History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (16 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

Minor parties again played the role of spoilers. As with the Pro-Greenbacks and Prohibitionists in Tilden’s day, the environmental Green Party and the conservative Reform and Libertarian parties trimmed precious ballots from the two major contenders.

7

In 2000, Al Gore lost his home state of Tennessee. Not since Woodrow Wilson in 1916 had a candidate been defeated in his native state and managed to win the presidency.

4

. 1796

| JOHN ADAMS (F) | 71 | THOMAS JEFFERSON (D-R) | 68 |

| THOMAS PINCKNEY (F) | 59 |

In his Farewell Address (written with considerable input from Alexander Hamilton), the departing President Washington forewarned “the baneful effects of the spirit of party…It agitates the Community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot and insurrection.”

Published during the country’s first truly competitive election, the president’s advice went unheeded. Congressman Fisher Ames noted that, instead of having a calming effect, Washington’s address was “like dropping a hat, for the party racers to start.”

8

Though the newly forming Federalists and Democratic-Republicans were soon to grow into mortal enemies, their chosen candidates were less enthusiastic. In early December, as he awaited news of the outcome, Federalist favorite John Adams wrote to his son John Quincy, “I look upon the Event as the throw of a Die, a mere Chance, a miserable, meager Triumph to either Party.” For the irritable Adams, the embarrassment of losing outweighed the desire to win, as he longed to close a lengthy and arduous career that kept him far from home. So, too, retired Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson hoped to finish second or lower, often insisting, “I cherish tranquility too much.”

9

In an age when electors used their own discretion and long distances meant piecemeal information, the final tally took months to calculate. Observing from nearby Montpelier, James Madison wrote his friend Jefferson that he believed South Carolina’s soldier and diplomat Thomas Pinckney had won, with Adams finishing second. All would soon learn that a few key swing votes provided a completely different outcome. In heavily pro-Jefferson North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, one rogue elector from each state voted for Adams. The sitting vice president needed sixty-nine electoral votes to win; he took seventy-one.

10

Jefferson finished close behind with sixty-eight, and to the surprise of his devotees, the Republican decided to serve alongside the Federalist. In an attempt to reassure his political allies, Jefferson noted that subordination to Adams was neither dishonorable nor unfamiliar to him: “I am his junior in life, was his junior in Congress, his junior in the diplomatic line, his junior lately in our civil government.”

11

Adams would be the last president to serve in Philadelphia. Unbeknownst to him and his party, Adams would also be the only Federalist to ever be chief executive, and his long friendship with Jefferson was about to come to an unpleasant end.

The 1796 election marked the highest number of candidates ever to receive electoral votes—thirteen. Among them were George Washington, Samuel Adams, John Jay, Aaron Burr, and George Clinton.

5

. 1916

| WOODROW WILSON (D) | 277 |

| CHARLES EVANS HUGHES (R) | 254 |

As he opened the Republican Convention in Chicago, Senator Warren Harding made a plea for party unity, reminding his colleagues that defeat in 1912 came largely from their internal feud over William Howard Taft and Teddy Roosevelt. The assembly agreed and refused to nominate either one of their former presidents. The two men were not surprised. Contentedly teaching law at Yale, Taft knew his political career was “resting in a tomb.” Suffering from recurring malaria, TR also realized his time had passed. “The People as a whole are tired of me and of my views,” he observed.

12

The GOP instead backed former New York governor and presiding justice of the Supreme Court Charles Evans Hughes. From the venerable bench, the moderate Hughes could offer no direct comment on his political outlook, and thus he could offend no one. Upon receiving the unsought nomination, Hughes accepted and immediately notified the president of his resignation from the High Court. Democrats backed the incumbent Woodrow Wilson.

At the time, differences between Democrats and Republicans were minimal. Both sides promoted stronger defense, women’s suffrage, a ban on child labor, and closer ties with Latin America. The critical question involved warring Europe. Democrats backed their incumbent with the effective slogan, “He kept us out of war,” which was high praise from a nation repulsed by the abattoirs of Verdun and the Somme, the “innovation” of poison gas, and a death toll growing by millions. Also committed to neutrality, the Republicans openly questioned if Wilson was doing enough to protect American interests. Demanding greater mobilization and accelerated arms production, Hughes and his constituents appealed to those impatient for resolution to the world war.

On Election Night, the GOP strategy appeared to have worked. Early returns indicated a near sweep of the Northeast for Hughes, while the Virginia-born and Georgia-raised Wilson took the less populous South. Hughes went to bed assuming he had won, and New York papers began printing headlines of his triumph.

As precincts farther west submitted their results, momentum shifted to the Democrats. Wilson scored crucial wins in Ohio and Texas, most of the Plains states, all of the Rockies, plus Washington and Oregon. Everything then hinged on California’s thirteen electoral votes. By a scant thirty-eight thousand ballots, the Golden State went with Wilson. The president kept his job, but he would soon fail to keep his country out of war.

Charles Evans Hughes eventually reached the White House, serving as secretary of state to Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge. Appointed chief justice of the Supreme Court by Herbert Hoover, Hughes went on to become the only person to administer the oath of office to the same president three times—Franklin Roosevelt in 1932, 1936, and 1940.

