History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (38 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

Far from the amiable golf addict he was often depicted to be, Eisenhower was a proactive campaigner against any traces of leftist thought. In 1954, he allowed the CIA to stage a coup in Guatemala, ousting progressive Jacobo Arbenz on the grounds that the land reformer was a communist (Arbenz was not a communist, and only four of the fifty-one members of his coalition government were). In 1955, the United States endorsed Ngo Dinh Diem to be the first president of South Vietnam. Diem was autocratic, repressive, and Catholic in a predominantly Buddhist country, but he won American support because he was a fervent anticommunist.

Back in the United States, Ike perpetually spoke of reducing the deficit and directing more money to civilian rather than military projects, but in 1956 nearly 60 percent of the federal budget was going to defense (compared with 45 percent during the Vietnam War and less than 25 percent during the Reagan administration).

10

By 1957, Eisenhower widened his sights to the Middle East, where he requested two hundred million dollars from Congress to be spent as he saw fit to bolster anticommunist governments. He also insisted on immediate approval of any future deployment of troops to the region. Congress said yes to the money but no to what Senator Hubert Humphrey called “a predated declaration of war.”

11

The U.S. Sixth Fleet eventually did go to the Gulf region, landing fifteen thousand soldiers and marines to establish order in Lebanon. Ike also sent money and arms to Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Libya, and Saudi Arabia in an effort to isolate Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nassar, whom Eisenhower considered to be a communist. Unfortunately, Eisenhower did not count on internal rivalries destroying what little unity he was able to provide temporarily in the region. By 1959, his doctrine was largely abandoned, but it did establish a strong precedent for U.S. military involvement in the Middle East.

In July 1958, the ruling monarchy of Iraq was overthrown by the Iraqi army. Eisenhower believed the coup was directed by Gamal Nassar and carried out by communists, despite the fact that U.S. intelligence could find no proof that it was.

6

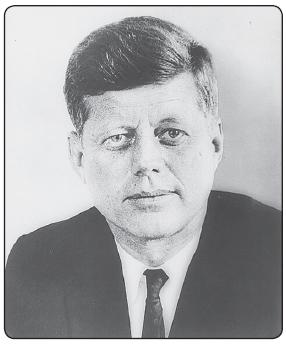

. KENNEDY DOCTRINE (1961)

“Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, in order to assure the survival and the success of liberty.” No doctrine had ever been so ambitious. In his inaugural address, John F. Kennedy used the words

globe

and

world

no fewer than twelve times. Paradoxically, Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev delivered an exceptionally similar speech that very same month, promising support for any nation seeking independence.

Kennedy’s violent death three years later forever changed the course of American history. It also blurred American memory. He had been elected in 1960 in part because he had presented the Eisenhower administration, and its vice president, as being soft on communism. Often viewed as a compassionate idealist, Kennedy was a hawk of the highest order, a case he made patently obvious at his inauguration, and he maintained a federal budget where 50 percent went straight to the Pentagon. When the Democratic Party honored their fallen leader at the 1964 National Convention, their platform publicly declared some of the great achievements that JFK had made possible over the preceding three years, including a 44 percent increase in tactical fighter squadrons, 45 percent increase in combat-ready army divisions, 150 percent increase in thermonuclear warheads and 200 percent increase in overall megatonnage, and an 800 percent increase in special forces.

12

Kennedy’s dual doctrine of massive nuclear deterrence and multiple ground operations was a natural outgrowth of the preceding administrations, only stated in a brazen display of one-upmanship. His focus on Cuba, resting only ninety miles from the Florida coast, had a historic and geographic legitimacy by way of the M

ONROE

D

OCTRINE

. Less defensible was Kennedy’s steady escalation in Southeast Asia. The country of most concern was, of course, Laos.

Before Dwight Eisenhower left office, he was entertaining the possibility of invading Laos and reinstating a right-wing government. The nation, according to Ike, could “develop into another Korea,” and the surrounding area would then succumb to the domino theory. Notably, in Ike’s security briefing to the young president-elect in January 1961, South Vietnam never entered the conversation.

13

He ran for office as an ardent anticommunist, and his inaugural address affirmed his oath to fight Marxism anytime, anywhere. After the fiasco of the Bay of Pigs, however, Kennedy learned to temper his aggression, relying instead on modest troop buildups and huge nuclear stockpiles to demonstrate American might.

But after the failed Bay of Pigs, Kennedy began to look toward Saigon, and its aggressively anticommunist government, as the best possible opportunity to score a low-cost victory against Moscow and erase the embarrassment of Cuba. A show of force was needed somewhere to prove he had the military chutzpa to back up his doctrine, a pledge he made on his first day on the job.

Proof that Americans are unpredictable when it comes to foreign policy, Jack Kennedy’s public approval rating hit a peak of 83 percent immediately after the failed Bay of Pigs invasion.

7

. NIXON DOCTRINE (1969)

Richard Nixon campaigned in 1968 on the premise he could bring “peace with honor” to the Vietnam conflict. He failed to do either. But he did implement a new method of battling communism that would become the U.S. modus operandi for the remainder of the Cold War.

July 25, 1969—Nixon was in Guam after meeting the returning crew of

Apollo XI

. In a small press conference, he mentioned a change in the way the United States would help friendly nations face external threats. Instead of sending troops, the United States would just send money, ordnance, and equipment. It was up to the nations themselves, he said, to supply the manpower. The idea was not unlike FDR’s L

END

-L

EASE

program at the start of the Second World War. “I made only one exception,” Nixon stated in his memoirs, “in case a major nuclear power engaged in aggression against one of our allies or friends, I said that we would respond with nuclear weapons.”

