History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (46 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

Fortunately, the framers knew to temper dictatorial lust by granting Congress sole responsibility to declare and finance wars. Adding to the checks and balances were a judiciary to monitor the use of war powers and an electorate capable of deposing militant executives through regularly scheduled elections.

In general, the collective effort has created a rather impressive war record, but presidents sometimes falter anyway, especially when it comes to their prewar objectives. During the course of conflicts, such goals are frequently compromised or abandoned altogether. The most glaring failures have involved the promises of short fights and modest loss of life—popular selling points that have proven difficult to deliver. While no leader has seen a military engagement go completely as planned (armed opponents rarely cooperate), some have faltered terribly through mismanagement and miscalculation.

Following are the least successful presidents based on the scope of their failed war aims, the duration of their wars, and the damages rendered in blood and money. Interestingly, eight of the following individuals served as officers in the armed forces before they became commander in chief, challenging the popular assumption that candidates with military experience are inherently better suited to lead the country in times of international unrest.

1

. LYNDON B. JOHNSON

VIETNAM (1964–69)

Two years in, Lyndon Johnson realized he had no viable solution. In a private conversation with Lady Bird in March 1965, he painted himself as a victim of circumstance: “I can’t get out. I can’t finish it with what I have got. So what the hell can I do?”

95

For starters, he could have realized he was responsible for causing rampant inflation. A master of domestic politics, LBJ knew very little about world history or international affairs, which led him to critically ignorant assessments of a perennial civil war in a third-world country that was of almost no geographic, economic, or material significance to U.S. national security. In the 1964 presidential election, the electorate correctly perceived the insurgency in Southeast Asia as a minor issue.

96

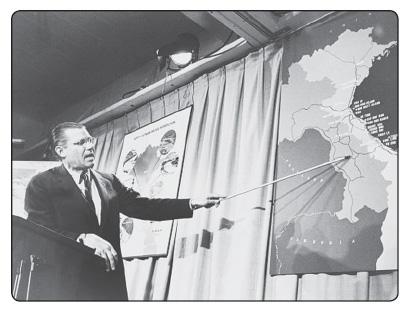

LBJ’s secretary of defense, Robert McNamara, points to the sinkhole of Southeast Asia, where the United States was losing an average of thirty men a day in 1968.

Johnson was not the first to try to subdue the region, to force it into a form of rule to which it was not suited. Before LBJ, there were Kennedy, Eisenhower, Truman, the French Fourth Republic, Imperial Japan, the French Third Republic, and the Chinese. Johnson inherited fifteen thousand U.S. troops in Indochina. But the decision was ultimately his alone to balloon that number to more than a half-million troops and to transform an intraregional conflict into the supreme test of American will.

His impression of the region revealed an embarrassing lack of perspective, one that made him highly susceptible to the doomsday premonitions of N

ATIONAL

S

ECURITY

A

DVISER

McGeorge Bundy and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara (both holdovers from the JFK administration). “If I got out of Vietnam and let Ho Chi Minh run through the streets of Saigon,” Johnson once claimed, “then I’d be doing exactly what Chamberlain did in World War II.” He also believed the “loss of China” to be “chickensh-t compared with what might happen if we lost Vietnam.”

97

To equate the international leverage of Nazi Germany or Communist China with provincial Vietnam takes a great deal of vivid imagination and false information, both of which LBJ had in abundance. His first critical mistake was to inflate a pair of small naval encounters in the G

ULF OF

T

ONKIN

in August 1964 into the worst possible offense to the dignity and safety of the United States imaginable. Poor marks go to Congress for consequently passing a resolution that surrendered most of its responsibilities in military management. But the legislators had incentive. At the time, Johnson had a public approval rating of 70 percent.

By the start of 1965, more than four hundred U.S. advisers and servicemen had died in Vietnam. In an attempt to prevent further loss, LBJ sent in the first of many combat battalions. He also unleashed Operation Rolling Thunder, a massive bombing campaign designed to bring the North Vietnamese to their knees. Reconnaissance and analysis soon revealed that the air strikes were having minimal effect on the largely rural and agricultural country. The president countered that all the strategy would work if the quantity and quality of the bombings were increased. He was soon going so far as to tell the air force what bridges to hit and escalating his troop levels. By the end of the year, eighty-two thousand American soldiers and marines were on the ground, U.S. deaths had climbed to twenty-two hundred, and Rolling Thunder would continue for the next two years.

98

By the time Johnson left the presidency in early 1969, troop levels had surpassed five hundred thousand, fatalities were nearing forty thousand, and the Saigon government was under the control of a virtual dictator in Nguyen Van Thieu, a former military officer who ruled largely through political repression and U.S. aid.

