History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (29 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

Several of the eliminated appointees complained bitterly, including William Marbury, who was looking forward to being Justice of the Peace for Washington, D.C. Marbury sued to have the new state secretary, James Madison, deliver his employment papers, but neither Madison nor Jefferson were eager to obey his demands.

Jefferson despised Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall with all his being, but as president he could never bring himself to stand up against the dominant jurist.

When the case reached the Supreme Court, Chief Justice Marshall knew he had no legal authority to force the executive branch, and his nemesis, Jefferson, to give Marbury a job. But he also did not want to hand Jefferson a victory and rule in his favor. Instead, Marshall took the opportunity to define the separation of powers and stake a major claim for the judicial branch.

In a majority decision, he ruled that the Court did not have jurisdiction over the duties of the executive. But Marshall proclaimed that the executive and legislative branches could not interfere with the one great responsibility inherent in the courts—the right of “judicial review.” From that point onward, the judiciary alone had final say as to what was constitutional and unconstitutional. “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is,” wrote Marshall, and neither Capitol Hill nor the White House could ever deny that authority so long as the United States existed.

John Marshall established the tradition of having Supreme Court justices wear black robes. John Jay, the first chief justice, preferred red.

2

. THE BURR CONSPIRACY AND EXECUTIVE PRIVILEGE

UNITED STATES v. BURR (1807)

As a rule, the government does not care much for treason, and when former vice president Aaron Burr became a suspect in an alleged conspiracy to create a rogue country west of the Appalachians, Jefferson and others called for his head, or at least his body in court, and a conviction looked probable.

By 1807, Burr had almost no credibility. In the E

LECTION

of 1800, he declined to step aside and let his running mate claim the presidency. In 1804, the sitting vice president killed the first secretary of the treasury, Alexander Hamilton, in the country’s most infamous duel. By 1806, he was said to be orchestrating an invasion of Mexico, with plans of creating a vast empire astride the Mississippi. The evidence, though sparse, was enough to have Jefferson stand before Congress and conclude that Burr was guilty “beyond question.”

71

Two of Burr’s supposed accomplices were reviewed before the Supreme Court. Chief Justice John Marshall, refusing to bend to the will of sensationalist newspapers, found insufficient proof to accuse them of treason; he let them go. Marshall then rode to the circuit court in Virginia to try Aaron Burr in person. A furious Jefferson determined that if Marshall set Burr free, then the chief justice would have to be impeached.

72

All but demanding a conviction, the president suddenly turned somber when his own name was subpoenaed. Twice Marshall demanded he testify, and twice Jefferson refused, claiming he could not possibly attend a trial, lest “such calls would leave the nation without an executive branch.” Claiming executive privilege, Jefferson also refused to relinquish records in his possession that were pertinent to the case. “Some of these proceedings,” the president said of the documents, “should remain known to their executive functionary only.”

73

In the end, Jefferson angrily relented and sent the requested material. None of the papers, no witnesses, nothing convinced Marshall that the government had a valid argument against the defendant. Burr walked. Jefferson half expected the decision. Yet the disappointment of one more Marshall victory led the president to lament what he called “the original error of having a judiciary independent of the nation.”

74

In 1836, Aaron Burr was somewhat amused to hear that a band of Americans had started a war with Mexico to form an independent country. He found it ironic that Jim Bowie, Davy Crockett, and Sam Houston were declared heroes, while he was tried for treason for allegedly trying to do the same thing.

3

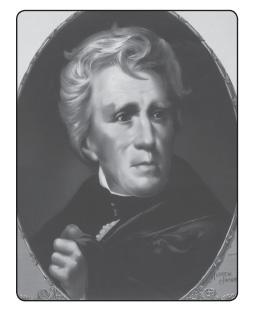

. JACKSON IGNORES THE COURT

WORCESTER v. GEORGIA (1832)

By the early 1800s, the white population in the United States was doubling every twenty years. Most Native Americans were less than enthused about the trend. Their misery worsened when Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act of 1830, requiring “voluntary” relocation to unsettled lands west of the Mississippi. But the Cherokee of Georgia had reason to believe they had won a stay of extradition.

In 1832, the state of Georgia arrested several white missionaries living with the Cherokee. Two of them, Samuel Worcester and Elizur Butler, sued the state for violating the sovereignty of their hosts. Surprisingly, the Supreme Court sided with the Native Americans and their guests, ruling that only the federal government, not the states, had authority over Native American affairs. In the majority opinion, an ailing John Marshall labeled Georgia’s actions against the Cherokee “repugnant to the Constitution, laws, and treaties of the United States.”

75

Tribal members reportedly danced after hearing the decision. One member proclaimed the verdict proved “for ever as to who is right and who is wrong.” In contrast, Governor Wilson Lumpkin swore to his legislature that he would defy the ruling “with the spirit of determined resistance.”

76

Andrew Jackson felt no need to assist the Supreme Court in forcing the state of Georgia to observe its rulings—especially when it came to Native American affairs.

