History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (21 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

An outraged South Carolina was first to revolt against the government, mere weeks after the election. The official article of secession proclaimed: “A geographical line has been drawn…and all the States north of that line have united in the election of a man to the high office of President of the United States, whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery.”

65

Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas soon followed, declaring a betrayal of democracy. Seizing federal arsenals, foundries, and forts, forming their own constitution, and electing their own president, the Confederate States of America determined to have their new nation up and running before the “Black Republican” took the oath of office. As one Georgia newspaper affirmed: “Let the consequences be what they may—whether the Potomac is crimsoned in human gore, and Pennsylvania Avenue is paved ten fathoms deep in mangled bodies…the South will never submit to such humiliation and degradation as the inauguration of Abraham Lincoln.”

66

Of the defeated candidates in 1860: Douglas died the following year from typhoid; Breckinridge fought in the Confederate army; and Bell eventually supported secession, while his running mate, Edward Everett, was the keynote speaker at the dedication of the Soldiers Cemetery at Gettysburg just prior to Lincoln’s delivery of the Gettysburg Address.

2

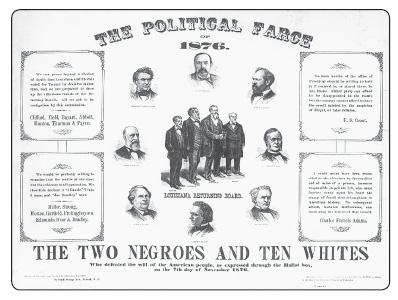

. “THE MONSTER FRAUD OF THE CENTURY”—1876

| RUTHERFORD B. HAYES (R) | 185 |

| SAMUEL J. TILDEN (D) | 184 |

“Reconstruction” was a misnomer. A decade after the largest war ever waged in the Western Hemisphere, Americans were still trapped in the wreckage. Soldiers continued to occupy much of the Deep South, recession and corruption flourished, racial tensions prevailed, and shaky relations between Republicans and Democrats turned absolutely virile.

To maintain their hold on the presidency, many Republicans resorted to “waving the bloody shirt,” reminding voters that the late Confederacy was largely of Democratic construct. They also accused Democratic nominee Samuel Tilden (a highly ethical individual) of racketeering, tax evasion, and anti-Unionism.

In turn, Democrats spread rather interesting rumors about the Republican candidate. Reportedly, Rutherford B. Hayes had pocketed the pay of deceased soldiers under his command during the Civil War, embezzled millions as Ohio’s governor, and killed his mom. The accusations were partially true. Hayes had been an officer in the Union army, served as governor of Ohio, and had a mother.

67

Conditions were far worse in the South. Democratic “rifle clubs” began to harass Republicans, white and black. Vicksburg witnessed a bloodbath right before a local election in 1874—thirty-five blacks and two whites were killed in the wake of a political riot. In 1875, neighboring states began to adopt the “Mississippi Plan,” a combination of blacklisting and physical harassment against “carpetbagger” Northerners and African Americans. In South Carolina, on the hundredth anniversary of the Fourth of July, a confrontation between white gentry and black militia led to the “Hamburg Massacre.” Five of the militia were captured and summarily shot “while trying to escape.”

68

Predictably, the election of 1876 became a spectacle of voter intimidation and falsified counts, to the point where another civil war seemed inevitable. Neither candidate won a majority of the Electoral College (see C

LOSEST

E

LECTIONS

) because Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina submitted multiple, contradicting results. In a show of force, President Grant sent thousands of additional troops to the South. Questionable recounts produced swings of ten thousand votes and more. Squads of factional “Minute-Men” began to arm themselves. Democrats demonstrated across the country shouting “Tilden or Blood,” while their representatives on Capitol Hill presented a resolution naming Tilden as president.

69

One day before the end of Grant’s term, a bipartisan committee placed the Republican Hayes in the White House. Miraculously, war was averted. Though the Democrats lost the presidency, they retained control of the House and subsequently cut off all funding for Reconstruction. Facing a divided Congress and a divided country, Hayes opted to postpone civil rights in return for Southern cooperation, and he ended the military occupation of the former Confederacy.

70

Sour grapes for the Democrats in 1876 were directed against the bipartisan committee that gave the White House to Republican Rutherford B. Hayes.

Refusing to accept Hayes as their president, militant Democrats displayed flags at half-staff and referred to the chief executive as “His Fraudulency” and “Rutherfraud B. Hayes” throughout his four-year term.

3

. REVENGE FOR “THE CORRUPT BARGAIN”—1828

| ANDREW JACKSON (D) | 178 |

| JOHN QUINCY ADAMS (NR) | 83 |

The election of 1824 was civil enough. Finishing last was House Speaker Henry Clay, with Treasury Secretary William Crawford third and Secretary of State John Quincy Adams second. Reflecting the country’s physical and political drift westward, Senator Andrew Jackson of Tennessee won a plurality of the popular vote, but his 99 electors were well short of the 131 required for a majority.

