Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler (48 page)

Read Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler Online

Authors: Simon Dunstan,Gerrard Williams

Tags: #Europe, #World War II, #ebook, #General, #Germany, #Military, #Heads of State, #Biography, #History

CATALINA GOMERO WAS FIFTEEN YEARS OLD

when she went to live with the Eichhorns in 1945. She suffered from asthma and came from a poor family who believed she would have a better life at the Hotel Eden than they could offer her. Although a servant, Catalina was treated by the Eichhorns almost as a daughter. She said that Hitler arrived at their house in La Falda one night in 1949 and stayed for three days; she recognized him right away. “The driver must have brought him. He was put up on the third floor. We were told to take his breakfast upstairs and … knock at the door and leave the tray on the floor. He ate very well, the trays were always empty. Most of the meals were German.” He had shaved his moustache off. There were usually people in the house all day, but for those three days, the third floor was private. “Mrs. Ida told me, ‘Whatever you saw, pretend you didn’t.’ One of the drivers and I used to joke, ‘I saw nothing and you saw nothing.’ It was as if it had never happened. It was kept very, very secret.” Hitler left his clothes, including green canvas trousers and a black collared shirt, outside the room, and Catalina would clean and iron them. She took him three breakfasts, three lunches, and three complete teas. On the fourth day she was told he had left.

Eight days after the “important visitor” left La Falda, Mrs. Eichhorn told Catalina to pack a picnic lunch. With the chauffeur driving the Mercedes-Benz and Walter Eichhorn seated next to him, the four drove to the Eichhorns’ house on Pan de Azucar Mountain. This brick-and-timber construction had a large radio antenna and was part of the network of Nazi safe houses across the country. Hitler stayed for fifteen days at what the family called “El Castillo,” but after that Catalina never saw him again. However, she remembered taking telephone calls from him at the Eichhorn home through operators in La Rioja and Mendoza; she recognized his voice. The calls continued until 1962.

John Walsh

, an FBI agent stationed in Buenos Aires at this time, admitted the difficulties he and his operatives encountered in doing any undercover work in Argentina. Of the Hotel Eden and the Eichhorns, Walsh said, “We personally did not do surveillance work there. We would have sources that were outside the embassy that would do that. You just can’t walk in and say, you know, that you are looking for something.” Walsh said that he and his colleagues came under surveillance by the local police. A number of times when he was out with other agents they would see people who were obviously following and watching them.

DESPITE HIS DIRECT PROTECTION

by the “Organization” and the more indirect but essential collaboration of the Perón government, the fact that Hitler moved around during the late 1940s and early 1950s rather than remaining buried at the Center made sightings almost inevitable. In time, Catalina Gomero would not be the only person willing to tell stories of meeting the former Führer in Argentina after the war.

Jorge Batinic

, a bank manager from the city of Comodoro Rivadavia in the southern Patagonian province of Chubut, vividly remembered the story told to him by his Spanish-born mother, Mafalda Batinic. In summer 1940, she had been in France working for the International Red Cross, and on several occasions she had seen Hitler at close quarters when he was visiting wounded Wehrmacht soldiers. In later years she would often say, “Once seen, the face of Hitler was never forgotten.” After the war Mafalda moved to Argentina, and by the beginning of 1951 she was working as a nurse in the Arustiza y Varando private hospital.

One day, a German rancher was brought in for treatment for a gunshot wound, and a few days later three other Germans arrived to visit the patient. It was noticeable that two of them treated the third one as “the boss.” Mafalda had to choke back an involuntary cry of amazement when she recognized him as Hitler. He had no moustache and was somewhat graying, but she had no doubt that it was him. Shocked, Mrs. Batinic told the owners of the clinic, Drs. Arustiza and Varando; they watched him and were surprised, but did nothing. Apart from greeting the patient, Hitler hardly said a word. When the three Germans left, Mrs. Batinic asked the patient the identity of his important visitor. Realizing that she had already recognized the Führer, the injured rancher told his nurse, “Look, it’s Hitler, but don’t say anything. You know they’re looking for him, it’s better not to say anything.”

