History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (8 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

Americans liked their candidates to be upstanding, but preachy types were still considered suspect in the late nineteenth century. One of the reasons McKinley won the election of 1896 was that he was the

lesser

of two evangelicals. Nebraska Democrat William Jennings Bryan (later Woodrow Wilson’s secretary of state and the prosecuting attorney in the 1925 Scopes trial) was so forthright in his Presbyterianism that he effectively alienated the largest religious minority in the country—Roman Catholics.

The comparative moderate, McKinley was still the most openly religious president the country had yet elected. His inaugural address nearly sounded like an excerpt from the Old Testament. “Our faith teaches that there is no safer reliance than upon the God of our fathers,” moralized McKinley, “who will not forsake us so long as we obey His commandments and walk humbly in His footsteps.”

Yet he was sincerely penitent. Warmhearted, humble, tender, and faithful to his afflicted wife (Ida suffered from random, crippling seizures), McKinley was the model believer. While in the White House, he attended Metropolitan Methodist Church, prayed daily, and often invited guests to sing hymns in the Blue Room.

49

McKinley was no imperialist, but he did support the growing network of Christian missionaries across the globe. Attending an ecumenical missionary conference in Carnegie Hall, the president blessed their work with a convocation: “May this great meeting rekindle the spirit of missionary ardor and enthusiasm [for] the continuous proclamation of His gospel to the end of time.”

50

Much of that missionary zeal had spread to the Philippines, which the U.S. armed forces had recently pried from the clutches of Imperial Spain. Compelled to explain why he decided to conquer and occupy the country and promote Protestant missions therein, McKinley explained to a group of fellow Methodists, “I went down on my knees and prayed Almighty God for light and guidance.” He then told his audience of the epiphany, “There was nothing left to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them, and by God’s grace do the very best we can by them, as our fellowmen for whom Christ also died.”

51

McKinley’s well-intended exploits received a great deal of criticism, especially from those who feared America was simply replacing Spain as the new ruler of the archipelago. Indeed, it would be another war and another forty-five years before the United States granted Filipinos their independence, but McKinley would not live to see it. His assassination in 1901 spared him of any further criticism for his reluctant crusade and made him a martyr to nationalists and missionaries alike.

Before he finally succumbed to his mortal wounding, William McKinley’s last words were: “It’s God’s way. His will, not ours, be done. Nearer my God to Thee.”

5

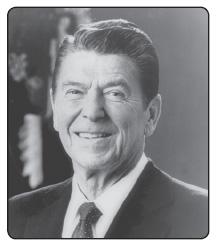

. RONALD REAGAN (PRESBYTERIAN)

In 1980, Reagan became president by being the anti-Carter. Patriotism over penitence, the swift sword over the olive branch, the self-assured over the self-denied. Whereas the peanut farmer portrayed himself as unique, Reagan made himself out as the All-American, possessing something in common with all fellow members of “God’s Country,” and in no venue did he better achieve this than in the rough waters of religion.

Doctrine was not a major part of Ronald Reagan’s early life, nor would it ever be. He often mentioned how his father was a Catholic and his mother a Protestant, but aside from a sense of tolerance for the God-fearing, they imbued in him no strict code or scriptural familiarity. He dabbled in the Disciples of Christ and Presbyterianism but preferred the ambiguity of revival transformation—to feel saved is to be saved. And in his mature years, he swaddled the cross in the flag, espousing a belief he called “faithful patriotism.”

52

Fundamentalists who had backed Carter four years earlier widely supported his questioning of evolution, his advocacy of school prayer, and his opposition to abortion. His staff and cabinet included hardline evangelicals, such as special assistant Morton Blackwell and Education Secretary Robert Billings. Cold Warriors cherished his zeal against the agnostic Soviet system, which Reagan described to an Orlando church group as “a sin and evil in the world, and we are enjoined by Scripture and the Lord Jesus to oppose it with all our might.” In his annual addresses to Congress, Reagan broke with tradition and repeatedly used the word

God

. It was with sincerity that Jerry Falwell, president of Moral Majority Inc., considered Reagan’s victory in 1980 “my finest hour.”

53

However stirring he may have been, Reagan often ran into trouble with clerics. Many groups, including the National Council of Churches, openly rejected his reduction of social services, his favoritism toward the wealthy, and his tendency to support right-wing dictatorships in third-world countries. In 1983, Reagan claimed the papacy supported his pro-Contra operations in Nicaragua. It did not, and the Vatican publicly corrected him.

54

Nor were historians fond of his rewriting the spiritual past. He often depicted Puritans as champions of religious freedom, the same Puritans that openly persecuted Jews, Catholics, and Quakers. The president also painted Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson as devout believers, while they were actually among the most skeptical of the Founding Fathers. In recounting the Philadelphia Convention of 1787, Reagan liked to state that the framers “opened all the constitutional meetings with prayer.” In fact, the framers almost unanimously rejected such a proposal.