The traditional view is that LBJ’s biggest failure was his lack of a precise strategy for victory. The assessment is largely correct. Americans in 1776 and 1941 proved their country was capable of paying any price, bearing any burden, and meeting any hardship, so long as they had a well-defined goal. But as those two wars also demonstrated, any superpower can be beaten if subjected to the lethal weapons of time and attrition.

99

Technically, Johnson did not lose the war. He would simply pass it on to his successor, just as he had received it from the president before him. But his decision to invest so much in a fight that offered so little in return cost him the White House and destroyed his dream of the “Great Society.” His mistake also eventually ended the lives of fifty-nine thousand young Americans and nine hundred thousand Vietnamese.

In the five years Lyndon Johnson was in office, South Vietnam experienced seven different regime changes, mostly by way of coups.

2

. RICHARD NIXON

VIETNAM, CAMBODIA, AND LAOS (1969–73)

October 1969, Camp David, Maryland—President Richard Nixon wrote a memo to Henry Kissinger. Scribbled on the paper, among other items for Kissinger’s consideration, was a short, solitary question: “Is it possible we were wrong from the start on Vietnam?” The problem for Nixon and his

NATIONAL SECURITY ADVISER

was not their support for the war in the past. It was their plan for going forward. Kissinger joked: “We will not make the same old mistakes. We will make our own.”

100

The Nixon plan had always been to establish a pro-West government in South Vietnam, regardless of its legitimacy or virtue, so long as it was not communist. To achieve this, Nixon initially maintained the Johnson strategy—saturation bombing, shifting the burden of ground security to the Saigon government (what Defense Secretary Melvin Baird dubbed “Vietnamization”), and waiting for the North Vietnamese to cave.

By November 1969, he had been in office nearly a year, and to his surprise, the old methods were not working. In his famous “Silent Majority” speech, Nixon urged his two hundred million fellow Americans to stay the course: “This first defeat in our Nation’s history would result in a collapse of confidence in American leadership, not only in Asia but throughout the world.” A compelling notion, if leadership simply involved winning wars.

101

By 1969, even the bright, optimistic face of Nixon could not raise American morale in Vietnam.

Nixon Library

To give the weak South Vietnamese government time to become self-sustaining, Nixon expanded the war into Cambodia, through which the North Vietnamese were infiltrating the South. In May 1970, he invaded Cambodia with 70,000 men to flush out suspected communist cells. He also accelerated troop withdrawals from Vietnam to appease the antiwar movement in the States. From a peak of 550,000 U.S. servicemen and women in 1969, he reduced the total to 334,600 by the end of 1970.

None of it worked. Campus protests at Kent State in May left four students dead. Civilian and military casualties climbed in Southeast Asia. The bloodthirsty Khmer Rouge attained power in Cambodia. Secret negotiations with North Vietnam produced nothing. Nixon responded by bombing suspected hostile bases in neutral Laos and hinted that he would be willing to use nuclear weapons on Hanoi to achieve peace.

By 1972, troop levels were below one hundred thousand, but the bombings continued. The tonnage dropped on Laos alone was nearing the amount the United States had used in all of World War II. When Hanoi refused to negotiate any further, Nixon launched the infamous Christmas bombings in December 1972—twelve days of air strikes totaling twenty thousand tons of ordnance (or five times what the Allies used in the firebombing of Dresden in 1944).

102

In January 1973, the long-promised armistice was finally achieved. The Nixon phase of the conflict, often seen as a final act in a long tragedy, lasted as long as the American Civil War, and it culminated in defeat.

U.S. aircraft dropped approximately eight million tons of bombs on Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, making them respectively the first-, second-, and third-most bombed nations in the history of aerial warfare.

3

. HARRY TRUMAN (SECOND TERM)

KOREA (1950–53)

Shortly before Christmas in 1950, Harry Truman confided in his diary, “Formosa, Communist China, Chiang Kai-shek, Japan, Germany, France, India,

etc.

I’ve worked for peace for five years and six months and it looks like World War III is here.” His fear of communism was genuine, bolstered by the 1948 blockade of West Berlin, the detonation of a Soviet atomic device in 1949, and the “fall of China” later that year. The anguish only worsened when the leftist dictatorship of Pyongyang invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950. Spearheading their attack of 135,000 men were 120 Soviet-made T-34 tanks, the very machine that broke the Wehrmacht on the eastern front only a few years before.

103

Truman’s counterinvasion of North Korea backfired dangerously, to the point where a frustrated commanding general Douglas MacArthur (right front) advocated the use of nuclear weapons and an all-out war with China. In April 1951, Truman fired the seditious MacArthur, but the quagmire of Korea was still firmly in place.

To stop the offensive, Truman deployed U.S. forces under an emergency UN resolution (but without congressional authority). The rush to defend the Republic of Korea began badly. In a week, Seoul had fallen. Two months later, the late-arriving UN force and the Republic of Korea army held only the toe of the peninsula, an area less than 5 percent of the entire land mass of the two Koreas. The United States was about to experience its first defeat.