History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (17 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

The opposition appeared just as troubled. From a herd of fourteen unexceptional candidates, the best the Democrats could offer was a former Georgia governor who had been elected out after one term. Presenting himself as a Washington outsider and devoutly religious, Jimmy Carter appealed to those wracked with Beltway skepticism. But his evasive stance on issues straddled the line between avoiding controversy and appearing indecisive. Appropriately, he finished a distant second in the Iowa Caucus, trailing a solid block who voted “Undecided.” At the party convention in New York, Carter won on the first ballot despite a strong “ABC” (Anyone But Carter) movement among his fellow Democrats.

In their first televised debate, both candidates verbally wandered, leaving many viewers disappointed and unsure. Subsequent debates allowed the struggling Ford, who had trailed by as much as 30 percentage points, to stage a last-minute comeback.

Election Day was far more exciting than the campaign. Carter took 40.8 million votes to Ford’s 39.1 million. Eighteen states were decided by 2 percent or less. Fittingly, the race came down to the large pool of last-minute undecideds, 61 percent of whom eventually went with the peanut farmer–nuclear physicist. Reflecting the national malaise already in place, voter turnout was 54 percent, the lowest since the Korean War.

19

President Ford’s campaign manager was his chief of staff, future Vice President Dick Cheney.

9

. 1848

| ZACHARY TAYLOR (W) | 163 |

| LEWIS CASS (D) | 127 |

Lewis Cass was a prolific writer from the prestigious Exeter Academy. Zachary Taylor had little formal education, rarely read, and had difficulty spelling. Cass had served as governor of the Michigan Territory, secretary of war, ambassador to France, and U.S. Senator. Taylor had never voted or held a political office in his life. The Democratic Cass wanted to be president. The independent Taylor insisted, “I am not at all anxious for the office under any circumstances.”

20

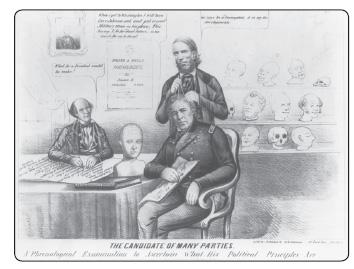

A phrenologist tries to determine the political disposition of the apolitical Zachary Taylor. Many guessed wrong about the slave-owning Southerner. As president, Taylor proved to be a diehard unionist who thoroughly distrusted the proslavery lobby, and he vowed to march on any state that threatened to secede.

The Whig Party didn’t care. They needed Taylor badly. They had opposed going to war with Mexico in 1846, and when the invasion turned out to be relatively short, victorious, and profitable, the Whigs went looking to adopt a war hero. Brig. Gen. Zachary Taylor, conqueror of Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna at the battle of Buena Vista, would do nicely. He reluctantly accepted their nomination.

On the single-most contentious issue of the day—expansion of slavery into the new territories—Taylor remained silent, despite owning more than a hundred human beings. In contrast, the Northerner Cass openly defended the constitutionally protected institution and encouraged settlers of newly acquired New Mexico, Arizona, and California to determine for themselves whether to allow slavery within their borders.

21

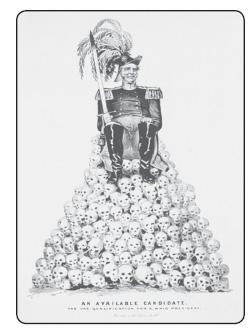

An 1848 Democratic broadside, “The One Qualification for a Whig Candidate,” shows a general atop a mound of human skulls. While the Whigs indeed courted Mexican War heroes such as Winfield Scott and Zachary Taylor, it was the Democrats who pushed for the military invasion of Mexico in 1846.

Cass’s diplomacy may have cost him victory. In response to his conciliatory tone, many antislavery Democrats ditched Cass and formed the Free Soil Party, nominating the aging former president Martin Van Buren as their candidate.

In the first presidential balloting to be conducted on a single day, the Free Soilers siphoned more than 10 percent of the popular vote, most of which came out of the Democratic pool. The largest, wealthiest, and oldest political party in the land, armed with the experienced Cass, lost to a weakened faction who ran a total political novice. Of all the disappointed Democrats, perhaps none was more so than the sitting president, James Polk, who said of the totally inexperienced Taylor, “The country will be the loser by his election.”

22

Each state of the Union has one prominent citizen represented in the National Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol Building. Michigan’s selection is Lewis Cass.

10

. 1960

| JOHN F. KENNEDY (D) | 303 |

| RICHARD M. NIXON (R) | 219 |

In the race between an eight-year vice president and a fourteen-year congressman, one of them vigorously embraced the revolutionary medium of television. That person, of course, was Richard Milhous Nixon.

