History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (57 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina revealed a major shortcoming with the Situation Room. Configured for international emergencies, the complex was conspicuously lacking in domestic communications, greatly retarding its ability to gather information from and dispense instructions to sites within the United States.

MOST POWERFUL OFFICES IN THE WEST WING

Grover Cleveland called the presidency “a responsibility almost beyond human strength.” Novelist John Steinbeck observed, “We give the President more work than a man can do, more responsibility than a man should take, more pressure than a man can bear.” Gerald Ford’s

CHIEF OF STAFF

Dick Cheney said of every chief executive, “No matter how hard he works or how smart he might be, he can’t do it by himself.”

70

For decades, presidents tried to do it on their own because they had to. Congress used to keep the executive branch on a tight fiscal leash, providing almost nothing for administrative assistance. Consequently, Lincoln often worked sixteen hours a day. A typical shift for Benjamin Harrison and his cabinet was 9:00 a.m. to midnight. Herbert Hoover ate his meals in ten minutes or less so he could get back to work.

71

Finally showing some mercy, the legislature passed the Reorganization Act of 1939, establishing the Executive Office of the President (EOP) and doubling Franklin Roosevelt’s staff from forty to eighty. Considered by many scholars as the start of the “modern presidency,” the EOP should be called the beginning of the modern bureaucracy. The prime motivation, of course, was not to create a top-heavy paper mill but to expand federal services to satisfy voters. As the appetite of the populace grew, so grew the executive branch. William McKinley functioned with a staff of twenty-seven. William Clinton had more than three hundred full-time advisers and administrators. Add consultants, volunteers, security, and interns, and his total was closer to six thousand.

The Executive Office is a paradox in many ways. It is not one office but many. It allows a president to delegate busywork, yet it enables him to take on more responsibilities. The EOP provides greater control over the civil service, but it also adds one more layer to the bureaucracy. It is a product of democracy, yet most of its staff members “serve at the pleasure of the president” and are officially accountable only to him.

In this “White House community,” only a select group of directors and deputies are given precious office space in the West Wing. Consequently, they are among the few citizens who get consistent face time with the president. And in Washington, time equals power. Following are the ten people who commonly have the greatest amount of presidential access. As George H. W. Bush’s

PRESS SECRETARY

Marlin Fitzwater said, “You’re really talking about twenty people, a very small group…a very personal kind of thing.”

72

1

. CHIEF OF STAFF

When Harry Truman assumed the Oval Office, he was shocked by the chaotic nature of operations. Franklin Roosevelt thrived in the informal environment. Truman could not tolerate such discord and redundancy. Determined to transform the circus into a drill team, he hired former Labor Department specialist and FDR assistant John Steelman to be his “assistant to the president.” The title would soon become something more imposing—the chief of staff.

The Nixon administration produced perhaps the tightest inner circle ever to command the White House: (from left to right) President Nixon, Chief of Staff Bob Haldeman, international relations guru Henry Kissinger, and John Ehrlichman, assistant to the president for domestic affairs.

White House

The COS is the manager of the West Wing and gatekeeper to the Oval Office. Most any message, request, or problem must first pass through this guardian before it is deemed worthy of a president’s attention. In turn, orders from the top usually pass through the COS. As Gerald Ford saw it, “You need a filter, a person that you have total confidence in who works so closely with you that in effect he is almost an alter ego.” Commonly, a president meets every morning with the chief of staff and deputies before continuing with the rest of the day.

73

The power of the position depends heavily on the governing style of the president. Truman, Eisenhower, and LBJ preferred obedient lieutenants in their chain of command. As a way of staying in control, Nixon demanded absolute loyalty from H. R. Haldeman and later Alexander Haig and then proceeded to circumvent their authority at every turn. “I had these problems with Nixon; so did everyone else who worked for him,” said Haig. Rather than trust a single deputy, noticed Haig, the bowling president chose to play “six or seven alleys.”

74

Hands-on executives Ford, Carter, and Clinton initially tried to operate their office on their own and consequently experienced chronic inefficiency and infighting. They solved the problem by hiring assertive individuals to take control. Ford first turned to conservative hawk Donald Rumsfeld (future secretary of defense) and later to authoritarian Dick Cheney (future vice president). Clinton’s administration wandered for more than a year until Leon Panetta assumed the role of disciplinarian. When Erskine Bowles took over in Clinton’s second term, even Hillary needed an appointment to see the president.

75

The only recent president who never had a chief of staff was Jack Kennedy. To manage the West Wing, he preferred a “brain trust” of close colleagues rather than a single individual.

