History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (44 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

At the time, it was common practice for U.S. presidents to send the navy into troubled waters in an attempt to induce calm. McKinley’s predecessor, Grover Cleveland, had warships pay a visit to Brazil, China, Korea, Nicaragua, and Samoa during periods of unrest. The otherwise isolationist McKinley followed suit and ordered the USS

Maine

into Havana Harbor.

After being anchored in port only a few weeks, the battleship exploded under mysterious circumstances. The detonation killed 266 crewmen on board. Eight more soon died of their wounds, and the public was screaming for revenge.

A distraught president, gentle and even-tempered by nature, offered alternatives to further bloodshed—an armistice on the island, humanitarian aid, arbitration, even the outright purchase of Cuba. Hungry for more decisive punishment, Congress declared war on Spain without McKinley’s request.

75

Fortunately for the placid man from Ohio, his navy was brand-new; the three-year-old

Maine

was the “oldest” of six battleships in the fleet. The navy was also well supplied (thanks to Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt). Facing an unmotivated and outdated opponent in Spain, U.S. warships decimated ten archaic vessels at Manila Bay in the Philippines and patiently awaited the arrival of ground troops from the states. In Cuba, an army of seventeen thousand (including recent volunteer Theodore Roosevelt) ran roughshod over a paltry imperial defense, while the USS

Texas

and company sank the remnants of Spain’s once-glorious armada. After barely seven months of fighting, Madrid was asking for an armistice.

Pious and hesitant William McKinley had an easier time defeating the Spanish Empire than subduing a Filipino insurrection.

In victory, the United States acquired Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines and annexed the peaceful island chain of Hawaii. McKinley also gained a new running mate in 1900, the nearsighted war hero of San Juan Hill.

The price was approximately thirty-three hundred dead American servicemen, lost primarily to viruses and bacteria rather than shells and bullets. Dysentery, malaria, typhoid, yellow fever, along with food poisoning from tainted canned beef killed just as many soldiers state-side as had fallen overseas. The United States would also choke on a chain of islands. After granting Cubans their freedom, McKinley decided to “civilize” the Filipino people and turn their vast archipelago into a protectorate. The caustic endeavor would result in the longer and deadlier P

HILIPPINE

A

MERICAN

W

AR

and push the United States into its own era of imperial rule.

76

The Spanish-American conflict produced an overload of media sensationalism. The worst perpetrator of yellow journalism was the owner of the

New York World

, Joseph Pulitzer, who would later establish an award for outstanding achievement in news reporting.

6

. WOODROW WILSON (SECOND TERM)

FIRST WORLD WAR (1917–18)

“Why, by interweaving our destiny with that of any part of Europe, entangle our peace and prosperity in the toils of European ambition, rivalship, interest, humor or caprice?” George Washington’s Farewell Address never seemed more logical than in 1917, when Europe’s royal houses were attempting to cure medieval hate through modern warfare.

To his credit, Woodrow Wilson avoided the vortex for three years. He even forbade the general staff from drawing up plans for mobilization, lest they create some self-fulfilling prophecy. Yet when Germany resumed unrestricted submarine offensives on all Atlantic traffic in February 1917—and issued its bumbling “Zimmermann telegram” a month later, offering Mexico support if it attacked the United States—the cautious Wilson had few options but to call for a declaration of war.

77

The president knew combat on a personal level. As a little boy in Civil War Georgia, he wrapped bandages for the stumps of soldiers, and he saw the devastation wrought by armies scything through farm-steads and villages. In entering a conflict far worse than the Brothers’ War, Wilson proceeded with a tangible sense of dread: “It is a fearful thing to lead this great peaceful people into war, into the most terrible and disastrous of all wars; civilization itself seems to be in the balance.” He was not exaggerating. By 1917, the Great War had become the deadliest in human history. But the time had come for the United States to end it.

78

Wilson did not conduct himself as a beacon of justice, suppressing basic civil rights through the S

EDITION

A

CT OF

1918. But he did understand the concept of total war, establishing executive boards to direct the country’s growing industry—the Shipping Board, the War Industries Board, plus commissions for food, coal and petroleum, and railroads. He also established the first military draft since the Civil War. In less than a year, the army was able to conscript, equip, train, supply, and transport two million doughboys (including artillery officer Harry Truman) directly into the European theater. Heralded as a “War for Democracy,” it was more to end the interminable butchering along the western front and to liberate the Atlantic Ocean from trade-killing torpedoes.

79

Wilson’s choice for field commander, Gen. John Pershing, may not have been the wisest. “Black Jack” had failed to subdue the insurgent Pancho Villa in 1917, and in Europe, he displayed an outdated faith in frontal assaults. But he did insist on keeping the American Expeditionary Force together rather than feed it piecemeal into the depleted ranks of the British and French armies. By 1918, the sheer weight of the U.S. contingent began to tip the scale in favor of the Allies. While Germany had not lost a foot of its own territory, sea blockades were starving it from the inside, and the front lines were bleeding it dry. A massive Allied assault upon the well-defended woodlands of the Meuse-Argonne in September 1918 cost American families nearly twenty-seven thousand dead in a few weeks, but it broke any chance of the German Empire’s lasting through the winter. An armistice on November 11 closed the slaughterhouse for good.

