Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler (50 page)

Read Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler Online

Authors: Simon Dunstan,Gerrard Williams

Tags: #Europe, #World War II, #ebook, #General, #Germany, #Military, #Heads of State, #Biography, #History

MARTIN BORMANN STAYED OUT OF POLITICS.

His interest now lay purely in protecting and multiplying the Organization’s funds. His trips to the valley became less and less frequent, as he distanced himself and his network from the ailing Hitler. He spent much of his time in Buenos Aires; his front was a company that manufactured refrigerators, behind which he extended his

financial dealings

across the world

. His regular meetings with President Perón were detailed by Jorge Silvio Adeodato Colotto, the head of Perón’s personal police bodyguard from 1951 until the coup against him in September 1955. Now eighty-seven, well over six feet tall, dressed smartly, and carrying a pocket Derringer pistol, Colotto remains an impressive figure, lucid and happy to talk to us about his time as the head of the former Argentine president’s personal security detail.

Colotto explained that while he was with Peron he wrote down every interesting episode about the president, including many one-liners, on small pieces of paper—and he had stored them all in a can! From this unusual archive of 6,200 papers, which Colotto had itemized and translated into an as-yet unpublished English-language book, came his recollection of a key encounter.

Colotto was present on one occasion in the spring of 1953 at Perón’s house on Teodoro Garcia Street in Belgrano, an exclusive suburb of Buenos Aires. This was the house that the Nazi “ambassador” Ludwig Freude had given to Evita as a wedding present in 1945. The twice-widowed president, who now used it for private meetings and romantic liaisons, would arrive wearing a hat and glasses as a disguise. (Another frequent visitor was the shipping magnate Alberto Dodero. He had fallen out with Perón in 1949 when the president nationalized his shipping interests at a fraction of their true value, but the rift did not last long.)

On this occasion, Colotto was on duty at the house when Perón told him, “Bormann is coming at 8:00 p.m. Be careful—he is German, not Argentine, and they are punctual.” At 8:00 sharp, Colotto was waiting at the door when Bormann arrived in a taxi. They shook hands, and the bodyguard showed him through to the president’s living room. Colotto remembers the Reichsleiter as “all German.” Bormann had grown a moustache and was wearing a jacket and tie. He spoke very little Spanish, but could make himself understood. Perón was in his office, and the bodyguard went to tell him his guest had arrived. When they met in the living room they greeted each other with a tight hug, like old friends; then they went to the office, where they stayed until 10:00 p.m. As the house was used mainly for clandestine meetings, Colotto said security was minimal. “There were two agents outside during the day when Perón was not there. But when Perón was there, the agents were dismissed. I was the only guard in the house when Perón was there.” Perón’s butler Romano and cook Fransisca were also in the house; the president was going to invite Bormann to stay for dinner, but the visitor said he had other commitments. When the two of them came out of the office,

Perón told Colotto to “walk with Mr. Bormann

” to Cabildo, an avenue three hundreds yards from the house, to get him a taxi. When Colotto returned, President Perón said, “Bormann gave me an undeserved present.” He did not say what it was, but Colotto guessed that it could have only been something small and valuable.

Colotto saw Bormann at the house on a second occasion during the weeks that followed, and the German’s presence in the capital became part of his working life. Bormann kept a suite at the

luxurious Plaza Hotel

, facing the Plaza San Martin at the end of Calle Florida, the world-famous shopping avenue in Buenos Aires. Colotto would go to the Plaza Hotel every month to pay Bormann’s expenses and accommodation with money that Perón gave him in a brown envelope. Bormann’s mistress, a German-Brazilian named Alicia Magnus, stayed there with him. Located across the plaza from the hotel are the impressive buildings of the

Círculo Mílitar

(a military club founded in 1881) and the Argentine Foreign Ministry, in an area that is also close to the banking district. Colotto thought Bormann held regular business meetings at the Círculo Militar.

ANOTHER WOMAN IN BUENOS AIRES

who was convinced she knew Martin Bormann well was Araceli Méndez, who had arrived in Argentina from Spain in 1947 when she was twenty-four. She met him in 1952 at a café in Buenos Aires; when he needed someone to write letters and documents in good Spanish, she introduced him to her brother. Araceli said that the relationship deepened; they became good friends, and she went to work for him. He told her that he was a senior Nazi and that the Curia (the Vatican papal court) had helped him to reach Argentina—he had been very specific about this phrasing. He also said that he had been in the hospital and had work done to alter his hairline.

