Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler (31 page)

Read Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler Online

Authors: Simon Dunstan,Gerrard Williams

Tags: #Europe, #World War II, #ebook, #General, #Germany, #Military, #Heads of State, #Biography, #History

Friedrich von Angelotty-Mackensen

, a twenty-four-year-old SS lieutenant of the “

Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler

,” would claim to have seen Hitler on Tønder airfield. Wounded in the fighting around the government quarter on April 27, he and three comrades, including his superior, SS Lt. Julius Toussaint, had been lucky enough to be put aboard one of the last medical evacuation flights out of Berlin. Mackensen—running a fever and slipping in and out of delirium—was unable to remember the place from which he had left. He described lying on a stretcher in the dimly lit interior of the plane and asking for water. At Tønder, where he would have to wait for several days, he was carried out of the plane by his comrades and laid on the ground. At some point he heard somebody say, “The Führer wants to speak once more.” Mackensen was moved nearer and laid down again with a knapsack to pillow his head. Hitler spoke for about a quarter of an hour. He said that Adm. Karl Dönitz was now in supreme command of the German forces and would surrender unconditionally to the Western powers; he was not authorized to surrender to the Soviet Union. When Hitler finished speaking, the assembled crowd—estimated by Mackensen at about a hundred strong—saluted, and Hitler then moved among the wounded, shaking hands; he shook Mackensen’s, but no words were exchanged. Eva Braun was standing near an aircraft, which Hitler then boarded, and it took off.

For this next leg, on April 29, the Junkers was not flown by Capt. Baumgart, who was ordered to fly another aircraft back to Berlin for further evacuation flights. The piece of paper in his pocket turned out to be a personal check from Adolf Hitler for

20,000 reichsmarks

, drawn on a Berlin bank. The Führer’s aircraft returned to the field at Tønder, flying over it about an hour later, and a

message canister

was thrown down onto the airfield; it held a brief note to the effect that Hitler’s party had landed at the coast. Hitler’s flight from Tønder to Travemünde on the German coast northeast of Lübeck had taken the Ju 52 just forty-five minutes. Waiting there was Lt. Col. Werner Baumbach of the Luftwaffe, the commander of KG 200.

Baumbach had been assessing his diminishing options. At the start of that month, three huge six-engined

Blohm & Voss Bv 222

flying boats, with a range of at least 3,300 miles, had been made ready to take senior Nazis to safety. To provide another possibility, a four-engined

Junkers Ju 290

land aircraft with a similar range had also been ordered to Travemünde. Two of the flying boats were now at the bottom of the inlet, destroyed by Allied air attack. The Ju 290 had also been caught by strafing RAF pilots just as it landed on a specially lengthened concrete strip beside the shore; it was hit several times, forcing the pilot to overshoot, and had pitched over to one side, ripping off a wingtip. Baumbach had one Bv 222 flying boat left in the hangar, but he had never liked the type; its great size made it unwieldy, and although heavily armed it would be no match for an Allied fighter.

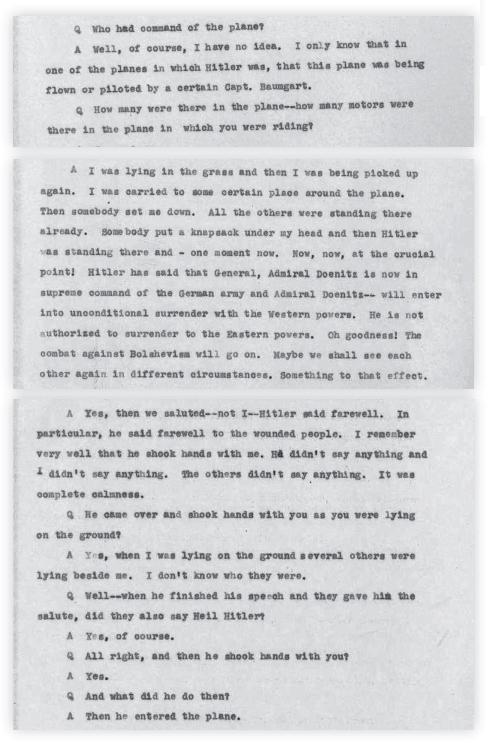

PART OF A lengthy March 15, 1948 U.S. interrogation of Friedrich von Argelotty-Mackensen, a wounded SS officer who had seen Hitler and Eva Braun at Tønder airfield after their flight from Berlin. He watched as they flew away to destinations unknown to him.

