History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (28 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

While he was a New York assemblyman, Theodore Roosevelt helped craft a Tenure of Office bill. It was vetoed by his governor in earnest. “Of all the defective and shabby legislation which has been presented to me this is the worst,” wrote Governor Grover Cleveland.

7

. RONALD REAGAN (78)

REGULAR VETO: 39

POCKET VETO: 39

OVERRIDDEN: 9

Presenting himself as a conservative crusader against a spendthrift Congress, the fortieth president actually demonstrated considerable restraint. Ronald Reagan could talk a good game, but he personally hated confrontation, and he chose few battles. Rather than rule by veto, he preferred to sway Capitol Hill through less belligerent tactics, such as budget proposals and public appeals.

Congress consented to his demands for an expanded military. In turn, he shelved plans to eliminate the Small Business Administration, permitted over six hundred million dollars per annum for the Job Corps, and backed away from his campaign promise to eliminate the cabinet post of Secretary of Education.

59

Few of his vetoes went unchallenged, and when Reagan tried to reject bills for health and human rights, he usually lost. He denied two extensions of the Clean Water Act, research funding for the National Institute of Health, and extensions to several civil rights laws. Congress passed each one anyway. On foreign aid, Reagan rejected a bill that mandated protection of human rights in a military aid package for El Salvador (the veto was later reversed by the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals). The following session, he vehemently opposed sanctions against the apartheid government of South Africa, arguing for a less belligerent approach. Congress overruled him.

60

In one of his more controversial moves, Reagan lobbied to sell one hundred antiship missiles, hundreds of small antiaircraft weapons, and more than one thousand Sidewinder missiles to the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Congress volleyed back with a joint resolution to stop the sale, which Reagan vetoed. Noting Saudi Arabia’s tacit connections with Syria and the Palestinian Liberation Organization, the Senate once again moved to override Reagan’s negative. This time the Gipper won—by a single vote.

61

Among the politicians who publicly supported Ronald Reagan’s sale of arms to Saudi Arabia was former president Jimmy Carter.

8

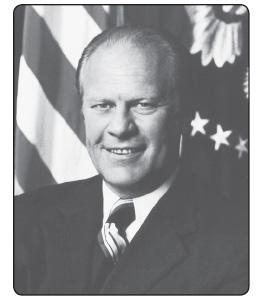

. GERALD FORD (66)

REGULAR VETO: 48

POCKET VETO: 18

OVERRIDDEN: 12

Gerald Ford contended, “The veto’s not a negative thing…And a president ought to use it more freely if he doesn’t like what Congress is doing…The only way you’re going to get the budget under control is for a president to establish whatever priorities he believes in, fight for them, and veto, veto, veto.”

62

Several of Ford’s deputies were less comfortable with his confrontational approach against a Democratic Capitol Hill. As one aide saw it: “No president can afford to veto twenty-five bills a year…It’s too damn much, and Congress won’t stand for it.” Congress, in fact, did not stand for it. Legislators officially challenged more than half his regular vetoes and successfully reversed twelve of them. In the history of the presidency, only Andrew Johnson and Harry Truman experienced an equal or greater number of overrides.

63

Several vetoes appeared rather callous on the surface, yet the fine print often revealed a compassionate rationale. Ford refused additional funding for the Rehabilitation Act, which provided vocational training to the handicapped, because it added 250 bureaucratic positions to the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare yet reduced services to its clientele. He tried to stop a new G.I. Bill from giving Vietnam veterans more money for schooling because the allotment was disproportionately higher than what Korean War and World War II veterans received. Ford also rejected a National School Lunch Act, as it subsidized families who were above the poverty level and cost billions more than a program he introduced months earlier.

64

One veto in particular proved costly. In accepting the presidency, Ford vowed “openness and candor” with the American public, and two months later he blocked an enhancement of the Freedom of Information Act. He rejected it on the advice of staffers Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney, who believed the bill posed a national security risk. Ford agreed, though he knew there was bound to be resistance. True to his prediction, citizens grilled him in editorials, Democrats on the Hill rebuked the “undue secrecy in government,” and Congress negated his veto by a landslide.

65

Gerald R. Ford established a reputation of blocking Congress at every turn, despite the fact that he had served in the House for nearly a quarter-century.

Though Ford was aggressive with Congress, he never lost his sense of modesty. Among his pocket vetoes, Ford refused a bill that would have renamed a government building in Grand Rapids, Michigan, the Gerald R. Ford Federal Office Building.

9

. CALVIN COOLIDGE (50)

REGULAR VETO: 20

POCKET VETO: 30

OVERRIDDEN: 4

Legend contends that a woman attending a White House dinner said to Calvin Coolidge, “I made a bet today that I could get more than two words out of you.” The president replied, “You lose.” So goes the image of the thirtieth president.