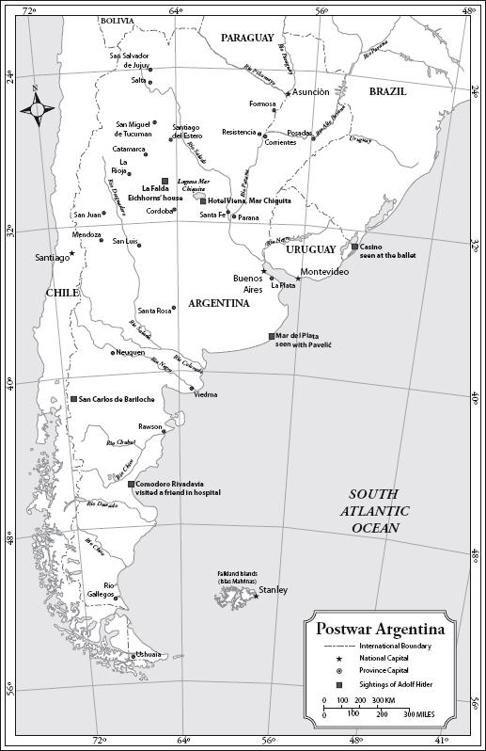

KEY SIGHTINGS OF Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun in Argentina post-World War II.

THE GERMAN NAZIS WERE NOT THE ONLY FASCISTS to escape to Argentina after the war. One of their most bloodthirsty allies had been

Ante Paveli , the leader of the Ustaše regime in the short-lived puppet state established by the Germans in Croatia. Styling himself the

, the leader of the Ustaše regime in the short-lived puppet state established by the Germans in Croatia. Styling himself the

Poglavnik

(equivalent to Führer), Paveli had been responsible for the murders of hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children of Serbian, Jewish, and other origins in the ethnic jigsaw puzzle of wartime Yugoslavia; even some members of the Gestapo had thought Ustaše methods “bestial.” Croatia was historically a Roman Catholic region, and contacts in the Vatican enabled Paveli

had been responsible for the murders of hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children of Serbian, Jewish, and other origins in the ethnic jigsaw puzzle of wartime Yugoslavia; even some members of the Gestapo had thought Ustaše methods “bestial.” Croatia was historically a Roman Catholic region, and contacts in the Vatican enabled Paveli and his whole cabinet, followed later by his wife, Mara, and their children, to travel along the ratlines to Argentina. The Perón government issued 34,000 visas to

and his whole cabinet, followed later by his wife, Mara, and their children, to travel along the ratlines to Argentina. The Perón government issued 34,000 visas to

Croats in the years after the war

. Indirectly, Paveli ’s escape from justice led to some of the clearest eyewitness testimony to Hitler’s presence in Argentina in 1953–54.

’s escape from justice led to some of the clearest eyewitness testimony to Hitler’s presence in Argentina in 1953–54.

A carpenter named Hernán Ancin met the Hitlers on several occasions in the 1950s, while he was working for Paveli as a carpenter in the Argentine coastal city of Mar del Plata. The Croatian former dictator had a property development business there. Paveli

as a carpenter in the Argentine coastal city of Mar del Plata. The Croatian former dictator had a property development business there. Paveli was known as “Don Lorenzo,” but one of his bodyguards said he had been president of Croatia. (Unsurprisingly, Hernán Ancin had never heard of him before—Paveli

was known as “Don Lorenzo,” but one of his bodyguards said he had been president of Croatia. (Unsurprisingly, Hernán Ancin had never heard of him before—Paveli was living under an assumed name and heavily protected, but he was not well known in Argentina for his crimes.) Ancin worked for Paveli

was living under an assumed name and heavily protected, but he was not well known in Argentina for his crimes.) Ancin worked for Paveli ’s company from the middle of 1953 to September or October 1954. In the southern summer of 1953, the Hitlers were regular visitors to the building site where Ancin was working. On the first occasion when the carpenter saw the two former dictators together, Hitler arrived with his wife and three bodyguards.

’s company from the middle of 1953 to September or October 1954. In the southern summer of 1953, the Hitlers were regular visitors to the building site where Ancin was working. On the first occasion when the carpenter saw the two former dictators together, Hitler arrived with his wife and three bodyguards.