MARTIN BORMANN HAD FINALLY RECEIVED

confirmation from the Abwehr in Spain, through the modified T43 communications system, that an airfield had been made ready for the Führer’s arrival. Hitler would be flown to Reus in Catalonia, a region in which Generalissimo Franco’s fascists maintained an iron grip following their defeat of Catalan Republicans during the Spanish Civil War. Lt. Col. Baumbach personally drew up the flight plan. With the Ju 290 out of action, the mission would be entrusted to a trimotor Ju 252—a plane Baumbach knew well, having flown them during his time with KG 200’s 1st Group. While a descendant of the old “Tante Ju,” the Ju 252 was a vast improvement; its top speed was still only 272 miles per hour, but it had a range of just under 2,500 miles, a pressurized cabin, and a ceiling of 22,500 feet. It could reach the Spanish airfield at Reus, just over 1,370 miles away, with fuel to spare.

As the passengers disembarked from the Ju 52 at Travemünde after its short flight from Tønder, the Ju 252 was waiting on the tarmac with its engines already turning. Eva Braun now bade her sister Ilse a fond farewell—Ilse had decided to take her chances in Germany. Hermann Fegelein also embraced her. His own wife—Eva and Ilse’s sister Gretl—was heavily pregnant with their first child, and it had been considered too dangerous for her to flee with her husband. Bormann had assured his colleague that there would be plenty of time later to bring his wife and child to join him in exile. Joachim Rumohr and his wife had also decided to stay in Germany. Born in Hamburg, the cavalryman knew the countryside of Schleswig-Holstein well, and he felt sure he and his wife could find sanctuary there. (The overwhelming motive for Hitler’s hangers-on had been to escape the threat of Russian captivity; the Allied forces now advancing fast to the coasts north of Lübeck and Hamburg were from the British Second Army.)

The remaining members of the escape party then boarded the Ju 252,

and Baumbach saluted his Führer for the last time on German soil. As the aircraft rolled down the runway and took off, he felt great relief:

Thank God that’s over. I would rather leave some things unsaid, but it occurs to me that these diary notes may one day shed a little light on the strains, the desperate situation and maddening hurry of the last few days. At that time I had almost decided to make my own escape. The aircraft stood ready to take off. We were supplied with everything we needed for six months. And then I found I could not do it. Could I bolt at the last moment, deserting Germany and leaving in the lurch men who had always stood by me?

I must stay with my men

.

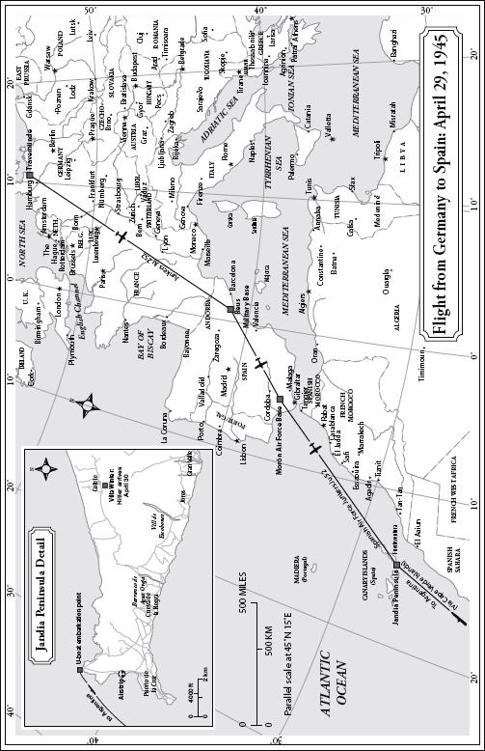

THE FINAL ESCAPE party—Hitler, Eva, Fegelein, and Blondi—flew to Reus in a long-range Ju 252 of KG 200. On arrival at Reus, a Spanish air force Ju 52 picked the party up for the flight to the Canary Islands. To eliminate evidence, the KG 200 aircraft was

dismantled

. Hitler and his party flew from Reus to Fuerteventura, stopping to refuel at the airbase at Morón, before arriving at the Nazi base at Villa Winter to rendezvous with the U-boats of Operation Seawolf.

