History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (43 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

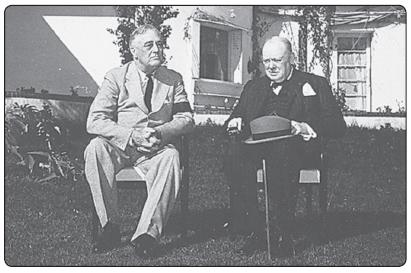

FDR and Churchill met at Casablanca in 1943. During a press conference at the summit, Roosevelt announced to the world that the Allies would not stop fighting until every Axis power had surrendered unconditionally.

It was Roosevelt who, in 1943, first declared the aim of unconditional surrender, providing a finite, definable, and shared goal previously lacking among the Allies. To achieve this grand strategy, he was neither haphazard (like Hitler), heartless (like Stalin), hesitant (like Churchill), nor a figurehead (like Hirohito). Throughout the conflict, the U.S. forces were the best fed and the best equipped, with twice the ratio of doctors to troops as the Germans or Soviets, three times the manpower of Britain, and ten times the combat survival rate of the Japanese.

63

Roosevelt would not live to see the end of this global conflict, nor would 405,000 of his fellow Americans in the second bloodiest war in U.S. history. Yet American losses were comparatively modest. Thirteen nations lost more soldiers and civilians. And despite fighting on two fronts, with allies of widely divergent goals, against two of the most powerful nation-states in modern warfare, the president was able to lead his nation to victory and leave it stronger than any other country still standing.

64

For every American killed in the Second World War, Japan lost nine, Germany lost seventeen, China lost thirty-five, and the Soviet Union lost sixty.

2

. JAMES K. POLK

MEXICAN-AMERICAN WAR (1846–48)

Some presidents make wars. Others have wars thrust upon them. James K. Polk willingly rattled his saber while running for office in 1844, vowing to plow into Mexico and the Oregon Territory if his foreign opponents did not concede to his territorial demands. In the end, the would-be warrior chose to charge at the lesser of two windmills, and his gains were unparalleled in the country’s brief history.

While he opted to negotiate a settlement over Oregon, he refused to accept the Mexican position that Texas ended at the Nueces River. Polk and his fellow Democrats argued that the southern border of

Tejas

stood at the Rio Grande, two hundred miles farther south, and stretched all the way north and west into modern-day New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming. Polk’s halfhearted attempts to buy the disputed area, plus New Mexico and California, yielded nothing but more hostility.

In a blatant show of force, “Little Hickory” sent a contingent of officers and men, under the direction of Brig. Gen. Zachary Taylor, to guard the “U.S.” side of the Rio. The event touched off a small battle and enabled Polk to ask for, and receive, a congressional declaration of war.

Polk’s preemptive strike against Mexico reaped huge benefits for his government. The ensuing peace treaty expanded the U.S. land area by a third and shrank Mexico to half its original size.

Polk wasted little time or effort reducing the unstable government of Mexico by initiating concurrent strikes on Santa Fe and Monterrey eight hundred miles to the southeast. Both cities fell, and within months, most of California was in U.S. hands. The following spring brought an amphibious assault upon Veracruz on the Gulf of Mexico. Driving west toward the Halls of Montezuma, Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott, assisted by able field officers such as Capt. Robert E. Lee, captured Mexico City by early autumn.

At the cost of thirteen thousand American dead (half the losses of their opponent), plus fifteen million dollars offered in compensation for lost lands, the United States grew by a third and reduced the size of Mexico by half. The degree of success was so great that an “All Mexico” movement grew in the United States, calling for the acquisition of the entire country, plus additional territory in the Caribbean and South America.

65

A higher proportion of Congress voted for the declaration of war against Mexico in 1846 (93 percent) than did against Germany in the First World War (89 percent) or against Britain in 1812 (61 percent).

3

. HARRY S. TRUMAN (FIRST TERM)

PACIFIC WAR (1945)

In the summer of 1945, American journalists stationed in the Pacific were betting on when the war would end. The earliest estimates were 1946. For troops leaving San Francisco for the Pacific theater, the optimistic phrase was “Golden Gate in ‘48.” Even with the fall of Okinawa in late June, the military high command in Tokyo was planning to fight into the indefinite future.

66

Harry Truman felt differently. He had first learned about the Manhattan Project and its “cosmic” or “atomic” devices in late April 1945, twelve days into his presidency, and he had known from his first reading of the top-secret reports that he was going to use them. The possibility of a shortened war seemed even brighter by mid-July after the Trinity Test in Alamogordo, New Mexico. Truman was in the aristocratic Berlin suburb of Potsdam when he received word of the successful detonation.

67

From its inception, the Manhattan Project aimed to build several prototypes in an effort to find a reliable design. Two promising models emerged: one a sphere of plutonium compressed to critical mass (the Trinity type), and the simpler but less stable “Little Boy,” which slammed two subcritical pieces of Uranium 235 together. When the project first began in 1939, Franklin Roosevelt envisioned the super-weapons as an unassailable additive to conventional forces. In 1945, Truman believed the same, as did Gen. George Marshall and Secretary of War Henry Stimson. An invasion of Japan was set for November, but the bombs would start falling as soon as they were ready.

