History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (22 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

A Federalist cartoon depicts Satan and a drunk Thomas Jefferson trying to pull down the federal government during the contentious campaign of 1800.

At the last possible moment, the system worked, and an eleventh-hour vote lofted Jefferson into the presidency. Departing First Lady Abigail Adams rejoiced that the crisis had finally subsided, but she agonized that it was all too temporary: “I fear America will never go through another Election without Blood Shed. We have had a paper War for six weeks past, and if the Candidates had not themselves been entirely passive, Rage and Violence would have thrown the whole Country into a Flame.”

79

Thomas Jefferson received his swearing in at Congress Hall in Philadelphia, only a few hundred meters from the Pennsylvania State House, where twenty-four years previous, Adams and Jefferson worked together on producing the Declaration of Independence.

5

. THE DARK HORSE AND XENOPHOBIA—1844

| JAMES K. POLK (D) | 170 |

| HENRY CLAY (W) | 105 |

With President John Tyler unwilling to follow party directions, the Whigs dropped him for congressional icon Henry Clay of Kentucky, the swaggering, persuasive master of negotiation. The race was to be Clay’s third try for the prize. Democrats struggled to choose between former president Martin Van Buren and states’ rightist John C. Calhoun. After forty-nine exasperating ballots, the diligent yet lackluster Speaker of the House James K. Polk became their compromise choice.

The campaign quickly settled into a battle of libel and slander. Democrats accused Clay of breaking “every one of the Ten Commandments.” Whigs painted Polk as a warmonger who was willing to fight Britain and Mexico to get Oregon and Texas. They also condemned Polk for being a slave owner (though Clay was one too). For much of the population, the issue of the day was neither slavery nor expansion. It was immigration.

80

In 1820, there were only about sixty thousand immigrants out of some ten million Americans. By 1830, the number of foreign-born had doubled. The following decade the total quadrupled, consisting mostly of impoverished European Catholics.

The influx prompted a rise of ultranationalism, mostly among evangelical Protestants, who blamed rising crime and falling wages on the “Papists” pouring in from the Old World. In the late spring of 1844, a small altercation between Americans and Irish in Philadelphia set off a week of brawls, shootings, and arson. When it was over, scores of shops and homes were destroyed, two Catholic churches lay in ashes, and seven people were dead. The violence spread to other cities, including Charlestown, Massachusetts, where arson leveled a Catholic convent. To assure “law and order” in the upcoming election, Nativists in several states tried to restrict voting to U.S.-born citizens.

81

Always the compromiser, Clay tried to play the middle ground. In turn, he was attacked from both sides. Protestants chastised him for courting Rome and immigration, whereas Catholics feared his running mate, Theodore Frelinghuysen, who advocated Protestant Bibles in public schools.

82

Polk avoided the issue of ethnicity altogether, concentrating instead on promoting an aggressive foreign policy. The Democratic dark horse handily won the election. Yet it is possible that Polk achieved victory because of immigration rather than in spite of it. In the critical state of New York, which Polk barely won, corrupt Tammany Hall had naturalized thousands of Europeans almost as fast as they were leaving the boats. Encouraged to vote for Polk early and often, they did. In New York City alone, voter turnout was a curious 115 percent, vastly in favor of the Democrat.

83

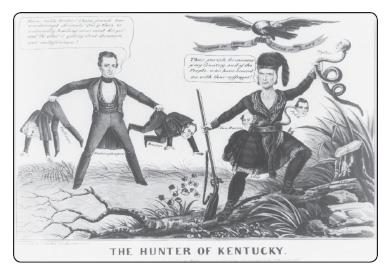

Henry Clay and Theodore Frelinghuysen hunt Democrats in this 1844 image. Frelinghuysen holds John C. Calhoun and Thomas Hart Benton, while Clay beheads Van Buren, Polk, and the sitting president, former Whig John Tyler.

In a failed effort to gain Irish votes among the heavily immigrant population, New York Whigs hinted that their candidate’s real name was “Patrick O’Clay.”

6

. “GESTAPO TACTICS”—1968

| RICHARD M. NIXON (R) | 301 | GEORGE C. WALLACE (I) | 46 |

| HUBERT H. HUMPHREY (D) | 191 |

For once, Nixon was not the center of a controversy. In the space of eight months, the Democratic Party went from dominating national politics to losing control of its own convention hall, and it all began in Saigon.

Vietnam looked winnable until January 30, 1968, when North Vietnamese forces launched the Tet Offensive. The following day, bloodied U.S. soldiers and marines were fighting hand-to-hand to retake their own embassy in the South Vietnamese capital.

Two months later, mentally and physically consumed by the war, Lyndon Johnson astonished the nation on live television with a sudden notice: “I shall not seek, nor will I accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your president.” On April 4, Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered outside a hotel in Memphis, and race riots broke out in Detroit and Washington, D.C. Months after that, leading antiwar candidate Robert Kennedy was gunned down immediately after he had won the California Democratic Primary.

Had the presidential election occurred a year before, Richard Nixon would not have won his own party’s nomination, let alone the presidency. But his promise to restore law and order in his country and make peace in Vietnam struck a chord with millions of Americans ready for a change. Democrats struggled to find a challenger, and at their national convention in Chicago, they quickly broke into two factions—those who supported the war and those looking for immediate withdrawal. Outside, thousands of antiwar protesters gathered, ranging from pacifists to radical leftists. To contain the crowds, Democratic Mayor Richard Daley mobilized the whole of the city’s police force and put the Illinois National Guard on high alert.