Bormann apparently had

four or five different passports

; Araceli knew him as Ricardo Bauer, but he would also use the name Daniel Teófilo Guillermo Deprez, from Belgium. Under that name he was the owner of a factory that produced “Apis” refrigerators, on Ministro Brin Street in Lanús, Buenos Aires. Araceli Méndez ended up doing bookkeeping work for him in an office at Pasaje Barolo, and she claimed that he then began to woo her (his greed for sex seems to have been as great as his personal financial avarice). She witnessed many of his financial dealings; he once received a bank transfer for US $400,000 from Europe. He told her that he had shares in a factory in Belgium and another in Holland and that this transfer and many others were part of his profits. Bormann had also brought many precious stones from Europe, including one diamond that he sold in Buenos Aires for US $120,000.

THE RELEASED FBI FILES

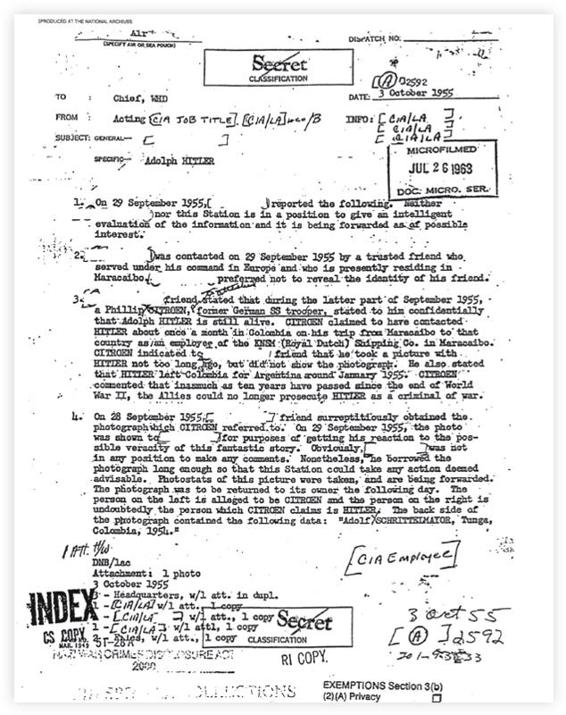

on sightings of Hitler in South America, sparse as they are, are relatively extensive when compared to the mere dribble of information that has come out of the Central Intelligence Agency, but one report from the agency’s Los Angeles office does stand out. This allegedly

placed the Führer in Colombia

in January 1955. While ultimately unconvincing, it is unusual in that it contains a very poor quality photostat of a photograph, alleged by the CIA informant’s contact (a former SS man named as Phillip Citroen) to show Hitler, using the identity of one Adolf Schüttelmayer (on the written report, shown on page 282, it is spelled “Schrittelmayor”). In the photo “Hitler”—who at this date would have been sixty-five—still has dark hair and the classic moustache, and it is thus at odds with other, apparently better-founded testimonies. The picture is marked “Colombia, Tunga, America del Sur, 1954.” There is a town of Tunja in central Colombia, but it has no known Nazi affiliations; indeed, after World War II it became home to many Jewish refugees from Europe.

The “secret” CIA report bears a disclaimer that neither the unnamed informant nor the Los Angeles station is “in a position to give an intelligent evaluation of the information and it is being forwarded as of possible interest.” Even so, the fact that the CIA’s Los Angeles office thought it worthwhile to do so is significant. Neither the FBI nor the CIA seems to have been convinced by the declaration, made with absolute confidence nearly ten years earlier by the British historian and former intelligence officer Hugh Trevor-Roper, that Hitler had died in the bunker—an assertion made despite a complete lack of forensic evidence.

A CIA DOCUMENT from 1955, detailing a report that Hitler was in Colombia.

UNDER THE PROTECTION OF PRESIDENT PERÓN

, Argentina had become a haven for German, French, Belgian, and Croatian fascists. They would meet Perón in his official residence, the Casa Rosada, facing the square at the eastern end of the Plaza de Mayo.

