History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (59 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

Part of the job is mathematic—tracking vote counts, calculating the required majorities, determining margins of error. It also requires teaching skills—explaining to lawmakers the wisdom of voting a particular way, keeping cabinet members and senior staff informed on the personalities and issues involved. Sometimes, it involves playing Santa Claus—offering support for pet projects, sending invitations to White House functions, and the ultimate prize, scheduling face time with the president.

Typically, the work gets harder as the administration ages. Presidents start off with a high level of political capital in Congress, but this honeymoon invariably ends, and the legislature rediscovers a sense of independence. Conditions only get worse after midterm elections, when voters get impatient. The party of the incumbent almost always loses seats (thirty-three out of thirty-seven times since the Civil War). Consequently, no matter how hard the liaisons and the president try, they almost always see a decline in support. Eisenhower was getting 89 percent of his preferred legislation passed in his first year and only 65 percent in his last. Nixon went from 74 percent to 60 percent. Reagan fell from 82 to 47 percent over the course of his administration. The Democratic darling Clinton initially won nearly 90 percent of his favored bills, only to see his poor management of the White House damage his credibility. Some months he was only getting 30 percent of his bills passed.

90

During the Clinton administration, one of the many interns in the Office of Legislative Affairs was Monica Lewinsky.

9

. DIRECTOR OF THE NATIONAL ECONOMIC COUNCIL

It used to be that the president received most of his fiscal advice from a dream team of economists, many of whom were professors on loan from prestigious universities. A three-person panel with a support staff of a dozen fellow academics and statisticians, they focused on the long term, delving into macroeconomic issues of unemployment, inflation, debt, and taxation. This Council of Economic Advisers still exists, but its influence has waned since the 1990s. Now the practice is to think in much shorter terms and follow the lead of business advisers in the National Economic Council.

Created by Bill Clinton in his first week as president and headed by investment banker Robert Rubin (formerly of Goldman Sachs), the NEC was the financial equivalent to the N

ATIONAL

S

ECURITY

C

OUNCIL

, grouping together several cabinet secretaries and federal agencies, including the old economic advisers. Members included the secretaries of agriculture, commerce, energy, housing and urban development, labor, and transportation, the U.S. trade representative, the head of the Environmental Protection Agency, and others. The NEC was given the responsibility to not only formulate policy but to force it into action, demanding the cooperation of otherwise disparate and often competing offices. The council itself is armed with a staff of thirty and views domestic and internal trade policy in more concrete terms—such as housing markets, Medicare and Medicaid, Social Security, existing trade agreements, and tax laws.

The formula appeared to work. Concentrating on microeconomics instead of macroeconomics, the short-term stimulus packages and resulting growth in the economy signaled an end to a recession that had begun in the previous presidency. For three years in a row, the government operated in the black, and the NEC had the unusual pleasure of contemplating what to do with an annual budget surplus. Assuming as many did that this economic trend would continue for years to come, Clinton declared his NEC “the single most significant organizational innovation that our administration has made in the White House.”

91

George W. Bush tacitly agreed. A businessman himself, Bush favored the NEC over the Council of Economic Advisers. In his West Wing, he gave first-floor office space to the director and deputy director of the NEC, while the economic advisers worked far off-site, and were left understaffed for much of Bush’s second term. In 2011, Barack Obama went back to a successful team to find his economic leading man. Gene Sperling had been the NEC director under Bill Clinton when the federal government last saw a yearly surplus.

George W. Bush’s third director of the National Economic Council was Allan Hubbard. The two men were classmates in Harvard Business School, and Hubbard later became one of Bush’s major campaign contributors.

10

. DIRECTOR OF THE OFFICE OF MANAGEMENT AND ADMINISTRATION

The power is indirect. The Office of Management and Administration has no policy-making powers whatsoever, and yet every building and every human body in the White House complex completely depends upon it to operate smoothly.

With one of the largest employee bases in the Executive Office system (more than two hundred full-time staff members), it has quite a few ongoing assignments, such as keeping all computer and communication equipment updated and working, controlling the EOP budget, processing thousands of White House visitors each day, and acting as White House liaisons to the Secret Service. They are also in charge of salaries, building maintenance, staff orientation, the travel office, telephone operators, the motor pool, and the White House intern program. Arguably one of the most difficult of duties involves distributing limited West Wing office space to a legion of type-A personalities. The prime real estate is on the first floor with the Oval Office, followed by the second story and the basement (where the OMA director and deputy are usually located).

92

Created by Carter, streamlined under Reagan, and receiving its current title from George H. W. Bush, it is usually the least partisan office in the White House complex. If its workload was not ample enough, it also oversees the White House Military Office. With more than two thousand full-time and part-time employees, the Military Office handles the operations for

Air Force One

, the

Marine One

helicopter squadron, the 221 acres of Camp David (managed by the navy), the West Wing mess (also under the navy), the White House Medical Unit (twenty doctors and the president’s personal physician), honor guards, the Marine Band, plus five military aides (all lieutenant colonels or higher) that carry the “Football”—the briefcase that contains the launch codes for U.S. weapons of mass destruction. On top of it all, the Office of Management and Administration also determines who gets the best parking spots outside the West Wing.

