History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (55 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

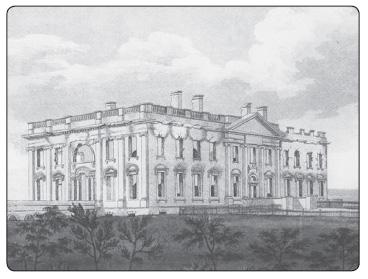

James Hoban’s design for the White House was based heavily on an existing mansion in Ireland called the Leinster House, which today is home to the Parliament of the Republic of Ireland.

2

. THE BURNING (1814)

The true White House lived but fourteen years, only to become one of thousands of buildings destroyed during the War of 1812. When American soldiers set fire to the Canadian city of York (later Toronto), British troops advanced up the Potomac to execute revenge upon Washington. Chasing American soldiers and militia from the city streets, redcoats entered 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue and proceeded to ransack the place, tossing furniture and breaking glass. They stole silverware, clothes, paintings, and James Madison’s love letters to his wife. After raiding the wine racks and toasting the deposed president, the officers and enlisted filed outside to throw torches through the tall pane windows. In minutes the entire building was aflame, matching the hundreds of house fires rising throughout much of the city. Citizens could see the glow of their burning capital from thirty miles away.

58

Separated during the melee, James and Dolley Madison would not find each other for two nights, reuniting at a place called Wiley’s Tavern, Virginia. When they returned to their abandoned home days later, all that remained were most of the four main outer walls and a few chimneystacks. Madison would serve the remainder of his term living in various homes nearby, but he and many others began to contemplate moving the Federal City for a fourth time, perhaps to Ohio, where it would be safer from foreign intrusions.

59

After the British burned the city in August 1814, all that remained of the White House was a fire-gutted shell. Ensuing months of rain and snow further deteriorated the charred stone walls.

The government decided to stay, and Madison aimed to rebuild the Executive Mansion to its original specifications, rehiring James Hoban to repeat his most famous work. The project did not begin until the war was fully over in 1815, by which time rain and snow had further deteriorated the shell.

It took nearly a year to clean out the charred debris and reconstruct the roof. By March 1817, white lead paint coated the stone exterior and most of the floorboards were in place as James Monroe took the oath of office within sight of the recovering mansion. He would finally move into the building later that year, but work would not be completed until 1820. In what would become a tradition for Washington, D.C., reconstruction took longer than expected, and it went 60 percent over budget.

60

Britain’s act of arson totally consumed the White House roof. Much of the new roofing material, consisting of copper and slate, ironically had to be imported from Britain.

3

. TWO PORTICOS AND MANY DREAMS UNREALIZED (1824, 1829)

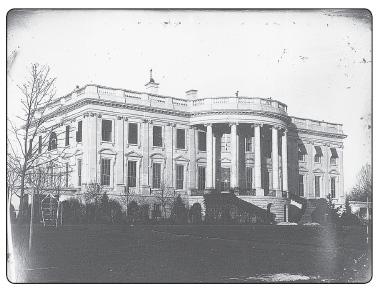

If the political will and necessary funds had been available, the White House would have looked far different than it does. The Monroe administration initially wanted to double the width of the building, but a nationwide financial panic in 1819 delayed those plans indefinitely. In his last year in office, Monroe opted for something more modest—a rectangular portico to the north side of the building. Two presidencies later, Andrew Jackson took pity on journalists waiting outside in the rain and added a curved portico to the south-side entranceway in 1829. For the ornate stonework, he borrowed Italian artisans working on the ever-expanding Capitol to the east. These two grand awnings would be the last significant changes to the face of the complex for nearly a lifetime.

In the 1880s, Chester Arthur wanted to tear the whole structure down and start anew. After sixty years, the house was showing structural and aesthetic signs of weakness, primarily from the piecemeal reconstruction performed during the Madison-Monroe years. Comparing the expense of needed repairs to the lower cost of a new building, Arthur lobbied for the latter. A depleted treasury assured him that even minor renovations were not possible, and the poor structure continued to age.

61

The South Portico, added in 1829, enhances this c. 1846 image of the White House. During the Truman restoration, a second-story balcony was added.

In 1890, the Benjamin Harrison family, all thirteen of them, felt immobilized by the growing number of staff workers carving out office space on the family’s second floor. First Lady Caroline Harrison envisioned tripling or quadrupling the floor space, and she collected prospective designs from various architects to make the dream a reality. One of her favorite sketches proposed two grand wings extending from each end of the main building, with three-story domed rotundas anchoring both sides. Another popular plan called for the creation of a great quadrangle, with the existing structure acting as the south side. The Harrisons requested an initial investment of $950,000 to get started; Congress gave them $35,000 for minor renovations.

