History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (61 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

Warren Harding once said, “If Albert Fall isn’t an honest man, I’m not fit to be President of the United States.”

6

. THE VETERANS BUREAU SCANDAL (1923)

Harding’s wife, Florence, had a cold streak ten miles wide, but she was empathetic to the downtrodden, especially victims of abuse. Herself beaten as a child, and later impregnated and abandoned by an alcoholic first husband, she found love in a second marriage, until he cheated on her—repeatedly. Some solace came when he became president in 1920, enabling her to act as a guardian to the powerless.

Of her many causes, Mrs. Harding was most devoted to “her boys,” three hundred thousand disabled American veterans of the Great War. She would visit area wards and hospitals, host picnics for the wounded, support charity events, and champion their cause within the White House. When her husband’s industrious friend Charlie Forbes became head of the Veterans Bureau, Florence was understandably elated. He was a retired colonel and Distinguished Service Medal recipient. Under Forbes’s direction, the bureau quickly spent thirty-six million dollars on new hospitals, distributed medicines and supplies to survivors in need, and oversaw the well-being of millions of former doughboys. Oddly though, his accomplishments were only showing up on paper.

Suspicions arose when Forbes, who made a modest ten thousand dollars per year, began to hold swank parties at lavish venues and developed a penchant for high-stakes gambling. Investigations soon unearthed multiple cases of kickbacks from unscrupulous contractors. Manifests showed the government paying twenty times the market price for a century’s worth of cleaning supplies. Millions of dollars’ worth of blankets, sheets, gauze, pajamas, alcohol, and drugs were being classified as “surplus” or “damaged” and sold to private buyers for next to nothing. So incensed was the president by the level of betrayal that he invited Forbes to the White House, called him into the Red Room for a chat, and proceeded to choke him.

107

Florence Harding’s advocacy for veterans included welcoming Confederate veterans to the White House in the summer of 1922.

While the Senate commenced official hearings, Forbes resigned and left the country. It was soon discovered that, along with being a thief, Forbes had never served in the First World War. He had deserted the army in 1914. He also had a history of spousal abuse. For his shameless graft, which cost the government millions and caused undue suffering upon thousands of disabled veterans, Charles Forbes was eventually fined ten thousand dollars and sentenced to several years in prison. He was released after serving eighteen months.

108

Forbes’s legal adviser Charles Cramer, who was also involved in the Veterans Bureau scandal, committed suicide before he could be tried. He took his own life in the very home he bought from a couple named Warren and Florence Harding.

7

. THE CORRUPT SPIRO AGNEW (1973)

The vice presidency has seen two resignations, and John C. Calhoun did so because he could no longer tolerate the authoritarian Andrew Jackson. The other retiree had few options but to leave. It was either that or prison.

In April 1973, Dick Nixon enjoyed an approval rating of 60 percent, but he suspected it would fall as more information about hush money, wiretaps, and a certain burglary began to point toward the Oval Office. When his vice president expressed concerns about an investigation in Maryland involving construction contracts and bribery, Nixon dismissed the comment as irrelevant.

By May, Attorney General Elliot Richardson discovered why Agnew, the former governor of Maryland, was so worried about an innocuous inquiry about alleged kickbacks. Agnew was involved—heavily. The head of the Justice Department claimed to have never seen such damning evidence, speculating that the vice president could be indicted on at least forty counts. Nixon believed there was modest cause for concern, but he had his own worries. The FBI was beginning to deploy agents within the White House to monitor the movement of documents and staff.

109

By August, the entire ship of state was foundering. Nixon’s ratings were down to 31 percent, carpet bombing in Cambodia was having no effect on the influx of enemy troops into South Vietnam, and the public was becoming aware of the White House tapes. On top of it all, the

Wall Street Journal

exposed the extent of Agnew’s probable crimes in Maryland, including extortion, kickbacks, tax evasion, and bribery. Information arose that he was still receiving dirty money. To Nixon’s face, Agnew denied the allegations, and he repeated his statements in a news conference soon after. The public support for the popular veep was overwhelming.

110

But so was the evidence, and Agnew could no longer hide it. In October, he agreed to plead no contest to one count of tax evasion, pay a fine of ten thousand dollars, and serve three years’ probation. He would also step down from the vice presidency on October 10, 1973. When he broke the news to Nixon, the two men shook hands, parted company, and never said a word to each other for the rest of their lives.

111

Two months after Spiro Agnew’s resignation, Gerald Ford was confirmed as the vice president. In the interim, the line of presidential succession temporarily passed to Speaker of the House Carl Albert—a Democrat.

8

. WATERGATE (1972–74)

Interviewed years after the fact, former president Gerald Ford concluded, “If Nixon had destroyed the tapes, there would have been no solid, concrete evidence of a cover-up.” Ford was incorrect on two counts. Had Nixon attempted to obliterate the tapes (improbable since the Secret Service possessed them), the act itself could have constituted an obstruction of justice. In addition, recordings or not, the conversations on them still took place, and every participant was a witness.