Legend has it that President Jackson, the famed Indian fighter, responded by saying, “John Marshall has made his decision. Now let him enforce it.” In reality, Jackson chose to ignore the ruling, and he hinted that the state of Georgia should do the same. “It [the Supreme Court] cannot coerce Georgia to yield to its mandate,” said Jackson. “It is better for them [the Cherokees] to treat and move.”

77

Governor Lumpkin did ignore the ruling, and the Cherokee were soon forced from their land. John Marshall saw the defeat as the death knell of the Court’s credibility and possibly the end of the government upon which it rested. Lamenting the seemingly limitless power of the Jackson administration, the chief justice bemoaned, “I yield slowly and reluctantly to the conviction that our Constitution cannot last.”

78

In 1838, the U.S. government began to forcibly relocate more than seventeen thousand Cherokee from their homes in Georgia and Alabama to the Oklahoma Territory. Approximately four thousand died on the ensuing Trail of Tears.

4

. LINCOLN, TANEY, AND HABEAS CORPUS

EX PARTE MERRYMAN (1861)

Eleven states seceded. By all accounts, Maryland looked to be next. Ninety-seven percent of the Old Line State had voted against Lincoln in 1860. When Fort Sumter fell, residents lofted Rebel flags in celebration. Days later, citizens of Baltimore attacked the Sixth Massachusetts Regiment as it entered the city, resulting in the deaths of four soldiers and twelve civilians.

79

In desperation, Lincoln ordered Winfield Scott, commanding general of the army: “If at any point…you find resistance which renders it necessary to suspend the writ of Habeas Corpus for the public safety, you, personally or through the officer in command…are authorized to suspend that writ.” Neither Lincoln nor Scott had such authority. Only Congress could grant a suspension, and the legislators were not in session.

80

The right of citizens to petition against imprisonment has been a mainstay of free societies. Without it, governments can arrest without warrant, hold without charge, and imprison without trial. Certainly Lincoln was uneasy about his decision, but he rationalized his action. “I felt that measures, otherwise unconstitutional, might become lawful, by becoming indispensable to the preservation of the constitution,” an act he equated to removing an arm to save a body.

81

The arrests proceeded. In Baltimore alone, the Union army jailed news editors, a court judge, and the chief of police. Members of Maryland’s legislature were taken prisoner, along with several private citizens.

82

One of the first to protest was John Merryman, a Baltimore resident suspected of being an officer of Rebel militia. Taken from his home at 2:00 a.m. on May 25, 1861, he was thrown into Fort McHenry and held without charge. Appealing to a local circuit court, he filed for a writ of habeas corpus and won. The presiding judge happened to be eighty-four-year-old Roger B. Taney, slave owner, Marylander, and chief justice of the Supreme Court.

83

In his verdict, Taney tersely stated, “The President has exercised a power which he does not possess under the Constitution.” He sent his ruling to the commander of Fort McHenry and to Lincoln himself. Both men ignored it.

84

Many Unionists fully supported the administration. “Of all the tyrannies that afflict mankind,” claimed the

New York Tribune

, “that of the judiciary is the most insidious, the most intolerable, the most dangerous.” The

New York Times

wrote that Justice Taney “uses the powers of his office to serve the cause of traitors.” Attorney General Edward Bates worried that the Supreme Court would challenge every arrest and “do more to paralyze the executive…than the worst defeat our armies have yet sustained.” Taney began to fear he would soon be arrested, and in fact Lincoln considered doing so.

85

Nearly two years passed before Congress granted Lincoln the power to suspend the writ. The right was deemed retroactive to the beginning of the rebellion and permitted to remain until the end of hostilities, whenever that would be. Yet Taney’s decision would ultimately prevail. In the related case of

Ex parte Milligan

, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that neither Congress nor Lincoln had the right to suspend the writ of habeas corpus in Maryland because it was not a state in rebellion. But the verdict came in 1866, when the war was over and both Lincoln and Taney were dead.

Five of the justices in the 1866 case of

Ex parte Milligan

were Lincoln appointees, including the former secretary of the treasury, Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase.

5

. COURT-PACKING FDR (1937)

Twelve times the heavily Republican Supreme Court ruled his New Deal initiatives unconstitutional, including his debt relief to farmers and the creation of a minimum wage. In response, Franklin Roosevelt accused the Court of denying the needs of the country. The justices answered by refusing to attend FDR’s 1937 State of the Union Address.

86

The president had seen enough. Weeks later, in a nationwide radio broadcast, FDR called the Court a “super-legislature…reading into the Constitution words and implications which are not there.” He mentioned that forty-five of the forty-eight states had term limits for judges, and perhaps it was time to do likewise with the High Court.

87

Roosevelt offered something akin to forced retirement. “What is my proposal? It is simply this: whenever a judge or justice of any federal court has reached the age of seventy and does not avail himself of the opportunity to retire on a pension, a new member shall be appointed by the president then in office.” He also wanted the maximum number of justices to be increased to fifteen.

88