History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (26 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

Initially he hoped to reduce the losses by cutting into the solidly entrenched entitlements to the American public. But a Democratic Congress resisted, opting instead for a raise in revenues. To keep the government in operation, Bush agreed to raise taxes—in violation of his 1988 vow never to do so. The strategy worked, partially. For the first time ever, the U.S. Treasury received more than one trillion dollars in receipts in 1990. But expenditures also reached a record high, surpassing $1.25 trillion for the year.

When Medicare was established in 1965 to offer health coverage for the elderly, its projected cost was supposed to be less than $10 billion by 1990. The price tag for the Bush administration in 1990 ended up being more than $100 billion.

10

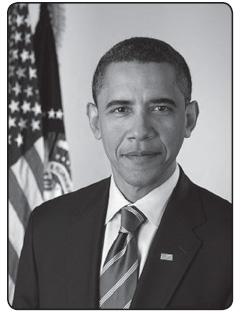

. BARACK OBAMA (47.8%)

NATIONAL DEBT IN 2009: $11.88 TRILLION

NATIONAL DEBT IN 2013: $17.55 TRILLION

In the first year of his presidency, Barack Obama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, despite the fact that he had not engineered any major peace initiatives; was commander in chief of the most powerful military force on Earth; and was heading two major wars. The prize committee may have intended the medal to be a veiled critique against his predecessor George W. Bush as much as an endorsement of Obama’s inaugural vow to choose “hope over fear, unity of purpose over conflict and discord.” Regardless, when Obama accepted the honor in December of 2009, the financial cost of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars had exceeded $750 billion and was still climbing, as was the annual defense budget of over $636 billion. By 2011, the Pentagon received more than $678 billion annually. Unquestionably, global hegemony required hefty outlays, but Iraq and Afghanistan had become the first and second longest wars in American history, and while most of the defense budget was anticipated, the two conflicts were financed primarily through borrowing.

35

When Barack Obama was born in 1961, the average federal deficit was approximately $6 billion per year. Right before he became president in 2009, the deficit exceeded $6 billion per week, a trend he would fail to break.

U.S. military presence in Iraq ended in December 2011, allowing for some optimism that the rising debt would slow. But a continuing recession kept federal revenues growing at a much slower rate than expenses. A wave of major corporate bailouts, extensions of tax cuts, plus record numbers of citizens on Medicaid, unemployment insurance, and other programs prompted extensive debt spending for the second administration in a row (see C

OMMONALITIES

B

ETWEEN

B

USH AND

O

BAMA

).

One major factor was also in play, a good problem that plagued many twenty-first century Americans. Generally speaking, they were living relatively long lives in an age of rapidly advancing medical technology. When FDR’s “New Deal” began Social Security payments to the elderly in 1940, the average lifespan was 57. By 2010, the average lifespan had surpassed 78. When LBJ’s “Great Society” brokered Medicare in 1965, computed tomography or “CAT” scans, heart bypass grafts, heart transplants, and vaccines for chicken pox, meningitis, mumps, pneumonia, and rubella did not yet exist. Though Obama, at age 47, was the fifth-youngest person to become U.S. President (behind Theodore Roosevelt, Kennedy, Clinton, and Grant), he served an aging and increasingly expensive population. By 2012, the federal expense of Social Security and Medicare alone exceeded $1.3 trillion annually.

36

During the Obama administration, the amount of money spent on the interest toward the national debt exceeded the budgets of NASA, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Justice Department, the National Science Foundation, the State Department, and the Veterans Administration combined.

Woodrow Wilson called it a president’s “most formidable prerogative.” The less eloquent Harry Truman considered it, in relation to Congress, “one of the greatest strengths that the president has…if he doesn’t like something that

they’re

cooking up.” Latin for “I forbid,” the word

veto

does not appear in the Constitution, yet it exists as one of the most recognizable expressions of executive authority.

37

When the 1787 Philadelphia Convention schemed to form a more perfect Union, delegates quickly endorsed the concept of a “qualified negative.” New York’s Alexander Hamilton and Pennsylvania’s James Wilson favored an absolute veto. In opposition were Virginia’s George Mason and Pennsylvania’s Benjamin Franklin, the latter insisting that if one person could completely override a legislature, “the Executive will always be increasing here, till it ends in a monarchy.”

38

James Madison argued convincingly for a middle ground. Congress should have the option of overriding, he said, but a veto was essential to prevent some “popular or factious injustice.” His plan carried the day, with a subtle wrinkle—the pocket veto. If Congress adjourned within ten working days of submitting a bill, a president could simply not sign it, in essence making his rejection absolute.