It is true that the cabinet of Prime Minister Suzuki Kataro wanted a cease-fire in the summer of 1945, but they were wholly against surrendering. Japan volunteered disarmament, yet insisted it would disarm itself. There was to be no foreign occupation, nor a replacement of the government. In addition, the empire was to retain Formosa, Korea, and Manchuria, encompassing three times the land and twice the population of Japan proper.

68

The Allies refused. Conventional bombing of Japan’s main islands continued, and the uranium device was prepared for use. To give the impression that the United States had a whole arsenal of ultraweapons, Truman ordered the destruction of Hiroshima on August 6, followed immediately by a public statement: “We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city.”

69

When no word came of unconditional surrender, the president ordered the second device dropped on August 9, burning much of Nagasaki. Preparations were fast underway to assemble a third and fourth bomb when Tokyo capitulated.

Truman gambled and won. Fire and irradiation killed 170,000 in two cities, but it was a fraction of what Japan had already lost through incendiary bombings. Both sides were experiencing an exponential increase of losses as the United States neared the main islands. Manila alone cost 11,000 American and Japanese dead. Iwo Jima killed 25,000 altogether. Nearly 200,000 soldiers and civilians on all sides died in Okinawa. Estimates of a half-million casualties through the coming invasion were conservative, and the war would likely have ended no sooner than 1947.

70

Japan’s Minister of War Anami Korechika, previously committed to fight on after Hiroshima, feared the Americans had “one hundred atomic bombs” after he learned of the loss of Nagasaki.

4

. GEORGE H. W. BUSH

FIRST GULF WAR (1990–91)

George H. W. Bush could be pragmatic. For years the United States had backed Panama strongman Manuel Noriega. But when the diminutive general became closely associated with drug cartels, negated the 1989 Panamanian elections, and installed a crony as president, he became the target of a U.S. invasion. Under Bush’s orders, Noriega was deposed, caught, and extradited for trial. It only took the U.S. armed forces a few weeks to complete the mission.

Bush could be compassionate. Food shortages and warlords reduced Somalia to a state of famine in 1992. The lame duck Bush ordered twenty-five thousand troops into the east African nation to secure the delivery of relief supplies. The operation saved possibly thousands of lives, and Bush made no attempt to turn the rescue mission into a permanent police force.

He also knew how to liberate a country. On August 2, 1990, Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein invaded the nation of Kuwait. Smaller than New Hampshire, Kuwait was monarchial, wealthy, and not the friendliest country toward Washington, but it was nonetheless a sovereign nation and a key piece to the political stability and oil production of the Gulf. Judiciously, diplomatically, with the assistance of Secretary of State James Baker III and the N

ATIONAL

S

ECURITY

C

OUNCIL

, Bush assembled the largest coalition of armies since the Second World War. Thirty nations amassed seven hundred thousand servicemen and women altogether, most of them American. A widely supported UN resolution demanded that Iraq withdraw by January 15, 1991, or face a military expulsion.

Ideally, Bush wanted an Iraqi withdrawal. Casualty estimates for the United States alone numbered in the tens of thousands. In a letter to his children, the president expressed a sincere desire that war could be averted. His worst fear, he wrote, was that a war would devolve into a protracted stalemate and an indefinite occupation. If that were to occur, he said, his impeachment was all but inevitable.

71

Bush did not have to worry. A month-long bombing campaign decimated a poorly led, poorly equipped, unmotivated Iraqi army. A multinational invasion in February needed only one hundred hours to crush Hussein’s forces and liberate Kuwait. A cease-fire quickly took hold, and within four weeks, the Bush administration began withdrawing U.S. troops from the area. The entire affair lasted seven months. In terms of lives lost, the entire coalition experienced fewer than four hundred deaths. The financial commitment was approximately sixty-one billion dollars, most of which was paid by Kuwait.

72

Despite its success, the war was not viewed as a great triumph. Exercising his trademark restraint, George Herbert Walker Bush refused to placate the hawks who wanted a full-scale invasion and the overthrow of a blowhard tyrant. In a rare instance of history answering “what if,” Bush’s eldest son decided to play out the invasion scenario in 2003. The result was almost exactly what George H. W. Bush had predicted in his memoirs, written years before George W. Bush was ever a presidential candidate:

I firmly believed that we should not march into Baghdad…To occupy Iraq would instantly shatter our coalition, turning the whole Arab world against us, and make a broken tyrant into a latter-day Arab hero. It would have taken us way beyond the imprimatur of international law bestowed by the resolutions of the Security Council, assigning young soldiers to a fruitless hunt for a securely entrenched dictator and condemning them to fight in what would be an unwinnable urban guerrilla war. It could only plunge that part of the world into even greater instability and destroy the credibility we were looking so hard to reestablish.

73

Number of U.S. troops killed in the First Gulf War: 297

Number of U.S. troops killed in the Second Gulf War: 3,800+

5

. WILLIAM McKINLEY

SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR (1898)

To destroy an empire in a few months is no mean feat, and President McKinley did not want to do it in the first place. Before the Republican ever took office, it was clear that Cuba, the Caribbean jewel of the Spanish Empire, was nearing a point of total collapse. Years of imperial oppression and corruption had decimated the colony, causing widespread starvation and revolts. By the end of 1897, one in six Cubans—nearly a quarter of a million human beings—were dead from emaciation or plague. In the United States, farmers in the Midwest empathized with the plight of Cuba’s rural poor, while investors in the Northeast salivated at the growth potential of the island’s plantations, mines, and railroads.

74