History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (11 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

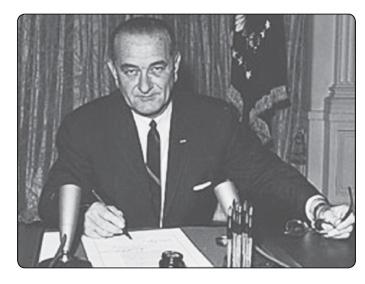

A pensive Lyndon Johnson signs the Gulf of Tonkin resolution. For the next nine years, the executive branch assumed legislative authority over war making.

With blank check in hand, LBJ did something even more remarkable, something almost dictatorial in its absoluteness. He did nothing. Month after month, he rejected plans from the Department of Defense to carpet bomb North Vietnam. He also refused any substantial buildup beyond the seventeen thousand troops already present in South Vietnam. Not until his power was secured through his election in November, and his Great Society was set in motion, did he decide to address the seemingly minor issue of Southeast Asia. Fortunately for Johnson, his options were wide open, thanks to the infinite latitude he quickly and easily wrested from Congress in the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution.

A title befitting his character, LBJ’s nickname in college was “Bull.”

5

. WOODROW WILSON

THE SEDITION ACT (1918)

On the surface, Wilson was an accomplished and revered academic, a rousing public speaker, and worldly. In private, he was a rather crass and lonely figure. He struggled with intimacy on all levels, he demanded absolute loyalty from an ever-shrinking circle of friends, and he found humor in mimicking other ethnicities.

88

His speeches made him sound like an idealist, as demonstrated in his first inaugural address in 1913. “The feelings with which we face this new age of right and opportunity sweep across our heartstrings like some air out of God’s own presence,” he assured with his scholarly, melodic tone, “where justice and mercy are reconciled and the judge and the brother are one.” Taken in context, he was no more optimistic than most educated progressives at the time, trained in the flowery language of the Gilded Age and facing a new century of unparalleled promise.

But he could be medieval when it counted. His late and reluctant entry into the World War unearthed his basic instincts of survival, and while he planned to fight for democracy in Europe, he suspended it indefinitely at home. Under his heavy pressure and precise direction, Congress passed the Trading with the Enemy Act (still in effect today), the Espionage Act (ten-thousand-dollar fine and twenty years in jail for doing or saying anything against the military draft), and the Alien Act (immediate deportation of any suspected anarchist).

As wartime patriotism surged, Wilson forged ahead with the most virulent edict of his administration: the Sedition Act of 1918. The law made it illegal for anyone to “utter, print, or publish disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government, the Constitution, soldiers and sailors, flag, or uniform of the armed forces.” Several citizens pointed out that the law itself was abusive toward the Constitution, and they were summarily arrested.

89

Woodrow Wilson actively persecuted freedom of speech and press under the wartime Sedition Act.

Through the Sedition Act alone, more than fifteen hundred Americans were taken into custody under the guise of national security, and more than one hundred of them were convicted and imprisoned. One of the more ludicrous cases involved a member of the clergy from Vermont who suggested that Jesus of Nazareth was a pacifist. For spreading such a treasonous rumor, the pastor was sentenced to fifteen years behind bars.

90

Woodrow Wilson’s draconian laws during the Great War inspired the creation of the American Civil Liberties Union in 1920.

6

. RICHARD NIXON

“THE PLUMBERS” (1971–73)

His first four years confirmed he would do whatever it took to reach desired ends: freeze government wages, desegregate schools, abandon the gold standard, bomb rice patties, and visit Communist China. For his cold, calculating, slightly vengeful work, the nation rewarded the conservative and secretive leader with a four-year extension to his contract.

What the electorate did not know—yet—was that he was able to run a tight and efficient White House because he had hired his own palace guard. In the wake of the embarrassing P

ENTAGON

P

APERS

incident, Nixon instructed domestic policy adviser John Ehrlichman to form a “Special Investigations Unit.” After some hunting, Ehrlichman created a group that would be known as “the Plumbers,” so-called because their job was to stop all internal leaks. The central figures were David Young, a former assistant to Henry Kissinger, and Bud Krogh, a lawyer and close family friend of Ehrlichman. The team expanded to include former FBI agent G. Gordon Liddy and former CIA employee (and Bay of Pigs operative) E. Howard Hunt.

91

Rather than prevent information from seeping out, the group began to bring large amounts of intelligence in. Colluding with others, including the dubious Committee to Reelect the President (a.k.a., CREEP), the Plumbers engaged in wiretapping, examining tax returns of political opponents, pilfering CIA records, and scheming to illegally photograph classified information in the National Archives. The cell even created an enemies list to better target the suspected opposition, which included individuals in Congress and the private sector. Most of these activities were unknown to the president, yet he was generally aware that much of what they were doing was not legal.