55

But the general public welcomed Reagan’s message of American righteousness. In the 1984 elections, he won more than 65 percent of the Methodists, 66 percent of Lutherans, 68 percent of Presbyterians, and 81 percent of white evangelicals.

56

Ronald Reagan was the first divorcee ever elected president.

6

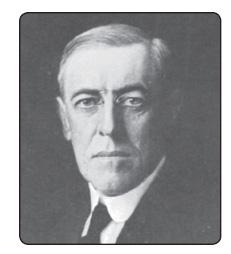

. WOODROW WILSON (PRESBYTERIAN)

Both Theodore Roosevelt and his rival Woodrow Wilson thought in moral absolutes. Yet TR’s ethics were based primarily on a personal sense of right and wrong, while Wilson believed that all things were preordained by God, including his presidential election in 1912.

57

Wilson’s father, grandfather, and uncle were all Presbyterian ministers. In his youth, Woodrow felt no great desire to follow in their footsteps until his college years. One night, the eighteen-year-old scribbled in his journal about a life he viewed as misspent. “I have increased very little in grace,” wrote the troubled man, “and have done almost nothing for the Savior’s Cause here below.”

58

Initially conservative, Wilson gradually adopted the sentiments of his predominantly progressive family, who viewed social reform rather than prayer as the clearest path to salvation. As an adult, Wilson summarized his new worldview in a speech before a YMCA assembly, insisting, “If you will think about what you ought to do for other people, your character will take care of itself…And that is the lesson of Christianity.”

59

He never wavered in his rhetoric. To a White House visitor in 1915, he said, “My life would not be worth living if it were not for the driving power of religion, for faith, pure and simple.” While president he served as an elder in Washington’s Central Presbyterian Church, went to prayer meetings every Wednesday, and read the Bible nightly. To him, Christianity was “the most vitalizing thing in the world.”

60

Nowhere were his convictions more apparent and annoying to others than in his diplomatic mission to Versailles, where the savior-American proceeded to preach upon the warring Continentals. Taken aback by Wilson’s hubris, French president Georges Clemenceau said, “He thinks he is another Jesus Christ come upon the earth to reform men.” Equally surprised was British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, who thought Wilson was acting like “a missionary” who had come “to rescue the poor European heathen.” Directing European relief programs at the time, philanthropist Herbert Hoover knew Wilson could not turn it off, calling the president “a born Crusader.”

61

Wilson’s rigor at Versailles was heartfelt but ineffective. Europe pulled the teeth from his progressive Fourteen Points, and the U.S. Senate refused to ordain his League of Nations. But he did score a major victory in terms of his faith. He lent his support to Britain’s Balfour Declaration, a secret policy statement backing the formation of a Jewish state in the old Ottoman Empire. Shortly before his death, he believed Israel was about to become a political reality, and he viewed its creation in purely religious terms. “To think that I, a son of the manse,” he said in confidence to an associate, “should be able to help restore the Holy Land to its people.”

62

To demonstrate “due regard for the Divine Will,” Woodrow Wilson ordered U.S. forces in the First World War to work and fight as little as possible on Sundays.

7

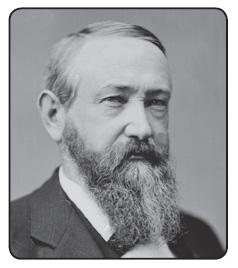

. BENJAMIN HARRISON (PRESBYTERIAN)

“He is a cold-blooded, narrow-minded, prejudiced, obstinate, timid old psalm-singing Indianapolis politician.” Theodore Roosevelt may have been a tad callous in his assessment of Benjamin Harrison, but he was not alone in the sentiment. Harrison was hard to like, in part because he was such a contradiction. He could charm crowds with his brilliant oratory, but in person he was tactless and aloof. He would skip out of the White House to play with his grandchildren, yet squeeze twelve-hour workdays out of his staff. Apt to change his mind often, he chastised anyone who dared contradict him.

63

Harrison was born in 1833 in the hinterlands of Ohio, a time and place deep in the evangelical throws of the Second Great Awakening. His parents were devout, as was his presidential grandfather. By age twenty-seven he was an elder in the church, a Sunday-school teacher, and a deacon. He intended on going into the ministry until he surmised that an eager Christian could do more in politics. As he once told his fellow students at Miami of Ohio, “Civil society is no less an institution of God than the Church.”

64

The chance to become the nation’s premier civil servant came in the election of 1888. He won primarily due to the relentless efforts of a well-organized and well-funded Republican hierarchy. Harrison, however, chalked his win to something else. Hearing he had won, Harrison vigorously shook the hand of national Republican chairman Stan Quay and beamed, “Providence has given us victory.” Angered by the candidate’s lack of gratitude, Quay later said, “He ought to know that Providence hadn’t a damn thing to do with it.”

65