In reality, “Silent Cal” was far more complex. He despised small talk, his 1925 inaugural speech is the fifth longest on record, and he held more press conferences than any chief executive before him. Far from laissez faire, he often resisted Congress, though his party was in the majority for the whole of his administration.

In some cases, denials were effortless. One bill offered pensions to war widows and their dependents who lost loved ones in the War of 1812. Coolidge lost no sleep in his veto because the war had been over for 110 years. Other vetoes came with risk and trepidation. Twice he alienated struggling farmers by refusing to have the government buy their surplus grain.

66

His most fateful veto came against the 1924 Bonus Bill, which was designed to provide monetary compensation for those who served in the Great War while their countrymen found lucrative jobs in their absence. Coolidge endorsed a similar law while governor of Massachusetts, but he thought it would only create ill will on a national scale, so he rejected it. He was overturned, and as he feared, the law caused problems. In 1932, destitute veterans marched as a Bonus Army upon the national capital and demanded immediate payment from Coolidge’s successor, Herbert Hoover. As thousands of men and their families began to build shantytowns throughout Washington, asking for money the government did not have, Hoover felt compelled to drive them out by bayonet, a miserable task executed by officers such as Maj. Gen. Douglas MacArthur and Majs. George S. Patton and Dwight D. Eisenhower.

During Coolidge’s five-plus years in office, Congress overrode four of his vetoes all on the same day.

10

. GEORGE H. W. BUSH (44)

REGULAR VETO: 29

POCKET VETO: 15

OVERRIDDEN: 1

In rhetoric, George H. W. Bush was less belligerent toward Congress than his old boss. In practice, he was more aggressive, particularly with his use of vetoes. He also enjoyed a higher success rate. Except for a few budget proposals, Bush was officially challenged on every one of his regular vetoes, and he won every time, with the exception of a minor bill involving cable television providers.

Yet his victories damaged him politically. Bush vetoed the Family and Medical Leave Act, though nearly 70 percent of the American public supported the bill. He offended the working poor by blocking a measure to raise the minimum wage. He gave the impression of being antidemocratic when he blocked a voter-registration initiative, and he looked worse when he vetoed sanctions against China after the Tiananmen Square Massacre. Though highly successful in a war against Iraq, Bush was less appealing in domestic affairs, and his “rule by veto” left voters wanting someone more progressive in the presidential election of 1992.

67

Though George H. W. Bush engaged the veto often, his president son did not follow in his footsteps. George W. Bush served his first four years without rejecting a single bill, the first chief executive to go an entire term “sans veto” since John Quincy Adams.

The Supreme Court began as an afterthought, formed during a marginal amount of discussion in the Philadelphia Convention, and explained in a handful of paragraphs in the Constitution. When Washington, D.C., was built, the third branch of the government wasn’t even given a building of its own. The high court initially resided in various rooms beneath the House and Senate, relocating no fewer than six times. Justices had no bench per se, nor private chambers. Not until 1935 would they receive their present stately abode, 146 years after the Court was born.

68

For a body so clearly marginalized in the early going, it has demanded and received a remarkable level of respect. Presidents often disagree with its decisions but will rarely risk direct confrontation. As demonstrated by the following cases, when the Executive and Judiciary branches have gone head to head, the Court usually wins. With a comparatively tiny budget and no military force, justices can still bring presidents to heel, in part because the two branches empower each other.

Presidents nominate justices to lifetime positions. In turn, justices often refrain from negating executive actions, especially ones supported by the public. For example, Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, and Lyndon Johnson’s Gulf of Tonkin Resolution were all technically unconstitutional. But the courts chose to exercise prudence for the sake of practicality.

Yet there have been clashes in the past, where checks and balances devolved into turf wars. Nearly all of them involved presidents with backgrounds in law, many of whom felt qualified to question the will of the justices. Following in chronological order are ten landmark battles that have strained, as well as defined, the relationship between the White House and the Black Robes.

1

. MARSHALL CLAIMS THE CONSTITUTION

MARBURY v. MADISON (1803)

President Thomas Jefferson and Chief Justice John Marshall honestly loathed each other. In private, Jefferson once called the authoritarian Marshall a man of “profound hypocrisy” and a member of “the Alexandrian party and the bigots and passive obedience men.” The Federalist in turn considered the disheveled Republican “unfit” to be president. Their disagreements were frequent and deep, and one established a legal precedent of monumental consequence.

69

Before John Adams departed the presidency, he made several late judicial appointments, all of them Federalists. A like-minded Senate approved them before retiring. The final step required the secretary of state to deliver the appointments, a task only partially completed in the forty-eight hours left in the Adams administration. When faced with the unsent appointees, newly sworn President Thomas Jefferson chose not to send them. Instead, he cut several of the posts out of the judiciary altogether, believing that a smaller government was a better one.

70