll it widthwise, and slide it carefully into the long-model Wehrmacht gas mask canister. It

fitted perfectly

.

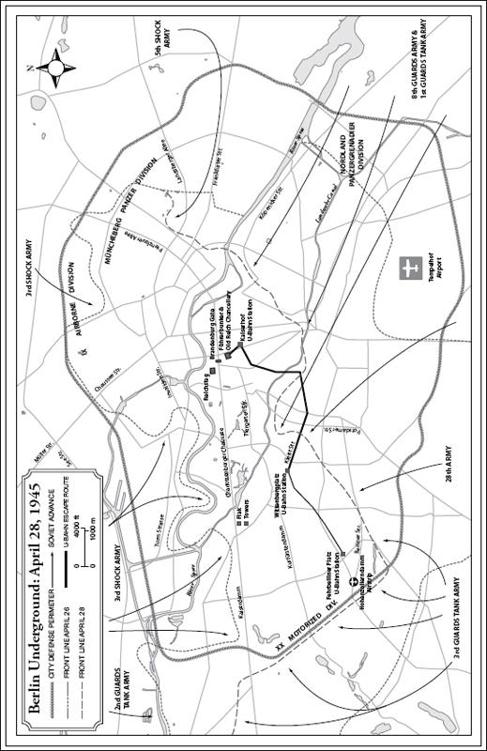

The party entered the U-bahn system near Kaiserhof (today, Mohrenstrasse) station. The walls were painted with a phosphor-based green luminous paint, so the flashlights hanging from the soldiers’ chests bathed the fugitives in an eerie glow. The tunnel was wet, and in places they had to slosh along ankle-deep in water as they made their way to the junction at Wittenbergplatz and on toward Fehrbelliner Platz. The stumbling four-mile journey took three hours, and they were goaded along not only by the sound of bursting shells overhead, but also by echoing small-arms fire in the distance—elsewhere in the system, Soviet and German soldiers were fighting in the railway tunnels.

As the group emerged onto the station concourse at Fehrbelliner Platz they were met by Eva’s other sister,

Ilse

, and by Fegelein’s close friend SS Gen.

Joachim Rumohr

and his wife.

In January 1945, Ilse had fled Breslau by train to Berlin to avoid the advancing Soviet forces. She had dined with Eva at the Hotel Adlon and—despite furious rows with her sister about the conduct of the war—had remained in the city until her brother-in-law Hermann Fegelein sent a detachment of “Leibstandarte” soldiers to fetch her. As for Joachim Rumohr, this was the second time in three months that he would escape from a ruined capital city just ahead of the Red Army. A former comrade of Fegelein’s, Rumohr had been wounded in February 1945 during the bloody fall of Budapest. Erroneously reported to have committed suicide on February 11 to avoid capture by the Russians, he had managed to reach the wooded hills northwest of Budapest and from there escaped to Vienna. Now his friendship with Fegelein guaranteed him the chance of another escape, this time with his wife.

When the fugitives reached the main entrance to the Fehrbelliner Platz station, they found three

Tiger II tanks

and two SdKfz 251 half-track armored personnel carriers waiting to take them on the half-mile drive to the makeshift airstrip on the Hohenzollerndamm.

THE ESCAPEES USED the Berlin U-Bahn system to reach a makeshift airstrip on Hohenzollerndamm where they boarded a Ju 52 piloted by SS Capt. Peter Baumgart.

RED SIGNAL LAMPS WERE PLACED along an eight-hundred-yard stretch of the wide boulevard, where troops had been set to clearing away debris and filling shell holes. At 3:00 a.m. on April 28, 1945, the lamps were lit, revealing a Junkers Ju 52/3m less than a hundred yards from the parked vehicles. The aircraft, assigned to the Luftwaffe wing

Kampfgeschwader 200

, had taken off in rainy conditions from Rechlin airfield, sixty-three miles from Berlin, just forty minutes earlier. Rechlin had long been the Luftwaffe’s main test airfield for new equipment designs, but in the closing weeks of the war it had reverted to more essential combat duties. It was one of several bases used by “Bomber Wing 200”—the deliberately deceptive title of a secret special-operations section of the air force commanded from November 15, 1944, by a highly decorated bomber pilot, Lt. Col.

Werner Baumbach

.

The Ju 52 that landed on the Hohenzollerndamm was flown by an experienced combat pilot and instructor named

Peter Erich Baumgart

, who now held the parallel SS rank of captain. More unusually, until 1935 Baumgart had been a South African, with British citizenship. In that year he had left his country, family, and friends and renounced his nationality to join the new Luftwaffe. In 1943 he had been transferred from conventional duties into a predecessor unit of KG 200; by April 1945 he was thoroughly accustomed to flying a variety of aircraft on clandestine missions, and his reliability had earned him the award of the Iron Cross 1st Class.