112

Among them was H. R. “Bob” Haldeman, Nixon’s former

CHIEF OF STAFF

and one of the first to discuss the W

ATERGATE

breakin with the president. Nixon’s number-two man was John Ehrlichman, his assistant for domestic affairs and architect of T

HE

P

LUMBERS

, an outfit instructed to stop all White House leaks. Close behind was young legal counsel John Dean, with whom Nixon discussed bribing the five Watergate burglars and laundering the money they would receive. Then there was the Committee to ReElect the President (CREEP), including former attorney general John Mitchell, G. Gordon Liddy, who coordinated the breakin, and former CIA agent E. Howard Hunt, who had organized the wiretapping of the Democratic National Committee Office in the W

ATERGATE

building. And so on and so on.

Nixon neither authorized the burglary nor knew about it ahead of time, but the ensuing year found him scheming with the above cadre to block all investigations into the matter. Part of his downfall was his eagerness to find a scapegoat, even if it included the very people trying to protect him.

Month after month, conversations revolved around ways to quiet the burglars, impede the FBI, hide earlier wiretappings, collect hush money, and blame Mitchell or Hunt or the CIA. The sheer volume and complexity of Nixon’s efforts, more than any recorded conversation, was what condemned him to failure. By late summer of 1974, even Nixon acknowledged he had done the exact opposite of what he intended, making a bad situation far worse by attempting to cover it up. On the evening of August 8, in a televised address from the Oval Office, Nixon offered his resignation to the American public. They abruptly accepted.

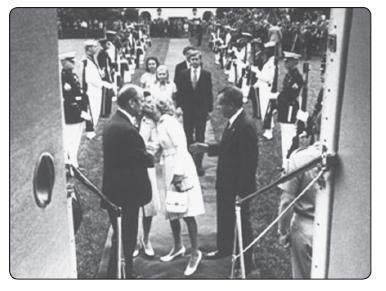

Richard and Pat Nixon prepare to board Marine One for the last time as president and first lady.

Nixon Library

Looking back at what had transpired, Gerald Ford was partially correct in emphasizing the impact of the infamous tapes because they revealed something as damaging as any testimony. Emanating from the thousands of hours of muffled static and pregnant pauses was the undeniably acidic nature of a profane, somewhat paranoid, and thoroughly manipulative individual who was willing to do virtually anything to stay in power. What Ford and many others failed to recognize, however, was that this man had risen to power

because

of his reputation for ruthlessness. He made a career out of publicly dismantling Democrats, vowing law and order on American streets, and acting as the toughest anticommunist since Joe McCarthy and Barry Goldwater. And for his imperial appeal, the American public reelected him in one of the biggest landslides in U.S. history, five months

after

a minor burglary in a Washington office building.

In total, twenty individuals either pleaded guilty or were convicted for taking part in the Watergate scandal. Their average maximum sentence—five years. Average time spent in prison—twelve months.

9

. IRAN-CONTRA (1985–87)

While the Carter administration struggled to free the Iranian hostages, candidate Ronald Reagan campaigned on a “tough on terrorism” theme. Once in office, the Gipper had just as much trouble liberating captives as Carter did. In Reagan’s case, Hezbollah was the perpetrator, and the Lebanese organization was in possession of several Americans, including journalists, clergy, government workers, and CIA Beirut chief William Buckley.

113

In contrast to the micromanaging Carter, Reagan simply instructed a few staff members, primarily N

ATIONAL

S

ECURITY

A

DVISER

Robert “Bud” McFarlane, to get the hostages out by any peaceful means available. Those means eventually involved breaking U.S. law.

The idea was to sell weapons to Iran, who in gratitude would supposedly instruct their ally Hezbollah to release the Americans. Acting in what might be described as good faith, McFarlane commenced the secret shipments in the summer of 1985 without a guarantee that anything would be done about the captives. The plan did not go well. Though hundreds of shoulder-fired rockets were sent, the scheme produced only one freed hostage, and it wasn’t CIA agent Buckley, the man the administration most desperately wanted back. In frustration, McFarlane resigned.

Third-level characters in Iran-Contra included (from left to right) Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger, Secretary of State George Schultz, White House Counsel Ed Meese, Chief of Staff Don Regan, and President Reagan.

Reagan Library

Replacing him was John Poindexter, who continued the program. Assisting him on the N

ATIONAL

S

ECURITY

C

OUNCIL

was Lt. Col. Oliver North, who suggested illegally channeling profits from the arms sales to a right-wing insurgency in Nicaragua. If the Iranian deal was not bearing results, reasoned North, at least the revenues could help combat leftist governments—a prime objective of the R

EAGAN

D

OCTRINE

.