History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (9 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

In office he began every day with a short service, where his father-in-law, the Reverend John Scott, led the family in prayer. A self-described born-again, Harrison alienated prominent Republicans by selecting a rather anonymous and unaccomplished cabinet; vital to Harrison’s criteria, nearly all of them were declared Presbyterians.

66

Like his grandfather, he was a Sabbatarian, refusing to conduct any official business on Sundays. The national media couldn’t help notice that while the moralizing Harrison cherished the day by not working, he would occasionally play pool or go on extended treks in the countryside.

67

Ultimately, the popular Harrison lost favor. Certainly intelligent, industrious, and committed to conducting the basic necessities of his job, he failed to win the hearts and minds of his fellow Americans in part because his paradoxical behavior looked so much like hypocrisy.

Benjamin Harrison’s promotional campaign biography was written by Lew Wallace, author of the religious epic

Ben Hur.

8

. GEORGE H. W. BUSH (EPISCOPALIAN)

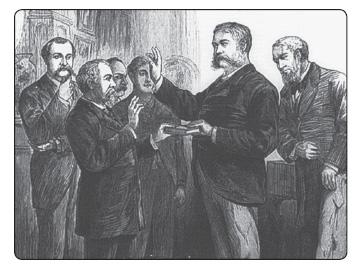

Tenacious is the legend that George Washington added the words “so help me God” when he first took the oath of office. Actually there is no firsthand evidence of an executive uttering the addition until Chester A. Arthur in 1881. Arthur’s invocation, said at a time when only 20 percent of Americans regularly attended church services, did not become an inaugural tradition until the late 1930s, when 50 percent of Americans were routinely going to the pews.

68

By 1989, the “oath after the oath” was customary, and George H. W. Bush took the piety one step further in his inaugural address. “And my first act as President,” he announced to the world audience, “is a prayer. I ask you to bow your heads…”

Fundamentalists were initially cold to his puritanical northeastern roots and his relative restraint compared with the prophesizing Reagan. Not surprisingly, Bush finished third in the Iowa caucuses behind Kansas senator Bob Dole and televangelist Pat Robertson. But as the campaign progressed, he pushed good-versus-evil rhetoric, championed prayer in public schools, and mentioned God in nearly every campaign speech. On November 8, 1988, the Episcopalian scored an astounding 88 percent of the evangelical vote.

69

As president he continued to pray daily and attend services weekly, yet Bush viewed his faith much like he viewed his politics: “I’m a conservative, but I’m not a nut about it.” His prayer-in-school statements never manifested into action, nor did his attempt to order the Pledge of Allegiance in schools. To the Supreme Court he appointed David Souter and Clarence Thomas, both of whom were right of center but not to any extreme, and neither were adamantly opposed to the religious Right’s nemesis,

Roe v. Wade

.

Not until Chester A. Arthur was there a verified instance of a president concluding his oath of office with the phrase “so help me God.”

Only when it was time for reelection did Bush replay the God card, and the message had lost its edge. In the polls, nearly every denomination reduced its support. The largest hit came from evangelicals—nearly 40 percent eventually voted against him.

70

George H. W. Bush and eight other presidents were Episcopalians. Eight more were Presbyterians. Together the two denominations represent more than 40 percent of the past chief executives but less than 5 percent of the American population.

9

. RICHARD NIXON (QUAKER)

When Hubert Humphrey conceded the 1968 election, Nixon summoned a longtime spiritual confidant to his suite at the Waldorf Towers in Manhattan. When the guest of honor arrived, the president-elect, daughters Tricia and Julie, and wife Pat joined hands with Billy Graham, formed a circle, and praised “God’s plan for the country.”

71

In his first weeks in office, Nixon started nondenominational services in the White House. According to Nixon, it was intended to keep his devotion private. His aide John Ehrlichman considered it a political display. The Sunday gathering in the East Room soon became a prestigious event, attended by the elites of religion and Washington alike, with church choirs, organists, and Billy Graham as common fixtures.

72

Such was the enigmatic Nixon, private yet public in worship, strait-laced yet profane, utterly faithful to a wife he rarely acknowledged. Somewhat forgiving of his joining the navy in the Second World War, fellow Quakers heavily opposed his militarism in Indochina. At the same time, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Thomas Moorer, was somewhat beleaguered when Nixon insisted that no bombing raids on Vietnam should occur on a Sunday, whether the Sabbath was hovering over East Asia or North America.

73

Nixon was not an evangelist. A Quaker in name all his life, he sporadically praised many faiths, from the unassuming honesty of his mother’s Society of Friends, to the grand ritual of Catholicism, to the political prestige of Presbyterians. During the darkest hours of W

ATERGATE

, he sought a rabbi for spiritual guidance. Much like his relationship with the Constitution, he explored the depths of religion but was uncomfortable with its strict guidelines.

74

Perhaps nothing summarized his religious convictions or his innate complexity more than a statement he made to his trusted

CHIEF OF STAFF

, Bob Haldeman. Sequestered at Camp David in the last days of his presidency, Nixon confessed: “You know, Bob, there is something I’ve never told anyone before, not even you. Every night since I’ve been president…I’ve knelt down on my knees beside my bed and prayed to God for guidance and help in this job. Last night before I went to bed I knelt down, and this time I prayed I wouldn’t wake up in the morning.”

75

Thus far, two Quakers have become president: Richard Nixon and Herbert Hoover, which is two more than Lutheranism, the largest mainline Protestant denomination in the United States.

10

. JOHN QUINCY ADAMS (UNITARIAN)

Of the early presidents, John Quincy Adams was the most public in his expressions of faith, and he was also the most cerebral. It was therefore no accident that he wrestled with matters of theology, for he treated faith as a wondrous enigma to be openly discussed as with any mystery of the universe.

While president he scoured the Bible often, and on Sundays he attended services twice: Unitarian in the morning and Presbyterian later in the afternoon. Religion for him was investigation, and while Adams embraced the concept of a divine being, he questioned the probability of a divine human on earth or the possibility of a virgin birth. Miracles, parables, and practices were all intriguing avenues for contemplation. He felt welcome in almost any religious environ, though the long and quiet services of Quakers bored him immensely. Later in life, he found radical departures such as Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Transcendentalism to be too ethereal, even for him.

Adams did not join a church until he was president. It was to be Unitarian Congregationalism, the church of his less reverent father. The two men would come to share many traits in faith—admiration for a human Jesus, skepticism toward a Holy Trinity, and dismissal of predestination. Yet while the senior Adams was content to be a good person, his son possessed an innate restlessness, a desire to search eternally for an absolute truth, one that could only be achieved through resolute and open pontification.

John Quincy Adams and his father are among the very few presidents who are buried in a religious setting. The Adamses and their brides are interred beneath the Congregational Church in Quincy, Massachusetts.

If the institution has mutated from a subdued patronage into an imperial presidency, then it would stand to reason that the presidents have gone from being fatherly figures to resembling

The Prince

, Niccolo Machiavelli’s archetype of the power-hungry politician. In actuality, there have been autocratic presidents from the Republic’s beginning, and these Machiavellian types have been among the most revered.

While it is true that recent candidates have been far more aggressive than their forbearers in running for the office, they generally have not ruled with a firmer hand once they were in power. If anything, modern presidents have become hypersensitive to the wants and needs of the country as a whole. More than ever, their job security depends on their ability to appeal to the masses. George Washington presided over a population of four million, but his electorate was 4 percent of that—a small portion of the white, male property owners in the country. Seventy percent of Barack Obama’s America had the right to vote in 2012, including every race, ethnicity, religion, literacy level, and income bracket imaginable, male and female, age eighteen and above.

76