Mandated by law, the decision went to the House of Representatives. Under Clay’s watch, they chose the experienced Adams. At first, Jackson expressed surprise but not suspicion, until Adams gave Clay the prestigious post of secretary of state. Already prone to a volcanic temper, Jackson raged against the “corrupt bargain,” and his fellow westerners began scheming to oust Adams in 1828.

They had an easy target. John Quincy was much like his father, only more haughty, cerebral, and distant. He spoke in ideals, of building a national university and an astronomical observatory, items of marginal appeal to the 90 percent of Americans who lived in the rural world. Pouncing on the pompous intellectual, Jackson partisans spread rumors that “King John II” was turning the Executive Mansion into a palace of intrigue, filling it with “gambling equipment” (in truth, a billiard table). They also alleged that he secretly despised anyone who was not of English blood. Stories surfaced that while Adams was ambassador to St. Petersburg, he coerced a young woman into an affair with Czar Alexander I, a lie that mutated into accounts of Adams “the pimp” gathering prostitutes and virgins for the entire royal court.

71

Revolted by this new political party of frontier mudslingers who took the name “Democrats,” Adams’s National Republicans responded in kind. They derided Jackson as a cruel slave master, uneducated, partial to cockfights, and a murderer (he executed two British captives during the War of 1812). They also attacked his wife. An ailing woman of sixty-one, Rachel Donelson Robards Jackson had once been married to an abusive husband. He eventually left her, though he neglected to finalize their divorce. Assuming otherwise, Rachel married Jackson, who adored her. In 1828, when an unfriendly press caught wind of the ancient (and long rectified) problem, they incessantly accused her of adultery.

The attacks failed to shake Jackson’s appeal to the masses, and he won in a landslide, but he would lose his wife. Two weeks after the election, the emotionally shattered and publicly defiled Rachel suffered a severe heart attack. Doctors bled her, and she recovered slightly, only to succumb to a cardiac arrest. Under orders from her husband, doctors bled her again, this time from the temple. Rachel had been dead for hours before her husband stopped checking for her pulse.

72

The revered Henry Clay of Kentucky was in the middle of the fiery election of 1824. Initially Andrew Jackson had no reason to suspect House Speaker Clay of any wrongdoing when the House made John Quincy Adams president in 1825. That all changed, however, when Adams named Clay as his secretary of state.

Weeks later, Jackson left for Washington. As he entered the city where his rivals were still in office, Jackson declared, “May God Almighty forgive her murderers as I know she forgave them. I never can.” Perhaps wisely, both Clay and Adams did not attend the inauguration.

73

On Christmas Eve 1828, Rachel Jackson was laid to rest wearing the dress she had bought for her husband’s inauguration day.

4

. “MURDER, ROBBERY, RAPE, ADULTERY, AND INCEST”—1800

| THOMAS JEFFERSON (D-R) | 73 |

| JOHN ADAMS (F) | 65 |

The two had once been dear friends, having met at the Second Continental Congress. John Adams marveled at the spindly Virginian’s literary brilliance. Soft-spoken Thomas Jefferson was quickly impressed by the forceful and confident little stove from New England, seven years his elder. Their bond lasted twenty years, until they were president and vice president. Belonging to rival factions, the two abruptly drifted apart and rarely spoke to each other during the whole of their administration.

The bitter election of 1800 only widened the fissure. Awaiting the outcome back home in Massachusetts, Adams confided, “I am determined to be a Silent Spectator of the Silly and Wicked game.” Jefferson busied himself with endless modifications to Monticello. The factions fought anyway.

74

The pivotal question involved which superpower to embrace: Britain or its mortal enemy France. The Federalist Adams favored the former, and his enemies consequently branded him a royalist. James Madison cursed the Federalists as “the British Party,” while others claimed that a reelected Adams would rejoin the monarchy and make himself royal governor of North America.

75

Jefferson won several enemies for his well-known favoritism of France, a place that had turned to mob rule in the 1790s. As Europe sank once again into fratricide, Jefferson’s enemies recounted a statement he had made years before: “I like a little rebellion now and then.”

76

Then there was the question of Jefferson’s own faith, summarized in his famous statement, “for my neighbor to say that there are twenty gods, or no god…It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.” His foes construed this as a profession of atheism, and Alexander Hamilton branded him “an Atheist in Religion and a Fanatic in politics.” Another Federalist proclaimed that a Jefferson victory would mean “religion will be destroyed and immorality will flourish,” while the

Connecticut Courant

declared: “Murder, robbery, rape, adultery, and incest will be openly taught and practiced.”

77

Fears only worsened when Jefferson and his running mate, Aaron Burr, tied in the electoral vote, and the Federalist-controlled Congress refused to name either one as president (see C

LOSEST

E

LECTIONS

). Citizens openly wondered if the Federalists were planning a coup. Rumors spread in January 1801 that a civil war was imminent after a mysterious fire broke out in the Treasury Department. Jefferson himself warned Adams that there would be “resistance by force, and incalculable consequences” if Congress did not choose a successor—and soon.

78