History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (20 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

When all was done, the president did lose his birth state of Kentucky, plus Delaware and McClellan’s New Jersey. The popular vote was close—a little over 2.2 million to 1.8 million. Lincoln narrowly won New York. Of nearly 750,000 votes cast in the state, he edged Mac by 6,749. Yet a sweep of the Northeast and Midwest gave the incumbent a decisive count in the Electoral College, bolstered in part by massive support from the troops. Seventy-eight percent in blue went with their president. The decisive mandate devastated McClellan. “For my country’s sake,” he wrote to a friend, “I deplore the result.”

54

Shortly after his stinging defeat in the 1864 election, George McClellan left the United States for Europe and stayed away for three years.

9

. 1980

| RONALD REAGAN (R) | 489 |

| JAMES CARTER (D) | 49 |

Ten Republicans entered the starting gate, chomping at the bit to race against a hobbling Ford administration. Among the candidates was Ronald Reagan, who many dismissed as too old at sixty-nine to be a genuine contender. Yet Reagan’s acting background, the very butt of political jokes, became his most valuable asset in the audition for leading man.

“Dutch” knew how to draw sympathy, recounting his family’s hardships in the Great Depression, his life as a soldier in World War II (albeit on sound stages in sunny California), and his conversion to the Republican Party (after voting for FDR four times and Truman once). Though Reagan was upstaged in the first act, losing the Iowa Caucus to Texan George H. W. Bush, he came back with vigor in the subsequent primaries. By convention time, the actor won the nomination on the first ballot.

Carter also won his party’s nomination on the first count, yet he was still plagued by inflation above 12 percent, interest rates hitting 20 percent, stifling energy shortages, and a Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Dwarfing them all was a lingering hostage crisis in Iran, destined to reach its first anniversary on Election Day 1980.

Ironically, the militant Islamic takeover of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran marked a highpoint in Carter’s approval ratings, as the nation rallied around its leader in the early days of the standoff. But as weeks turned to months, and only a few of the sixty-nine American citizens and diplomats were released, Carter’s numbers began to slip, from nearly 60 percent down to the low 30s. Polls indicated that participants were more likely to vote against Carter rather than for Reagan, whose popular messages of patriotism came with frequent miscues, such as insisting that trees caused pollution and labeling the Vietnam War as a “noble cause.”

55

Weeks before the November showdown, analysts predicted a close race.

Newsweek

had the Georgian edging out the Californian. Yet when Election Night arrived, many former Carter supporters stayed home, while last-minute undecideds voted predominantly for the alternative.

56

Carter took Georgia’s twelve electoral votes, plus five smaller states. Many Democrats lamented the presence of third-party candidate John Anderson of Illinois, who collected 5.7 million votes, or 7 percent. Had all of Anderson’s supporters turned to Carter (unlikely because Anderson was a former Republican), the president would have taken sixteen states, none of which rivaled the Reagan-Bush trophies of California, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Texas.

57

In a bittersweet moment for the incumbent, the American hostages in Iran were freed on the very day of Reagan’s triumphant inauguration.

James Carter was the first incumbent Democrat to lose the White House since Grover Cleveland in 1888.

10

. 1964

| LYNDON B. JOHNSON (D) | 486 |

| BARRY GOLDWATER (R) | 52 |

Riding a wave of sympathy from the assassination of John F. Kennedy in Dallas, Lyndon Johnson easily secured the official blessing of his party at the 1964 convention in New Jersey. Submitting his name for nomination was Texas governor John Connally, who was still recovering from the bullet that had first passed through Kennedy’s neck. Amid the convention’s tributes to the late president, LBJ stopped short of naming Robert Kennedy as his running mate. Later on, Johnson said that young Robert had “skipped the grades where you learn the rules of life.” He instead chose the equally liberal Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota, assuring his base of support that Jack Kennedy’s pledge of social reform would remain intact.

58

Offering a countermeasure, Republicans nominated archconservative Barry Goldwater. Born in Arizona when it was still a territory, Goldwater was a living artifact of the Old West. Rough-hewn in thought and appearance, he stressed rugged individualism as the cure to society’s ills. Congressman William Miller of New York became his running mate, despite receiving zero delegate votes at the national convention in San Francisco.

Goldwater, a.k.a. “Mr. Conservative,” condemned civil rights legislation as reverse discrimination. Also voting against the censure of Joseph McCarthy, Goldwater insisted that the senator’s hunt for communists made the United States a “safer, freer, more vigilant nation.” In accepting his party’s nomination, he uttered the now famous “extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice,” a mantra backed by offhand comments endorsing the use of thermonuclear weapons in Vietnam.

59

In response, the Johnson campaign aired the controversial “Daisy Girl” commercial, showing a playful child’s world erased by nuclear war. Such scare tactics were politically unnecessary. Johnson’s approval ratings were holding steady at 70 percent, while unemployment, crime, and Vietnam still appeared to be manageable issues.