14

Many citizens, including Senate majority leader Mike Mansfield, interpreted this to be the Vietnam exit strategy promised by the president. Nixon abruptly corrected them. The doctrine “was not a formula for getting America

out

of Asia,” Nixon later wrote, “but one that provided the only sound basis for America’s staying

in

and continuing to play a responsible role.” He emphasized that point in a nationwide televised address on November 3, 1969, in what became known as his “Great Silent Majority” speech. The public reaction was overwhelming. Never before had the White House mailroom received so many letters and telegrams—eighty thousand in the course of a few days. Nearly all supported Nixon in full. An ensuing Gallup Poll registered a 77 percent approval rating for the president.

15

Another four years would pass before troops were withdrawn from Southeast Asia. In the interim, the United States funneled an increasing amount of money and material into Saigon. By 1973, most of the weapons, aircraft, and ships in the South Vietnam armed forces were American-made. But all that firepower could not save a government that was, at best, dysfunctional.

Sound policy or not, Nixon applied his doctrine in other areas of the world, especially the Middle East. After the departure of British troops from the region in 1971, the State and Defense departments provided funds and weapons to the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Also receiving assistance was Mohammed Pahlavi, the shah of Iran, a man whom Nixon had known since 1953. Though possessing a questionable human-rights record, the shah was viewed as a stabilizing force in the region, and he was allowed to purchase the most sophisticated conventional weapons available in the American arsenal.

It was through the Nixon Doctrine that Israel became a close ally to the United States, starting with the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Committing no troops, Nixon instead lobbied Congress to resupply Israel with billions of dollars’ worth of tanks, artillery, combat aircraft, and ammunition. Capitol Hill acquiesced, and Israel won the war, turning a relatively distant relationship between Washington and Jerusalem into one of the most diehard alliances on the planet.

16

At one point during the mid-1970s, half of all U.S. arms sales were to the shah of Iran. By the late 1970s, Israel received the majority of exported American arms.

8

. CARTER DOCTRINE (1980)

In 1903, Lord Lansdowne declared to Parliament, “We should regard the establishment of a naval base or a fortified port in the Persian Gulf by any other Power as a very grave menace to British interests, and we should certainly resist it by all the means at our disposal.” In 1980, Jimmy Carter announced in his State of the Union address, “An attempt by any outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf region will be regarded as an assault on the vital interests of the United States of America, and such an assault will be repelled by any means necessary, including military force.”

History does not repeat itself, but human behavior does. President Carter echoed Lord Lansdowne because the United States and the Soviet Union were beginning to assume the role long held by Great Britain and France in the Middle East. For more than a century, the rival Western European superpowers hovered over the precious linchpin to their Asian colonies. For the Eagle and the Bear, the goal was the Middle East itself and its vast reserves of oil.

17

Only nine months before his forceful doctrine statement (crafted in part by hawkish N

ATIONAL

S

ECURITY

A

DVISER

Zbigniew Brzezinski), Jimmy Carter had played the peacemaker in the C

AMP

D

AVID

A

CCORDS

. His aggressive change of mind came by way of several unsettling events. In late 1979, Islamic fundamentalists staged terrorist attacks in Saudi Arabia, Ethiopia and Somalia fought a border war, and radical students captured the U.S. Embassy in Tehran. Soon thereafter, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, an act that Carter embellished as “the most serious strategic challenge since the Cold War began.”

18

Strangely, the United States and the USSR failed where Britain and France at least endured. Indicative of the poor logic of the Carter Doctrine, the president found himself struggling against Muslim extremists in Iran and supporting them in the Afghan War, achieving little progress in either pursuit. The Soviets fared worse, losing fifteen thousand soldiers in ten years of miserable occupation of Afghanistan, unable to adapt to the harsh terrain and guerrilla warfare.

In protest of the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan, Jimmy Carter mandated that the United States boycott the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow, and sixty-four other nations joined the protest. Eighty-one nations still participated, including Afghanistan.

9

. REAGAN DOCTRINE (1985)

The aged Republican closely mimicked the policy of a youthful Democrat. Though less eloquent, Ronald Reagan’s anticommunism was just as intense as Jack Kennedy’s. Both claimed, incorrectly, that the Soviet Union held a superior edge in nuclear weapons technology. Both increased defense spending by large margins (11 percent for Jack and 44 percent for Ron in his first three years). They even had their own famous Berlin sound bite—“Ich bin ein Berliner” (1963) and “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall” (1987).

Not well versed in German, Kennedy basically said he was a jelly-roll. Rather dim on history, Reagan was unaware that the Berlin Wall was conceived and constructed by the German Democratic Republic, not the Soviet Union.

What they lacked in accuracy, they made up in conviction, and both men were committed to roll back the “red tide” rather than simply contain it. To accomplish this, both looked to weapons of mass destruction to secure the territorial United States, and both relied on small conventional actions to win the fight in the developing world.

19

The main difference between the two was how they viewed the Central Intelligence Agency. Kennedy lost faith after the CIA’s poor performance in the 1961 Bay of Pigs operation. Reagan, in contrast, believed the CIA to be the very best tool to combat communism on the ground, and he ushered in what is known as the “golden age” of covert operations. In June 1980, he indicated—if elected—exactly where he would fight the Cold War. In very simple terms, he explained the cause of instability in the world, especially in Central America and Africa. Ignoring the roles of poverty, disease, dictatorships, corruption, and ethnic hatred in the regions, Reagan declared, “Let’s not delude ourselves; the Soviet Union underlies all the unrest that is going on.” In his 1985 State of the Union address, he emphasized how he would fight: “We must not break faith with those who are risking their lives on every continent from Afghanistan to Nicaragua to defy Soviet-supported aggression and secure rights which have been ours from birth…Support for freedom fighters is self-defense.”

20