84

The tipping point came when prowar candidate Hubert Humphrey won the nomination on the first ballot, and crowds outside cried out in protest. In Grant Park, thousands of demonstrators and law officers started to turn on each other, and the violence immediately spread to nearby Lincoln Park. Rocks and tear gas incited panic on both sides. Bystanders were drawn into the ensuing chaos as police charged into the mobs, and rioting spread into the streets. Inside the convention hall, delegates watched in stunned silence as the riots were broadcast on live television. Horrified by what he was seeing, Senator Abe Ribicoff accused Richard Daley of “Gestapo tactics.” There were calls to dissolve the assembly. It would take Daley and his security forces more than twenty-four hours to restore order in the city.

85

The Democratic implosion in Chicago marked a national shift to the right. Though Humphrey rallied to make the election close—31.3 million votes to Nixon’s 31.8 million—his defeat signaled the end of an era. Before 1968, Democrats won seven out of ten presidential elections. Starting with Nixon, the GOP won seven out of the following ten elections.

86

Reflecting the deep racial tensions in the 1968 elections, independent candidate George Wallace ran on a platform of segregation. He subsequently won forty-six electors and nearly ten million popular votes.

7

. “BETWEEN LUST AND LAW”—1884

| GROVER CLEVELAND (D) | 219 |

| JAMES G. BLAINE (R) | 182 |

Mixing pulpit and politics, a reverend from Buffalo told his congregation that the upcoming election was a simple choice “between the brothel and the family, between decency and indecency, between lust and law.”

87

It is an incontrovertible truth that, from time to time, some Americans partake in premarital sex. Beer-drinking, cigar-smoking, and card-playing bachelor Grover Cleveland certainly did. While he was practicing law in Buffalo in 1873, he was practicing other skills with a widow, Maria Halpin. In 1874, she bore a son. Whether Cleveland was the actual father was a tertiary point for Cleveland, and he provided for the child through the ensuing years.

Running for president in 1884, Cleveland received the endorsement of the

New York World

on the basis of four qualities: “He is an honest man. He is an honest man. He is an honest man. He is an honest man.” But when a Buffalo newspaper leaked the story of Cleveland’s possible love child, the accusations flew. Papers called him a “moral leper,” “wretch,” and “libertine.” Cartoons showed a screaming baby with the title “Another Voice for Cleveland.” Apocryphal stories surfaced of attempted kidnappings to silence mother and child. Others morphed into eyewitness accounts of “Grover the Good” engaging in physical relations with harems of women.

88

Cleveland and his staff lessened the blow by readily admitting to the brief affair with Halpin and that he was providing financial assistance for the boy’s care. As bad as it was for Cleveland, Blaine had it worse, as stories surfaced that he had engaged in shady business deals with railroad corporations. The former secretary of state, House Speaker, and senator weathered months of deflowering editorials and mounting evidence. At one point, a rally of forty thousand gathered in New York City and shouted, “Blaine, Blaine, James G. Blaine, the Monumental Liar from the State of Maine!” Other chants were less tasteful.

89

Back and forth the sneers flew. When Nativists accused Blaine of being soft on Catholic immigration, a Protestant minister came to his defense, proclaiming the Republican stood firmly against “rum, Romanism, and rebellion.” The xenophobic endorsement cost Blaine dearly, especially among Catholics and Southerners. In response, Republicans spread fake reports that Cleveland was about to die from palsy or kidney failure. One rumor professed that he recently contracted contagious leprosy.

90

Rising out of the mud, Cleveland narrowly won (see C

LOSEST

E

LECTIONS

). He would run twice more, losing the White House in 1888 and regaining it in 1892. In each campaign he faced a new set of false accusations, among them stories that he was an alcoholic and that he beat his young wife.

91

Among the many “Mugwumps” in 1884—Republicans who voted for the Democrat Grover Cleveland—were Gettysburg veteran Carl Schurz, abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher, and author Mark Twain.

8

. CORRUPTION AND DEATH—1872

| ULYSSES S. GRANT (R) | 286 |

| HORACE GREELEY (LR) | VOTES WITHDRAWN |

Georgia’s former Confederate vice president, Alexander H. Stephens, viewed the candidates as a choice between “hemlock and strychnine.” Running for reelection was U. S. Grant, personally above reproach, but head of an administration that fostered the B

LACK

F

RIDAY

and W

HISKEY

R

ING

scandals.

92

The field of Democrats was so weak that they turned to a Liberal Republican,

New York Tribune

editor Horace Greeley. Later generations would know him for the quote “Go west, young man.” His contemporaries knew him to be intelligent but unwise, passionate to the point of irrational, and a veritable geyser of baseless accusations. During the Civil War, his

Tribune

equated Democrats with traitors, blamed unsuccessful Union generals for secretly backing slavery, and frequently accused Lincoln of cowardice. His words alone provided ample fuel for critics. His balding crown, rosy cheeks, frail glasses, and untamed neck beard made him a favorite of cartoonists. To his detractors, he had the look and sound of a panicky elf.

Yet the campaign was anything but comical, a sordid season the

New York Sun

called a “shower of mud.” Hard-right Republicans, claiming a monopoly on patriotism, depicted Greeley as soft on the South, while Grant was the triumphant warrior. Campaign photos invariably showed a much younger Grant in uniform.

93

Most cynical was the work of

Harper’s Weekly

illustrator Thomas Nast (inventor of the plump Santa, the Democratic donkey, and the Republican elephant). Nast and his fellow journalists portrayed Greeley as a servant of Jefferson Davis, based on the Confederate president’s early release from prison in 1867, which Greeley helped facilitate. They also accused the editor of being friendly to the Ku Klux Klan, a most puerile falsehood. The longtime abolitionist had adopted a forgiving tone toward the defeated Confederacy, yet he remained as repulsed as any by the prolific incidents of arson, intimidation, and murder infecting the South since the Klan’s birth in 1866.

94