60

The election was never in doubt. Most voters found Goldwater too radical to be plausible. Though he did attain support from conservatives like Ronald Reagan, the senator also received unwanted endorsement from extreme rightists such as the John Birch Society and the jingoist “Americans for America.” Moderates, labor, and minorities voted overwhelmingly against him, and he barely won his home state. Looking back, one of Johnson’s speechwriters called the landslide of 1964 “one of the silliest, most empty, and most boring campaigns in the nation’s history.”

61

For vice president, Lyndon Johnson heavily considered naming Defense Secretary Robert McNamara.

It only takes a generation or two to turn a battle into nostalgia. Such is the case with presidential elections, when blood feuds are forgotten and all that remains are faded cartoons, quirky slogans, and kitschy buttons. Enter the next campaign, and the mudslinging seems uniquely vulgar, as if politics had never been so rabid.

In reality, elections have never been so lawful and civilized as they are at present. Parties have learned the risks of wiretapping, slander, and slush funds. Journalists employ fact checkers and fear committing libel. Never has campaign financing been so tightly monitored.

This evolution took time. At first there was just the voice ballot, when citizens stated their choice in front of potentially hostile bystanders. Paper balloting was no better, as parties printed their own forms, often using symbols and colors similar to their opponents’ in order to fool the illiterate. When polling did not go as they wished, district officials often “misplaced” whole boxes of returns. Much of this petulant behavior was exorcized by the secret ballot in the late 1800s. The first voting machines in 1892 marked a further decline in fraud.

62

Voting itself is more democratic than ever. In the first elections, fewer than one-fourth of white males could participate. By 1860, every state except South Carolina essentially had universal white male suffrage. Women won the right to vote in national elections in 1920, as did Chinese Americans in 1943 and Japanese Americans in 1952. A century after emancipation, the 1965 Voting Rights Act guaranteed the opportunity to all African Americans. Since the Bill of Rights, there have been seventeen amendments to the U.S. Constitution—more than half of which involve the expansion of voting rights.

When all is said and done, however, elections are still fundamentally competitions, some of which have beaten the better angels of our nature. Listed below are the ten most divisive presidential races in the nation’s history, based on the overall amount of civil unrest, voter fraud, vote tampering, media libel, and acts of public litigation that each generated. A testament to how far democracy has progressed, the majority occurred in the nineteenth century.

1

. “THE IRREPRESSIBLE CONFLICT”—1860

| ABRAHAM LINCOLN (R) | 180 | JOHN C. BRECKINRIDGE (SD) | 72 |

| JOHN BELL (U) | 39 | STEPHEN A. DOUGLAS (ND) | 12 |

The bloodiest war in American history did not start over the bombardment of a federal fort, nor during a pitched battle along the banks of Bull Run. Disintegration began immediately after a presidential election.

The chance of disunion had been present since the nation’s founding. Southerners George Washington and Thomas Jefferson sincerely feared it. Northerners Benjamin Franklin and John Marshall expected it sooner rather than later. Yet the experiment survived several economic breakdowns, rebellions of citizens and slaves, the burning of its capital, and a dozen wars. Crises came and went, while an unanswerable question lingered.

North and South, the vast majority of Americans owned no slaves, but most tolerated the institution as a deeply rooted reality. The spread of slavery was an entirely different issue, of which there seemed no middle ground. In the 1860 election, Northern Democrat Stephen Douglas argued for new territories to decide for themselves, a policy already invalidated by sectarian violence in Kansas. Southern Democrat John Breckinridge, the nation’s vice president, ran on a proslavery platform, while Unionist and former Secretary of War John Bell hoped that silence would win him the presidency. The Republican Lincoln flatly believed that all new states admitted into the Union should be free soil.

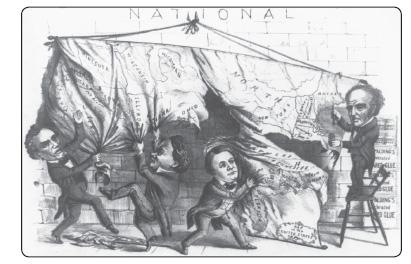

An 1860 nonpartisan cartoon depicts the four presidential candidates tearing the country apart. For once, sensational journalism was correct.

The four-horse race quickly devolved into a public stampede of slander, libel, and fraud. Month after month, parades, rallies, and the media played on base fears. Rumors spread that Lincoln was part black. Texas newspapers fabricated stories of slave uprisings to scare people into voting for Breckinridge. The pro-Bell

Richmond Whig

warned that a Breckinridge victory would bring “all the horrors of civil, social, and servile war,” and a Kentucky paper reported, quite falsely, that there was no use voting for him because he had a terminal illness. The

St. Louis News

printed fake poll numbers showing Bell winning the state by a mile, while in fact Douglas was far ahead in the polls. In New York City, thousands of Douglas supporters marched with signs denouncing the Republican Party, including one banner that read “free love and free n[—]s will certainly elect Old Abe.”

63

The country fractured soon after Election Day because the Republican won without receiving a single vote in ten states—all in the South. He even finished dead last in his birth state of Kentucky.

64