Baumgart prepared his aircraft for takeoff and his passengers boarded.

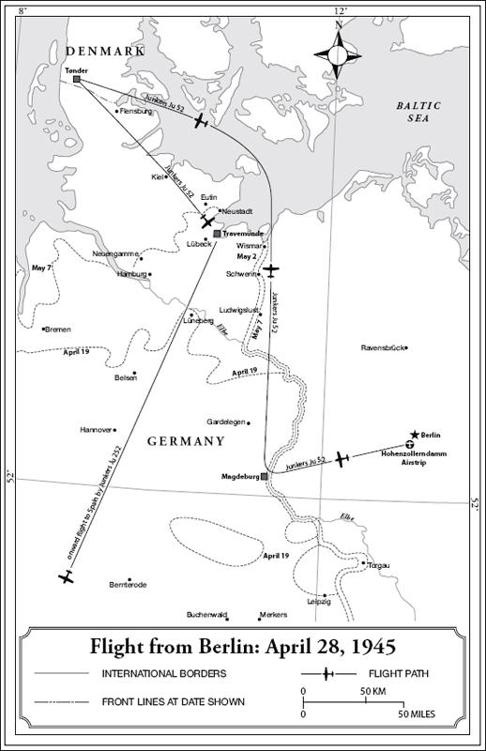

Baumgart’s orders were

to fly to an airfield at Tønder in Denmark, forty-four miles from the Eider River, which runs through northern Germany just below the Danish border. Thankfully, the rain in which he had taken off from Rechlin had now stopped, at least for the time being. Baumgart pushed the throttles forward, and the old “Tante Ju”—“Auntie Judy”—rattled and shook its way down the patched length of roadway until it lifted its nose into the air. It would take seventeen minutes to climb to 10,000 feet, where Baumgart could level and settle the Junkers at its cruising speed of 132 miles per hour. It was not until he was airborne and the escape party had removed their helmets that he realized who his main passengers were. Knowing that as soon as the daylight brightened he would be in grave danger from enemy aircraft, Baumgart motioned his copilot to keep a sharp lookout. It was essential to fly as far as possible in darkness at treetop level, given sufficient moonlight, to avoid marauding night fighters protecting the Allied heavy bombers flying between 15,000 and 20,000 feet. At Rechlin he had been promised an escort of at least seven Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighters, but there was no sign of them.

Baumgart would say later that he followed an indirect

flight plan

, landing for some time at Magdeburg to the west of Berlin to avoid Allied fighters and then flying northward through what the pilot said was an Allied artillery barrage to the Baltic coast. His luck held, and he encountered no further Allied aircraft before finally touching down on April 29 at Tønder, a former Imperial German zeppelin base. It was strewn with wrecked machines;

just four days earlier

, this field and that at Flensburg had been strafed by RAF Tempest fighters (of No. 486 “New Zealand” Squadron) that had destroyed twenty-two aircraft on the ground. As Baumgart closed down the engines and waited for the ground crew to approach, he caught sight of at least six Bf 109s dispersed around the field—the promised escort. Baumgart unbuckled himself and pulled the flying helmet from his head. In the rear he could hear his passengers getting ready to disembark; they had brought little luggage with them. He climbed out of his seat and walked back down the fuselage, coming to attention and saluting when he reached Hitler. The Führer took a step forward and shook his hand, and Baumgart was surprised to find that he was being slipped a piece of paper, which he put in his trouser pocket to look at later. He watched as the ground crew opened the door from the outside, and Hitler, Eva Braun, Ilse Braun, Hermann Fegelein, Joachim Rumohr, and Rumohr’s wife disembarked.

LEAVING FROM HOHENZOLLERNDAMM, the Ju 52 detoured to Magdeburg to avoid an Allied bomber group. Baumgart flew the Ju 52 on to the former German Imperial Zeppelin Base at Tønder in Denmark. The party transferred to another Ju 52 to reach the long-range Luftwaffe base at Travemünde, where they boarded a Ju 252 for their flight to Reus, near Barcelona, in Spain.

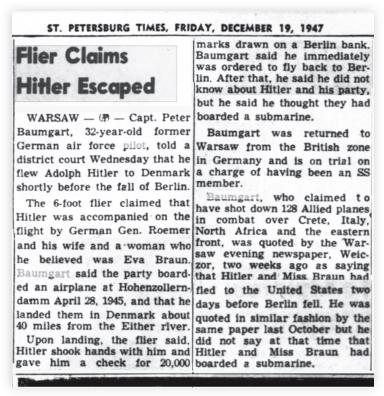

CAPT. BAUMGART HAD been sent for psychiatric tests when he first made these claims which the Associated Press and other news outlets reported in contemporary newspapers. Declared sane, he repeated his story in detail in court in Warsaw. Released in 1951, he was never heard of again.