To avoid appearing despotic, early presidents rarely employed it. Washington denied only two bills, both on grounds of their constitutionality. John Adams and Thomas Jefferson didn’t block any. Those who tried were often rebuffed. In 1834, the Senate censured Andrew Jackson for his virulent refusal to recharter the Bank of the United States. For his ten vetoes, John Tyler was nearly impeached by the Twenty-Seventh Congress, which accused him of “withholding his assent to laws indispensable to the just operations of the government.” Franklin Pierce and Andrew Johnson saw the majority of their vetoes overridden (five of nine and fifteen of twenty-nine, respectively).

39

Gradually, executives asserted themselves against Congress, and overrides became rare. A few presidents went undefeated (none better than William McKinley at 42–0), and most enjoyed a 95 percent success rate. Of more than twenty-four hundred vetoes, slightly over one hundred have failed to carry through.

Below are the ten most prolific presidents in the use of the qualified negative, ranked by the total number of their official rejections. Reflecting the growing power of the executive branch, eight of these ten administrations are from the twentieth century.

40

1

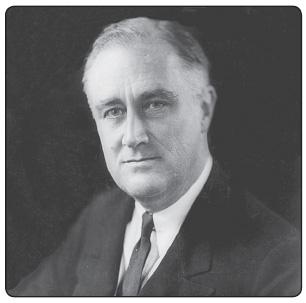

. FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT (635)

REGULAR VETO: 372

POCKET VETO: 263

OVERRIDDEN: 9

For some, the veto is a paring knife to shave away excess pork fat. For others, it is an axe to chop whole programs. For Franklin Delano Roosevelt, it was the dress sword, a symbol of authority over Capitol Hill.

In twelve years, Roosevelt never faced a house in opposition, yet he managed to make vetoes a weekly event. This occurred, in part, because the Democratic Congresses did not mind. Many legislators obliged the president’s famous request, “Send me a bill I can veto,” understanding that each rejection could cast the party in a positive light. Legislature or president, the noble defender was always a Democrat. It was masterful stagecraft.

41

No one dismantled the authority of Congress more than FDR, and the veto was among his favorite cutting tools.

The partisan high tide came with the Seventy-Fifth Congress (1937–38), in which Senate Democrats outnumbered Republicans 75 to 17. In the House, the ratio was an astounding 333 to 89. And still Roosevelt’s vetoes came, reminding both Capitol Hill and the nation just who was in charge. As was his style, he worded most vetoes in grand moral themes. A perfect example involved the Senate’s simple request to rename the Chemical Warfare Service to the “Chemical Corps.” Rather than just say no, FDR publicly declared, “I do not want the Government of the United States to do anything to aggrandize or make permanent any special bureau of the Army or the Navy engaged in these studies. I hope the time will come when the Chemical Warfare Service can be entirely abolished.”

42

In FDR’s final years, as his health deteriorated, so did his hold on Congress. A showdown emerged over the Revenue Act of 1943, a hopelessly convoluted measure that favored the wealthy. Roosevelt angrily vetoed it, saying, “It is squarely the fault of Congress of the United States in using language in drafting the law which not even a dictionary or thesaurus can make clear.” He added, “These taxpayers, now engaged in an effort to win the greatest war this Nation has ever faced, are not in the mood to study higher mathematics.”

43

Deeply offended by FDR’s scolding, Senate majority leader Alben Barkley immediately resigned from his post. In response, his associates unanimously reappointed him, and both houses overruled the president’s veto within forty-eight hours.

44

In 1943, FDR vetoed a joint resolution to designate December 7 as “Armed Services Honor Day.” He called the measure “singularly inappropriate” as he believed the anniversary should be remembered as “one of infamy” rather than a national holiday.

2

. GROVER CLEVELAND (584)

REGULAR VETO: 346

POCKET VETO: 238

OVERRIDDEN: 7

In Buffalo, they called him “Veto Mayor.” In Albany, it was “Veto Governor.” Elected to the White House in 1884, partly for his reputation of stemming frivolous legislation, he became “Old Veto.” Whereas FDR later killed one out of every twelve bills, stubborn Grover Cleveland stopped one out of every six. In his first term alone, the New York Nix rejected 414 legislative acts, twice as many as all preceding presidents combined.

45

More than 80 percent of his targets involved personal disability pensions, mostly from Union veterans of the Civil War. While the Pension Bureau handled over half a million of these submissions, many of the rejected cases found new life as private bills in Congress, submitted by legislators looking to gain favor back home.

46

Most pensions were modest and justified. Enlisted men who lost both feet were eligible for a pension of twenty dollars a month. Loss of both hands or both eyes meant five dollars more. Yet several requests were extremely dubious, pricey, and piling up. On a single day in mid-1886, Cleveland received no fewer than 240 pension bills, many of which belonged to, in Cleveland’s words, “bums” and “blood-suckers.”

47