6

. 2004

| GEORGE W. BUSH (R) | 286 |

| JOHN KERRY (D) | 251 |

The appearance of being “electable” has catapulted several back-markers to the front. In 1860, Republicans dropped Senator William H. Seward and former Ohio Governor Salmon P. Chase for being too outspoken against slavery, favoring instead a moderate one-term congressman from Illinois. In 1848, both the Democrats and the Whigs recruited Maj. Gen. Zachary Taylor, although he belonged to neither party. Preceding both the 1948 and 1952 elections, President Harry Truman privately asked Dwight Eisenhower to run for president as a Democrat.

13

Early in the 2004 campaign, the clear Democratic front-runner had been Howard Dean. A Vermont governor who oversaw eleven balanced budgets and two reductions of state taxes, Dean stood well clear of nine other candidates, with Missouri Representative Dick Gephardt a distant second. As the caucuses and primaries neared, Dean’s main rivals began to call him “unelectable,” primarily because of his vocal opposition to the 2003 invasion of Iraq. In a matter of days, his massive lead dissolved into an embarrassing third-place finish in the Iowa Caucus, behind Senator John Kerry of Massachusetts and Senator John Edwards of North Carolina. Within a month, Dean was out, and Kerry and Edwards went on to represent the party.

As it turned out, Kerry wasn’t quite electable either. When the senator criticized the war in Iraq, after voting to support the invasion, his critics labeled him a “flip-flopper.” The Catholic Kerry also vacillated when speaking of his religious convictions (a tightrope John F. Kennedy knew well). By comparison, Bush’s unwavering stance on his “global War on Terror” earned him points among those who favored decisiveness, while his patent evangelism brought him continued support from the religious Right.

On Election Night, Kerry initially did well, taking the entire Northeast, plus Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin. Then the South, Plains, and Rockies went to the incumbent. A late rally gave the Democrat the West Coast, and when reports came in that Ohio was experiencing widespread problems with voting machines, the contest looked like a replay of Florida in 2000. The day after the election, however, further scrutiny revealed that the margin in the Buckeye State was well over one hundred thousand votes in favor of Bush, enough to convince Kerry to abruptly concede the race.

14

George W. Bush won and lost almost the exact same states in 2004 as he had in 2000. The only differences in his reelection were first-time victories in Iowa and New Mexico and defeat in New Hampshire.

7

. 1884

| GROVER CLEVELAND (D) | 219 |

| JAMES G. BLAINE (R) | 182 |

Not since James Buchanan in 1856 had the Democrats won a presidential election, but they believed they had a winner in the incorruptible Grover Cleveland. Physically imposing at a beefy 280 pounds, tough, and honest, Cleveland rocketed through the political ranks in Buffalo. From ward supervisor, to assistant DA, to sheriff, to mayor, Cleveland ran his posts with iron-fisted efficiency. He could work thirty-six hours straight without sleep, hated yes-men, and openly attacked the party bosses of Tammany Hall. By 1884, he had risen to governor, where he championed the cause of political reform.

15

Running against him was GOP leader James Blaine of Maine. Even more vibrant and popular than Cleveland, he was known as the “Plumed Knight” for his patriotic rants against former Confederates, many of whom were Democrats. Twice he had run for the Republican nomination, and twice he lost narrowly to dark-horse veterans of the Civil War (Garfield and Hayes). In 1884, it was his turn to be president, and many assumed he would be, considering the Republican winning streak.

16

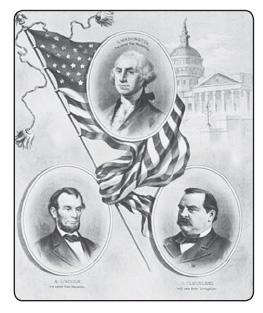

A Democratic poster in the 1884 election entitled “Saviours of Our Country” featured Washington, Lincoln, and Cleveland.

News that Cleveland had a premarital affair seemed to herald a Republican landslide. Polls showed the governor trailing in his own state by as many as fifty thousand voters. But Blaine made mistakes of his own late in the campaign, alienating Catholics in the North and former Confederates in the South (see C

ONTROVERSIAL

E

LECTIONS

).

The drastic shift in momentum cursed Blaine’s third and final try for the presidency. Despite taking most of the Midwest and all of the Pacific Coast, he was defeated in several key Republican states in the Northeast, and none more critical than Cleveland’s New York, which decided the election. In the Empire State, out of more than one million voters, Blaine lost to Cleveland by a miniscule 1,049 ballots.

17

James Blaine is the only presidential candidate ever to win Illinois, Ohio, and Pennsylvania and still lose the election.

8

. 1976

| JAMES CARTER (D) | 297 |

| GERALD FORD (R) | 240 |

Aside from the much-anticipated bicentennial Fourth of July at home and two successful

Viking

landings on Mars, the United States had little to celebrate in 1976. Lingering trauma from Vietnam and W

ATERGATE

, 10 percent unemployment, 12 percent inflation, and the unnerving weight of the thirty-year Cold War left the nation in a state of political fatigue. Consequently, Democrats and Republicans faced a mutual dilemma in the presidential campaign: how to motivate a highly disillusioned electorate.

The GOP had the advantage of incumbency, although the sitting president had not been elected. Representative Gerald Ford had fallen into the executive chair through Vice President Spiro Agnew’s resignation on charges of tax evasion and Richard Nixon’s painful abdication. After barely a month in office, Ford burned most of his political capital by granting Nixon a full and absolute pardon. Further eroding Ford’s image, he barely survived a nomination battle against archconservative Ronald Reagan.

18