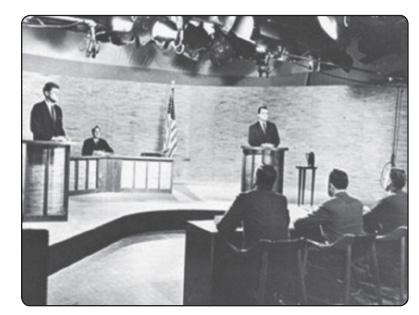

A considerable amount of lore surrounds the first televised presidential debate in U.S. history. In reality, the live face-off between the debonair Jack Kennedy and the dour Dick Nixon was the first such debate, period. Such tête-à-têtes were normally intraparty affairs conducted during primaries and were not popular with the candidates. The next set of presidential debates would not occur until 1976.

Certainly, the broadcast did signal a new age. When Nixon and Kennedy began their Washington careers back in 1946, scarcely one hundred thousand televisions existed in the entire country. On September 26, 1960, more than seventy million viewers tuned in.

Legendary was Nixon’s poor complexion—stemming from a recent knee operation and subsequent loss of twenty pounds. His ashen appearance and five o’clock shadow contrasted sharply with the fit and rested Kennedy. Yet polling indicated that the event was not decisive. In three televised debates that followed, the California Republican actually closed a considerable gap on his opponent.

As with any campaign, this one was contentious. Kennedy accused the Eisenhower administration of permitting “a missile gap” between the United States and Soviets. GOP ads claimed the Democrats had given up Eastern Europe, China, and atomic secrets to communists. Former president Harry Truman was especially harsh toward Nixon and predicted that Kennedy would “win overwhelmingly.”

23

It was possibly Nixon’s most ethical campaign. In an age when antipapal sentiments ran high, he refused to comment on Kennedy’s Catholicism. Aware of his opponent’s many ailments, including the potentially fatal Addison’s disease, Nixon declined to make health an issue, although he was just four years older than Kennedy and physically far stronger. He fulfilled a campaign promise to visit all fifty states, flying to Alaska just two days before the election and returning to the lower forty-eight in complete exhaustion. Some pundits hypothesized that his integrity may have won him Alaska but cost him several close races elsewhere.

24

On Election Day, as Kennedy canvassed the friendly Northeast, Nixon purchased an unprecedented four hours of television time at an ABC affiliate in California, answering live calls and promoting the GOP platform. The director of the Roper Poll had Nixon leading by 2 percent, but he confessed, “I have never seen the lead change hands so many times.” Gallup had Kennedy leading by 1 percent.

25

At the famous first televised debate, Richard Nixon embraced the medium with greater zeal than his opponent.

Nixon Library

As predicted, the result was close. Several days passed before the outcome was confirmed. California and Illinois were too close to call, and voter fraud was evidently rampant in the latter. The critical state proved to be Texas, which Kennedy narrowly secured through his selection of running mate Lyndon Johnson. Rather than ask for a recount, the fatigued and disheartened Nixon accepted the result and contemplated retirement.

Popularly perceived as the dawn of “Camelot,” the 1960 election actually saw more women, college graduates, and independents vote for Nixon than Kennedy.

“Landslide” did not enter the American lexicon until the late 1800s, yet lopsided wins in the Electoral College were already commonplace. In the nineteenth century, most of the presidential races were not close, and in the twentieth century, eighteen out of twenty-five victors received twice as many electoral votes as their opponents.

Constitutional framers believed the opposite would occur, that few if any contests would produce a clear winner. The deduction appeared sound, considering their environment at the time. Only one in two hundred Americans subscribed to a newspaper. States were united only in theory, as interstate travel meant weeks of slow, back-road, back-breaking, horse-and-carriage drudgery. Once more, there were no political parties to speak of, and thus no machinery to produce consensus candidates.

Anticipating their diffuse communities would produce a flock of entrants, the framers invented a system in which the voting population would act like a large nominating committee. Either through male suffrage or legislatures, states would choose electors, who would then vote for president. To prevent a contest between favorite sons, each elector would get two votes, one of which had to go to a person outside the state. Assuming no one candidate would gain the necessary majority, the House of Representatives would then select a winner from the top five.

Unforeseen by the Constitutional Convention, emerging political parties quickly dominated the selection process. Steady growth in literacy, newspapers, and technology further transformed relatively obscure contestants into household names. Only twice in two centuries would the House choose a president. In all other cases, the public drifted toward two or three front-runners. More often than not, one candidate would outdistance the rest by furlongs. Following, in terms of percentage of electoral votes, are the most conspicuous examples of landslides in over fifty presidential contests.