The price had been high—fifty-three thousand American dead from combat and more than sixty-three thousand consumed by disease. But in a little over a year, the United States had stopped a war that was killing an average of four hundred thousand human beings per month. Millions were being maimed or starved to death. At least eight million European children were orphaned by the time the shooting stopped. Though the United States would not be a part of it, the president’s dream of a League of Nations did come to fruition. Viewed as a failure, the peace did bury the warring empires of Austria, Germany, Russia, and the Ottomans, and the Atlantic was once again free.

80

Though the fighting abated in November 1918, the dying did not. In their lungs, veterans of all nations returned to their homes carrying the pandemic Spanish influenza, which proceeded to kill twenty million people worldwide, including a half-million Americans.

7

. DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER

KOREA (1953)

The dominant issue of the 1952 election was the bloody stalemate in Korea. Truman’s changing objectives, the futility in negotiations, and the mounting death toll (125,000 U.S. dead, wounded, missing, or captured by Election Day) doomed the Democrats to a landslide loss. Ike sealed his victory weeks before the polls opened by offering a solution to the Asian deadlock: “I shall go to Korea.”

81

Simple in dress and speech, Eisenhower sincerely wanted to be liked. When he smiled, which was often, his bright Kansas grin spanned the entirety of his friendly face. But there was something about the West Point graduate that struck people the moment they met him. He was efficient, no-nonsense, and he could get things done, mostly by way of relentless, prudent teamwork.

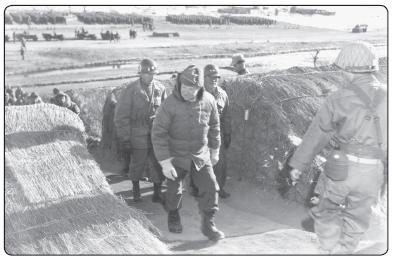

He kept his promise to see the Korean Peninsula for himself and to push the negotiations forward (the largest impasse being repatriation of POWs). Upon his arrival, the former general was struck by the unforgiving mountainous terrain, the same kinds of geological obstacles that had pinned the Allies for so many years in Nazi-occupied Italy. Continuation of the same old conventional strategy was not going to break the Chinese-anchored North, Ike surmised. The only option left was to hold tight on the ground, look for an end-run in negotiations, and prepare to use nuclear weapons.

By May 1953, atomic bombs were forwarded to bases in Okinawa. The first nuclear artillery piece, “Atomic Annie,” was successfully test fired later that month at the Nevada Test Site. Meanwhile, officials in India began to work as mediators between Beijing and Washington, hinting at the possibility that Eisenhower would initiate nuclear strikes if China did not cooperate.

82

As he promised during his campaign for the White House, President-elect Dwight Eisenhower visited the war zone of Korea. The arduous terrain and grueling stalemate convinced him that a continuation of the conflict would be pointless for both sides.

Eisenhower Library

Until the Beijing archives indicate either way, it is not yet known whether the nuclear threat or cumulative exhaustion broke the deadlock, but both North Korea and its Chinese allies agreed to a cease-fire in July. After six months in office, Eisenhower was able to fulfill his objective of ending the war with the existing boundaries of the two Koreas intact—without having to employ atomic devices.

Though a painful and costly struggle, the conflict had an unexpected benefit for the American military, namely, it never substantively downsized again. After every major conflict, the U.S. government traditionally dismantled its army and mothballed its navy, often by 90 percent or more, as was the case with the Civil War and the two world wars. By 1948, Truman had reduced the defense budget to less than fourteen billion dollars per year. After Korea, the Eisenhower administration funded the Pentagon at more than forty-five billion dollars annually.

83

Among the troops Ike visited in Korea was his own son John, who was serving as an infantry officer near the front lines. He survived to become an accomplished historian and diplomat. John Eisenhower is also, to date, the last child of a president to serve in a war.

8

. JOHN ADAMS

QUASI WAR WITH FRANCE (1798–1800)

In the innate antagonism between France and Britain, the ethnically English John Adams always felt closer to the latter, and his country had commercially drifted back to her after achieving independence. The shift had pushed the “eternal ally” France to hire privateers, basically pirates, to raid U.S. merchant ships at will. In 1796 alone, French cruisers and raiders had plucked more than three hundred out of five thousand American vessels from the sea, mostly in the Caribbean. The following year brought more of the same, and the United States began to struggle from lack of trade.

84

His cabinet, his country, and his wife were calling for all-out war against the tempestuous French. But Adams knew his people were vulnerable. They had won their Revolution in large part because they were able to play the two superpowers against each other. At present there was no such opportunity, and to fight alone against either one would likely mean that Adams would be the last president of a short-lived United States.

Playing every angle, Adams coldly suppressed dissent at home through the A

LIEN AND

S

EDITION

A

CTS

and tried to maintain open channels of diplomacy in the illfated XYZ A

FFAIR

. At the same time, he prepared to fight if needed, and for that he has been rightly called the “Father of the Navy.”