Rodolfo Freude

, son of Ludwig and friend of Evita’s brother Juan Duarté, managed the secret network of former Nazis’ contacts with the regime. He had risen to become Perón’s chief of presidential intelligence and had an office in the Casa Rosada.

Juan Perón was reelected president in June 1952 by a margin of over 30 percent (this was the first time that Argentine women had been able to vote). A month later, on July 26, 1952, his charismatic wife

Evita died of cancer

at the young age of thirty-three. By the time of her death she had spent much of the stolen money that she, in her turn, had stolen from Bormann, mostly to finance philanthropic work for the Argentine poor—her

descamisados

(literally, “shirtless”). The country went into mourning. Crowds kept vigil throughout the night in front of the presidential palace and later in front of the Ministry of Labor, where she was taken to lie in state. Carrying candles, people knelt in prayer in the wet streets, and women cried openly. On July 27, the whole country came to a standstill.

“Little Eva” had been Juan Perón’s lucky charm and his main hold on public affection. By 1955, much of the money the couple had taken had run out, and without her by his side his luck ran out with it. His economic reforms had divided the country, and a number of terrorist attacks and consequent reprisals were moving Argentine politics rapidly in the direction of yet another revolution. Ironically, the last straw was not some new oppressive measure, but Perón’s liberalizing plan to legalize divorce and prostitution. The leaders of the Roman Catholic Church, whose support for the president had been dwindling, now began to call him “

The Tyrant

.”

A serious blow to Perón’s popularity with those who worshipped the memory of Evita was a scandal, aired in the gossip pages of the press, concerning the fifty-nine-year-old president’s relationship with a thirteen-year-old girl named Nelly Rivas. He misjudged the public mood when he replied to reporters’ questioning about his girlfriend’s age, “So what?

I’m not superstitious

.” But his sense of humor soon failed him, and in response to what he perceived as the church’s support for the opposition he expelled two Catholic priests from the country. Pope Pius XII retaliated by excommunicating Juan Perón on June 15, 1955.

The following day, navy jet fighters flown by rebel officers bombed a pro-Perón rally in the Plaza de Mayo opposite the Casa Rosada, reportedly killing no fewer than 364 people. Maddened Perónist crowds went on a rampage, burning the Metropolitan Cathedral and ten other churches in Buenos Aires. Exactly three months later, on September 16, 1955, a Catholic group from the army and navy led by Generals Eduardo Lonardi and Pedro Aramburu, and Adm. Isaac Rojas, launched a coup from Argentina’s second city of Córdoba. It took them only three days to seize power.

Perón—who had himself come to power through the military coup of 1943—had never been blind to the danger of revolution. On Martin Bormann’s advice he had built his very own “Führerbunker.” On the ground floor of the Alas building at Avenida Leandro N. Alem in San Nicolas, Buenos Aires, a secret passage led to an underground vault lined with rosewood. A bedroom there had silk pajamas, an emergency supply of oxygen, and a walk-in wall safe. At the back of the safe was a plaster wall, concealing a long underground passage leading to a secret exit in the docks of Puerto Madero. It is not known if Perón used the bunker to escape through the cordon of troops closing in on him. It is known that he made it to Puerto Madero. Waiting there for Perón was a gunboat sent by Paraguayan dictator Alfredo Stroessner. Without bothering to collect his teenage lover, the once-and-future

president fled the country

.

THE “REVOLUCIÓN LIBERTADORA”

sent shockwaves through the Nazi community in Argentina. Bormann issued instructions to close the operations in the Estancia Inalco valley and arranged for Hitler to

move to a smaller house

where he could live in complete obscurity. Now accompanied only by his two closest aides—his personal physician, Dr. Otto Lehmann, and the former

Admiral Graf Spee

petty officer Heinrich Bethe—Hitler moved to a property called La Clara, even deeper within the Patagonian countryside. Bormann was the only one within the Organization who knew its location, and he told everyone else that this was necessary for the Führer’s security. Once again, he completely controlled access to Hitler. The frail, rapidly aging Hitler was now nothing more than a distracting problem for the international businessman Martin Bormann—a problem that time would solve, as the Führer faded away into an exile within an exile.