93

Indicative of their vital position in presidential operations, OMA directors are paid almost the same as the chief of staff.

Corruption comes in a multitude of genres—blackmail, graft, insider trading, espionage, sex. It mostly resides in the lower depths of society. The higher it ascends, the greater the scandal when it surfaces.

In examining instances of executive intrigue, a few observations can be made. Generally, citizens hold their leaders to a higher ethical standard than themselves. They may or may not care for a particular president, but as a whole, the electorate holds the presidency in high regard, and the public wrath has been most pronounced when office-holders do not express similar respect.

Also, the populace will seek retribution, to a point. When implicated, the president in question must offer disclosure, accept responsibility, or suffer a certain amount of humiliation. Once the public appetite for reprisal has been satiated, regardless of the letter of the law, forgiveness pervades, and political capital is gradually reinstated. If the nation ever wanted to adopt a new motto that best reflects its basic nature, it would do well to consider Ronald Reagan’s favorite proverb: “Trust, but verify.”

Lastly, as the following cases clearly illustrate, the executive branch has been generally inept at engineering conspiracies. Subject to the watchtowers of free speech and free press and populated with rivals, rogues, saints, and squealers, the White House consistently fails to hide so much as an office breakin without half the planet eventually hearing about it. Below in chronological order are the worst episodes of political scandal that directly involved the executive branch, measured by the number and illegality of acts committed and their measurable consequences.

1

. XYZ AFFAIR (1797)

During the French and Indian War, the colonies sided with Mother England. Fifteen years later, rebellious Americans paired up with the French to shun the British yoke. Fifteen years after that, the United States became chummy trade partners with Britain again.

Not surprisingly, Paris found this two-step rather tiresome. In 1796, French magistrates and media reminded the Yanks that it was France who came to the rescue during their little revolution, signing a treaty of eternal cooperation and eventually providing most of their ammunition, gunpowder, and navy. At Yorktown, half the troops were from

l’armée française

. In rebuttal, many Americans, including President John Adams, reminded the French that the Treaty of Alliance applied to the France of Louis XVI, and that particular head of state had been chopped off years ago.

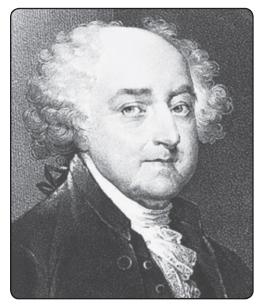

John Adams tried to invoke executive privilege in the XYZ Affair. His prudence initially caused a national crisis but ultimately led to his vindication.

Battles in print soon turned to seizures on the high seas, as French privateers began confiscating American ships by the dozen. Hoping to calm the swelling tempest, Adams sent Charles C. Pinckney, John Marshall, and Elbridge Gerry to Paris on a mission of peace. Greeting them were three dignitaries who said they would let the Americans speak with the French foreign minister, providing the Adams administration pony up $250,000, plus a loan of $10 million, and a formal apology from Adams himself for his chides against the French people. It is unlikely the demands were serious, and they would remain secret, for a while.

When the American public heard that the mission had failed, those sympathetic to the French (including Vice President Thomas Jefferson) accused Adams of sabotaging the negotiations, and they demanded to see all the records pertinent to the case. Adams claimed executive privilege and refused, which only cemented suspicions. Grudgingly, the president released the sordid details to the Senate, and someone leaked the news to the public. The French and their blackmail, slurs, and affronts—it was all there in ink and parchment. The only unknowns were the names of the French diplomats, who were simply called X, Y, and Z.

Red with rage, the pro-British majority called for an immediate declaration of war. Congress appropriated millions for warships, coastal forts, and a larger army. Cities began to collect money to build gunboats. The undeclared Quasi War ensued, which dragged on precariously for two years, costing the lives of at least twenty American sailors and terminating all existing treaties between the two countries. The scandal, which initially threatened to destroy Adams’s credibility, ultimately made him look like a sage and inspired Congress to pass the dictatorial A

LIEN AND

S

EDITION

A

CTS

.

94

Hundreds of merchant vessels were captured by both sides during the two-year Quasi War. As a result, insurance rates for overseas shipping went up nearly 500 percent.

2

. THE PETTICOAT AFFAIR (1828–31)

The president’s cabinet is sometimes called the official first family, and as with any household, the children will squabble from time to time. For Andrew Jackson’s administration, one fight involved a woman who some deemed unworthy to include. The resulting fight sent nearly the entire clan packing.

She was extroverted and sociable Margaret O’Neale, who had a spouse in the navy. Washington gossipers claimed she also had a lover in the Senate, John Henry Eaton, a friend of Andrew Jackson. Saucy stuff. Then in 1828, news came that Margaret’s husband, while serving at sea, took his own life. By custom, Margaret was supposed to mourn for a year. She decided not to wait, and she married her alleged lover. Barely two months after that, newly elected President Andrew Jackson named Eaton as his secretary of war.