History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (60 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

It was all too much for Floride Calhoun, wife of Vice President John C. Calhoun. Obliged to socialize with the Eatons, the second lady initially demonstrated a cold civility and then avoided them altogether. Soon every cabinet member’s wife refused to be seen with the new Mrs. Eaton, a snub that grossly offended Jackson, whose own wife was the target of heartless ridicule (see E

LECTION OF

1828). Within a year, nearly all of “polite society” had ostracized Margaret, including Jackson’s niece Emily Donelson, the acting first lady. Jackson responded to the insult by banishing his niece from the White House.

95

Steadily, the intrigue and alienation of half of Washington took a toll on the president. His hair turned from gray to white, his eyes sank and turned permanently bloodshot. He cried easily. He lost weight. By 1830, he was losing patience, threatening to fire his entire cabinet and banning congressmen from the White House. He even threatened to dismiss ambassadors who did not openly accept the war secretary and his wife. When warned of the possible international ramifications of such an act, the president angrily responded, “I will show the world that Jackson is still the head of the government.”

96

The only person to show any sincere kindness toward Margaret was Secretary of State Martin Van Buren. A widower like Jackson, Van Buren was positive and friendly by nature, a cherry tree compared to Old Hickory. Already fond of the little New Yorker, Jackson began to view him as the next best hope for the presidency.

The deadlock finally broke in 1831 when department heads started to resign one by one. Triumphant, the president readily accepted. To save face, both Eaton and Van Buren also took their leave, much to Jackson’s disappointment. With the exception of his postmaster general, his entire cabinet had been cleaned out.

Remarkably, nothing illegal took place, and yet the event forced more high-level retirements than any scandal except for W

ATERGATE

. The shakeup, involving nothing more than social posturing and gossip, also changed the course of presidential history. Rejuvenated by his victory over the social elite, Jackson ran for reelection in 1832 and won. For his vice president and successor, he chose Martin Van Buren, the one man who stood by him and Margaret O’Neale Eaton.

Peggy Eaton was the lady in question during the Jackson administration. High society in Washington could not come to terms with her past, and the fallout from this rejection led to the disintegration of the president’s cabinet.

At one point during the dispute, Secretary of War John Eaton brandished a loaded pistol and began wandering the streets of Washington, threatening to duel with anyone who dared insult his wife.

3

. BLACK FRIDAY (1869)

U. S. Grant’s eight years in office were so mired by corruption that they were dubbed the “Era of Good Stealings.” Part of the problem was Grant’s practice of doling out government jobs to relatives and Union veterans regardless of ability, leading one senator to call the administration “a dropsical nepotism swollen to elephantiasis.” Had Grant surrounded himself with better men, he might not have been susceptible to the likes of Jay Gould and “Jubilee Jim” Fisk.

97

Two Wall Street speculators in their early thirties, Gould and Fisk owned the expansive Erie Railway, a conglomerate they had wrested from Cornelius Vanderbilt. In 1869, they set their sights much higher and schemed to corner the U.S. gold market with the help of anyone who had influence with the president.

98

The plan was to purchase as much gold as possible, driving up the price, while simultaneously preventing the government from selling its reserves. Once the market could no longer sustain the inflated value, Gould and Fisk would sell all of their holdings and make a hideously huge profit. The flooded market would consequently plummet, ruining anyone else who had invested in the precious metal.

With their plot underway, they tried to ensnare Washington insiders—bankers, a secretary to the president, even the first lady. No one was biting, except Grant’s brother-in-law, Abel Rathbone Corbin. Grant had known the sixty-seven-year-old Corbin for decades, but the president was unaware he had recently accepted a free “loan” of ten thousand dollars from Gould and Fisk.

As the summer of ’69 wore on, Corbin orchestrated several seemingly innocent meetings between his presidential brother-in-law and Gould and Fisk, who in idle conversation attempted to indoctrinate Grant on the wisdom of high gold prices. At the same time, they asked if he was about to release gold reserves anytime soon. Through all of this, Grant remained silent, but he did enjoy visiting Corbin’s posh New York home and traveling on Fisk’s luxury steamboat.

99

By September, gold certificates were climbing from $130 to $138 then $144 per share. Foreign imports and exports, payable only in gold specie, virtually stopped. Banks, which conducted most of their major transactions via the precious metal, could not conduct business. Gould and Fisk’s hoarding was pushing the entire economy to the brink. Then came September 24—Black Friday.

That morning, scarce certificates were rising by the hour: $150, $155, $160. Gould and Fisk owned $100 million worth, and they were making millions more with each passing moment. Finally realizing what his newfound friends had done, Grant torpedoed their scheme by dumping tons of treasury gold on the market. In minutes, the price collapsed to $133.

Unfortunately, the president’s intended targets emerged relatively unscathed. Gould had quietly sold a part of his holdings while buying smaller amounts, keeping up appearances. Fisk lost millions but still had his original fortune. Though indicted, both men paid handsomely for the finest lawyers and walked. As for the rest of the country, stock prices fell 20 percent across the board as jittery traders avoided investing. Grain prices dropped more than 30 percent in the face of unstable currency. Many greedy speculators and totally innocent farmers lost everything they had.