2

. DEPUTY CHIEF OF STAFF

The COS manages the office. Deputies are the chief advisers. The position is a relatively new invention, made to liberate the primary consultants from any other duties and prevent them from becoming highly visible lightning rods. In hindsight, Lincoln’s William H. Seward, Eisenhower’s John Foster Dulles, and Gerald Ford’s Henry Kissinger might have operated with more focus and less controversy if they had been deputized out of the spotlight. Instead, they worked in the very public position of secretary of state, where they had to juggle serving the president, managing an entire federal department, and catering to the press.

The first de facto deputy was John Ehrlichman, Nixon’s assistant for domestic affairs. Before W

ATERGATE

made him infamous, Ehrlichman worked in splendid anonymity, having round-the-clock access to the president while preventing others from having the same privilege. Ehrlichman and chief of staff H. R. Haldeman were so possessive of Nixon’s time that they were known inside the White House as “the Berlin Wall.”

More recent Republicans have moved toward multiple deputies as the central core of their administration. In his first term, Ronald Reagan entrusted much his policy making to COS James Baker III, deputy COS Michael Deaver, and White House counsel Ed Meese. George H. W. Bush often had two deputies, one for political strategy and the other for domestic policy. In his second term, George W. Bush added a third, designating high-school graduate Karl Rove officially as an additional deputy. In reality, Rove was the lead adviser of the entire administration.

Illustrating the growth of bureaucracy in the West Wing, chief of staff James Baker III, while working for George H. W. Bush, had two deputies under him, plus an executive assistant, an administrative assistant, a staff assistant, a special assistant, and a staff assistant to the special assistant.

3

. THE WHITE HOUSE COUNSEL

The attorney general is the nation’s lawyer. The White House counsel is the attorney for the executive branch. Established in 1943, the office has steadily grown in size and influence, reflecting an increasingly litigious political system.

Anything that is potentially a legal issue (which is everything) requires an examination from the counsel’s office. From hiring practices to war powers, pardons, ethics regulations, and executive orders, it all falls under their purview. Before a president or any cabinet member gives a major speech, this office will have gone through it line by line, looking for any statement that might constitute a breach of law. Before a president ever signs a bill, the counsels will ensure the act would in fact be legal. Before presidents claim executive privilege, they will usually consult with this group first to see if they have a case.

Armed with attorney-client privilege, in charge of preventing legal problems and solving them if they arise, chief counsels are frequently among the most trusted members of a president’s inner circle. Consequently, they hold a great deal of prestige in the eyes of their employer. The first official counsel, Samuel Rosenman, was also one of FDR’s key speechwriters. Truman’s confidant and the architect of his miraculous 1948 victory was Clark Clifford, who would go on to become a private attorney for Jack Kennedy and LBJ’s secretary of defense. Few people saw the honest side of Kennedy more often than his counsel Theodore Sorenson, the man who wrote much of his inaugural address and played a central role in the C

UBAN

M

ISSILE

C

RISIS

. Nixon involved John Dean in the most sordid elements of the W

ATERGATE

cover-up. Reagan’s White House counsel Ed Meese, and later attorney general, was like a second chief of staff.

76

When he was thirty-four, Fred Fielding had the distinction of serving as deputy counsel under John Dean during Watergate. He became lead counsel in his early forties for the Reagan presidency. In his later sixties, he returned as lead counsel for George W. Bush.

4

. NATIONAL SECURITY ADVISER

A product of the Cold War, the National Security Council was officially created by the National Security Act of 1947 (the same measure that made the CIA and the Department of Defense). The idea was to form a centralized command structure in place of the divergent State, War, and Navy Departments. Initially, the council met in the Old Executive Office Building, across the street from the West Wing.

Chaired by the president and vice president, its members included the secretaries of defense, state, and treasury. In consulting roles were the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the director of the CIA. A national security adviser acted as overall director. Truman thought the group unwieldy but turned to it often during the Korean War. Eisenhower was quite comfortable with its backroom feel, where politics and military concerns cohabitated. He attended nearly 90 percent of the meetings.

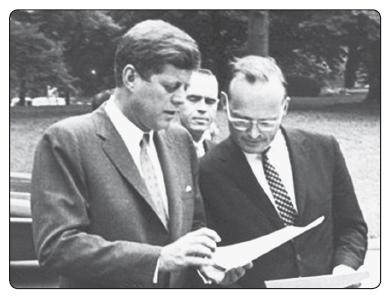

JFK confers with National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy, a major advocate for increased involvement in Vietnam.

Abbe Rowe, National Park Service