92

To what extent any of their covert activities helped Nixon remain in power is difficult to determine. Still popular among moderates and conservatives at the end of his first term, the incumbent Nixon probably would have won reelection by a wide margin regardless of the Plumbers. But their existence reflected the extent of hubris that had permeated the secretive Nixon White House, and their botched breakin of the Democratic national headquarters at the W

ATERGATE

led to the destruction of the very institution they were breaking the law to protect.

Founder of the Plumbers, John Ehrlichman, and Nixon’s chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman, were both Eagle Scouts.

7

. GEORGE W. BUSH

THE WMD PRESENTATION TO THE UN SECURITY COUNCIL (2003)

Closer to his mother than his father, who was often away on business, George W. Bush assumed the role of family protector at an early age. In many respects, he acted like a morale officer rather than a leader, a persona he maintained throughout his life. At Phillips Academy and Yale, he enjoyed the social aspects of school, including cheerleading, but he developed a deep suspicion of intellectuals. Though inherently friendly and outgoing, he was not terribly open or conscientious. Like his father, he learned to fly fighter planes and entered the oil business. Unlike his father, he trusted his emotions more than his intellect.

93

As an adult, G. W. Bush displayed a curious tendency to smile in awkward situations. The habit became most prominent during his presidency, especially when responding to questions about war, terrorism, or natural disasters. Largely involuntary, the trait is a defensive response to the stimulus of pain or discomfort. His father did not have this inclination, but Richard Nixon and Lyndon Johnson did, both of whom frequently smiled broadly after talking about emotionally difficult subjects. A wince more than a grin, it is a telltale sign that a person is not being straightforward.

94

Bush and his administration never actually tried to emphasize honesty as their overriding quality. Instead, the operative words were “leadership,” “strength,” and “commitment.” Bush was also personally fond of the word

freedom

, using the word twenty-seven times in his second inaugural. It was under the premise of making the world “free from terror” that he initiated a preemptive strike on Iraq in 2003.

Evidence to justify such an operation was not available, so the Bush administration did the next best thing: they guessed. Vice President Dick Cheney and the assistant secretary of defense, Paul Wolfowitz, engineered a sales pitch based on allegations that Iraq was manufacturing weapons of mass destruction and was directly connected to terrorist organizations. To deliver this war message, they chose the most trusted member of the administration, Secretary of State Colin Powell. Hopefully the ensuing Second Gulf War would go as well as the First, and if it did, the ends would justify the means.

In hindsight, they were trying to pull an Adlai Stevenson. At the height of the C

UBAN

M

ISSILE

C

RISIS

, Kennedy’s UN ambassador presented photographic proof to the Security Council that the Soviet Union was assembling tactical and medium-range nuclear missiles in Cuba. The overwhelming evidence and clear images brought virtually all of South America and Western Europe on the side of the United States.

At the height of the War on Terror, on February 5, 2003, Bush’s secretary of state entered the Security Council and provided “irrefutable and undeniable” evidence that Iraq was assembling weapons of mass destruction in secret locations. With surveillance technology forty years ahead of what Stevenson had, all that Powell showed were blurry images of “weapons factories” that looked more like shopping malls from ten thousand feet. The computer-generated drawings of the mobile “biological agent” trucks were even less impressive. Unconvinced, the nations that had sided with the Kennedy administration in 1962 were reluctant to believe George W. Bush in 2003. Undeterred by the cold reception, the Bush invasion proceeded as planned. Though unsuccessful in finding any WMDs or proof of terrorist connections, the war did install a pro-West president in Baghdad and allowed George W. Bush to retain his job for a second term.

95

In a television interview in 2005, a retired Colin Powell described his erroneous presentation at the UN Security Council as “painful.”

8

. GEORGE WASHINGTON

REPRESSION OF THE WHISKEY REBELLION (1794)

The stalwart and physically imposing Virginian rarely spoke, stood rigidly upright, and moved with a regal stride, bringing some to the false conclusion that he was pompous. Among the least educated of the Founding Fathers, George Washington took a great deal of time to reach a conclusion, but once the decision was made, he moved with the steady force of a river current. Though utterly trustworthy, he had a difficult time trusting others, and he let very few get close to him. He did not take criticism well.

“I walk on untrodden ground,” Washington acknowledged. “There is scarcely an action the motive of which may not be subjected to double interpretation.” His service was an exercise in restraint, and when dealing with untested issues, he preferred to err on the side of caution. There was one facet of the new government that needled him: the provision in the 1791 Bill of Rights that guaranteed freedom of the press. Galled by the liberal wing of the media who openly suspected him of wanting to become king, Washington said in 1792: “In a word if the Government and the Officers of it are to be the constant theme for Newspaper abuse, and this too without condescending to investigate the motives or the facts, it will be impossible, I conceive, for any man living to manage the helm, or to keep the machine together.”

96

Obliged by law to tolerate dissent in the form of print, Washington denounced any threat of violence against the government. A neutral in foreign wars, he did not hesitate to play commander in chief on his own people. And when farmers and merchants began to gather arms against a law they thought immoral, the president amassed an army larger than anything he brought to bear against the British and sent it to crush the resistance.