THE SPANISH MILITARY AIRBASE

at Reus, eighty miles south of Barcelona, dated back to 1935. (During the Civil War there were three military airfields near Reus, the other two being at Maspujol and Salou.) After perhaps a six-hour flight from Travemünde, Hitler and his companions stepped down from the Ju 252. The crew lined up on the tarmac to salute; the Führer returned the compliment, and his party was taken away quickly in two staff cars to a low building on the edge of the airfield. The KG 200 pilot had been in radio contact with the military commander at Reus during his approach to the airfield, and that officer in turn had called the military governor of Barcelona. Fifteen minutes later a Spanish air force Ju 52 in national markings landed at the far edge of the field. The Ju 252 in which the party had arrived would be dismantled; there was to be no physical evidence that the flight had ever taken place, thus allowing Franco complete deniability.

The fugitives’ next stop would be the Spanish Canary Islands in the Atlantic, where Villa Winter, a top-secret facility, had been established on the island of Fuerteventura. From there they would embark on the next leg of their journey to a distant place of safety. For a number of other Nazis, however, Spain would be the final destination of choice.

On May 8, 1945—the day victory in Europe was celebrated—the wounded SS Lt. Friedrich von Angelotty-Mackensen was at last about to leave Tønder airfield in Denmark, destination Malaga. He would report that before his plane took off he saw another

recognizable figure

there: the Belgian SS Col. Leon Degrelle, the leader of the fascist Rexist Party and, as the highly decorated commander of the Belgian Waffen-SS contingent, a much-photographed personality. Degrelle had fled from Oslo that day in a Heinkel He 111H-23 bomber stripped out for passenger transport,

flown by Albert Duhinger

(who later lived in Argentina flying commercial aircraft). As a fighting soldier on the Eastern Front, Degrelle had earned Hitler’s respect; the Führer had once told him, “If I had a son, I would want him to be like you.” The Heinkel made it as far as Donostia-San Sebastián in northern Spain, right at the limit of its range, and Degrelle would survive the injuries he suffered when it

crash-landed

off a beach. On May 25, Degrelle was quoted as “expressing his belief that Adolf Hitler is alive and is in hiding.” A Spaniard who saw him in the hospital said

Degrelle had spoken

of visiting Hitler in Berlin the day before the Russians entered the city; the Führer had been preparing to escape and was in no mood for either suicide or a fight to the death.

Among other European collaborators to be offered a way out was Norway’s puppet leader,

Vidkun Quisling

. At his trial in Oslo in September 1945, he related how Josef Terboven, the Nazi Reichskommissar of Norway, had offered him passage in an aircraft or a U-boat to get to Spain or some other foreign country. Quisling said that as a “true patriot” he had refused the offer and stayed to face his countrymen; he would soon pay for this decision in front of a firing squad. At the beginning of May,

Pierre Laval

, the former Vichy French prime minister, was flown to Spain aboard a Ju 88. (Franco would expel him, and he too would be executed by his countrymen in autumn 1945.) It was reported that the Berlin ambassador of Italy’s rump Fascist republic,

Filippo Anfuso

, had also escaped late in April 1945, apparently aboard a “Croat plane.”

As early as April 26, 1945, Moscow Radio had charged that Spain was receiving Nazi refugees at an airfield on the Balearic island of Minorca. Quoting Swiss sources, the Soviets said, “To supervise the business,

Gen. José Moscardo

, an intimate of Franco … visited Minorca last month. Recent arrivals at the airdrome are the family of [Robert] Ley and several Gauleiters.”

Robert Ley

, the head of the German Labor Front since 1933, committed suicide while awaiting trial for war crimes at Nuremberg in October 1945. During his interrogation, however, Ley stated that when he last met Hitler in the bunker during April, the Führer had told him to “Go south, and he would follow.”

Albert Speer

, Hitler’s armaments minister, said much the same about a meeting in the bunker on Hitler’s birthday, April 20: “At that meeting, to the surprise of nearly everyone present, Hitler announced that he would stay in Berlin until the last minute, and then ‘fly south.’” SS Staff Sgt.

Rochus Misch

, the telephone operator in the Führerbunker, said, “There were two planes waiting to the north of Berlin. One of them was a Ju 390 [sic], and [the other] a Blohm & Voss that could fly the same distance. So Hitler could have escaped if he had wanted to.”

The feasibility of Hitler making a last-minute escape from Berlin was apparently accepted by the most senior Soviet officers. On June 10, 1945, the commander of the Soviet Zone in Germany, Marshal Georgi K.

Zhukov

, stated that Hitler “could have taken off at the very last moment, for there was an airfield at his disposal.” The Soviet commandant of Berlin, Col. Gen. Nikolai E.

Berzarin

, said, “My personal opinion is that he has disappeared somewhere into Europe—perhaps he is in Spain with Franco. He had the possibility of taking off and getting away.”