62

During her scaled-down renovating, Caroline Harrison came across discarded White House china in an old cabinet. Adding to the set herself, she began the tradition of displaying past china patterns to visiting tourists.

4

. THE ROOSEVELT RECONSTRUCTION AND THE WEST WING (1902)

Over the course of the nation’s first century, as the number of executive employees increased, their offices began to encroach onto the second floor where the first family resided. This was not a major issue for childless William and Ida McKinley. But their successors, the larger-than-life Roosevelt family, found the accommodations untenable. The house itself was also beginning to protest, with peeling wallpaper, foot-worn carpets, and kitchens glazed with decades of hardened grease. The floors visibly sagged. Every time there was to be a large gathering in one of the main areas, carpenters had to construct temporary buttressing in the rooms below.

63

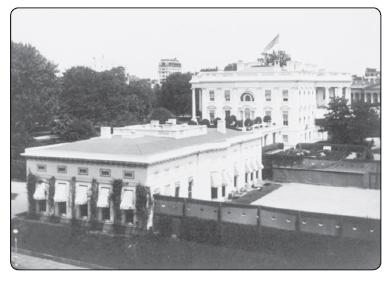

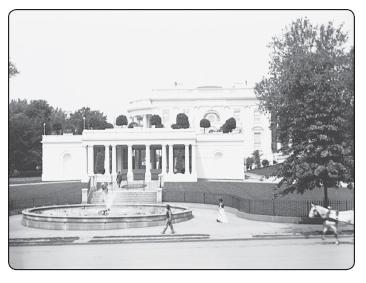

Theodore Roosevelt’s new office space, as seen in this 1909 photograph, has since become known as the West Wing.

This 1909 image shows the East Wing before the structure became a building in its own right in the 1940s—complete with bomb shelter.

To correct the problems, TR commandeered the services of New York architectural firm McKim, Mead, and White. Charles McKim directed the effort in person. Typical TR, he gave his architects months, not years, to get the work done.

Inside the house, exposed pipes were tucked behind the walls, unneeded partitions were removed to create open space, bright white paint and natural woods lightened the very air of the once-dank structure. The house began to resemble the presidency and the country itself, shedding the dark and compartmentalized past for the open view of modernity.

Outside, large greenhouses flanking both sides of the building were torn down. Intended to supply the White House with fresh flowers year-round, they gave the wings a cluttered look and masked the long, elegant colonnades built during the Jefferson administration. A public entrance was added to the end of the east colonnade. On the west side, an entirely new one-story building emerged, connected to the house by the west colonnade gallery. Containing telegraph and telephone offices, the Cabinet Room, a press area, the mail room, a reception area, and TR’s main office, the complex successfully siphoned away the staff and busywork from the elegant main house.

Though built in 1902, the office building wasn’t commonly called the West Wing until the 1930s.

5

. THE 180-TON ROOF (1926–27)

During the constructing of the West Wing, crews also expanded the State Dining Room in the main residence by knocking out a dividing brick wall. The end result was stunning. The expanded room resembled a grand lodge, with rich green carpets, deep velvet drapes, and moose and elk heads staring down on the spacious hall. Unfortunately, the wall that was removed turned out to be load-bearing.

Years later, during the Coolidge administration, the missing wall’s importance became evident when the full weight of the ceiling began to crack the wooden support beams. Informed that the roof had become unsafe, penny-pinching Calvin Coolidge suggested that if it was truly unstable, it would have already fallen down.

Credit Grace Coolidge, the more aggressive spouse, for showing initiative. She recommended solving both the structural problem and the building’s chronic lack of space by adding a third floor. Congress consented to her wisdom and granted the money. Renovators tore apart the decaying attic area, lowered the floor, increased the pitch of roof, and replaced aged lumber beams with reinforced steel and concrete. Skylights illuminated the hallways, and an electric elevator was installed. In all, eighteen rooms were added, providing much-needed space for guests, servants, and storage. Crews also constructed a new room for the first lady, a sunroom that offered a majestic view of the south grounds and the slow-rolling Potomac River beyond.

64

An engineer who helped design the White House roof reconstruction was Ulysses S. Grant III, grandson of the eighteenth president.

6

. WEST WING RENOVATION AND THE FINAL OVAL OFFICE (1933–34)

The eminent chamber of the executive branch, the Oval Office did not exist until the twenty-seventh presidency, when William Howard Taft had an internal rectangular room converted into an ellipse in 1909. Emulating the grand oval rooms of the White House’s south side, the shape also served as an homage to George Washington, who preferred curved walls for formal reception rooms. The shape allowed for a natural balance, where the president could stand at one center of the room and the people the other, symbolizing the two sources of American governance.