100

A congressional committee investigated the Gold Panic of 1869, and despite allegations that the president and the first lady were heavily involved, the panel absolved the Grants of any wrongdoing. The chairman of the committee was Union veteran James Garfield.

4

. THE WHISKEY RING (1874–75)

Tax evasion is as old as the Republic, especially when it comes to taxed liquor. To defray the cost of defending the colonies during the French and Indian War, the British Empire imposed a tax on colonial production of rum. Activists like Samuel Adams protested, and importers such as John Hancock turned to smuggling. When the American Revolution saddled the country with debt, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton put a duty on hard alcohol. In response, frontier distillers in Pennsylvania fomented the W

HISKEY

R

EBELLION

.

The grotesquely expensive Civil War caused authorities to once again impose a levy on alcohol. Once again the masses resisted, yet this time they were joined by members of the government.

To legally sell their wares, distillers and bottlers had to pay exorbitant fees that often cost many times what their product was worth. Poorly paid civil servants, assigned to the unpleasant task of enforcing the hated law, became targets of hostility from buyers and sellers alike. Rather than resort to violence, the opposing sides often formed small alliances, especially in the brewery capitals of Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Louis. In exchange for modest bribes, revenue collectors sold tax stamps far below price, greatly underreported factory outputs, and failed to report shipments. In St. Louis alone, approximately two-thirds of all alcohol went untaxed.

101

In 1874, Benjamin Bristow, the newly appointed secretary of the Treasury Department, began digging into rumors of wholesale corruption. With President Grant’s blessing, Bristow proceeded to clean house across the Midwest, confiscating record books, seizing ledgers, and closing down whole factories. More than 350 indictments were issued. Some of the guilty worked at the highest levels of the Treasury Department and the Internal Revenue Service.

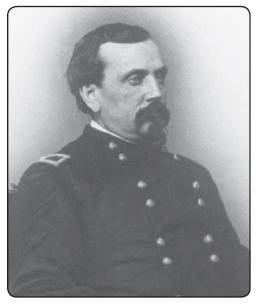

Orville Elias Babcock was a West Point graduate, an engineer, and a Union officer. He served at the siege of Vicksburg and worked as Grant’s aide-de-camp from the Wilderness campaign onward. As President Grant’s private secretary, Babcock was implicated in the Whiskey Ring but was eventually acquitted. Upon his death, he was interred at Arlington National Cemetery.

“Let no guilty man escape,” insisted Grant—until the trail led to the White House. Bristow had uncovered circumstantial evidence connecting a ringleader in Missouri to Brig. Gen. Orville Babcock. The likable Babcock had served with Grant and was one of the officers present at Robert E. Lee’s surrender at the McLean house in Appomattox. His current occupation was just as prestigious. He was the president’s personal secretary.

102

Sensing that Bristow had joined some Democratic smear campaign, Grant stoutly defended his comrade. He also launched an independent inquiry and offered to personally testify at Babcock’s trial.

In the end, his secretary was acquitted of all charges. But the pervasiveness of corruption in his administration, which was evident from his first to his last years in office, all but confirmed Grant’s own guilt of negligence in running the government. Because of the multiple scandals, many historians rank Grant’s presidency as a failure.

103

In order to spare his friend from further accusations, Grant reassigned Orville Babcock to be a federal inspector of lighthouses. Years later, while performing his job along the coast of Florida, Babcock fell into the sea and drowned.

5

. TEAPOT DOME (1922–24)

One of President Warren Harding’s closest poker buddies was Interior Secretary Albert Fall, a gun-toting, backslapping, face-punching cowboytype who first befriended Harding when they were both freshmen in the Senate. New Mexico’s first senator, Fall had made a name for himself as a defense lawyer specializing in adultery and murder cases. Florence Harding took an instant liking to him.

104

Though the president was a cretin to his wife, he was an otherwise friendly man, outgoing, and rather needy. He trusted easily and therefore saw nothing suspicious when Fall asked to have certain oil fields officially transferred from the Navy Department to his Interior Department, such as the Teapot Dome field in Wyoming. The president also obliged when Fall sold drilling rights to those areas to a select few poker guests, such as Harry Sinclair, a multimillionaire oil tycoon (and founder of Sinclair Petroleum).

105

Legislators became concerned when Fall made no attempt to entertain competitive bids from other companies. Inquiries initially turned up nothing. But then it was discovered that Fall had received a one-hundred-thousand-dollar “loan” from his oil associates. After years of formal investigations, the U.S. Senate Committee on Public Lands unearthed a number of gifts in livestock and cash to the senator, totaling nearly a half-million dollars.

After years of formal hearings, the U.S. government eventually regained the drilling rights plus some six million dollars in lost oil revenues, a fraction of what had gone into the pockets of Fall and his associates. Sinclair was found guilty of contempt and jury tampering, for which he served three months, while Fall was convicted of bribery and spent a year in prison, making him the first-ever sitting cabinet member to be convicted of a crime.

106