History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (58 page)

Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

Nixon’s national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, dominated foreign affairs to the point that the State Department became a big player in the administration.

JFK brought it firmly under his wing, literally. After the Bay of Pigs fiasco, he moved the meetings to the newly constructed

SITUATION ROOM

in the basement of the West Wing and elevated the power of his national security adviser. McGeorge Bundy operated what many called the “Little State Department,” often forming policy with minimal input from the Joint Chiefs or the CIA. Suspicious that even this truncated group was causing leaks, LBJ reduced the working council still further to his “Tuesday lunch” group of Bundy, Secretary of State Dean Rusk, and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara.

By the Nixon administration, policy decisions were dictated almost exclusively by the president and National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger. Carter followed Nixon’s lead with NSA Zbigniew Brzezinski. During the Reagan administration, even the president was out of the picture, resulting in a near total loss of oversight and the debacle of the I

RAN

-C

ONTRA

A

FFAIR

.

The position recovered its dignity and prestige during the tenure of George H. W. Bush with the return of Ford’s NSA Brent Scowcroft. Like Bush, Scowcroft had professional experience in the intelligence field and the armed forces, and he became one of the chief architects in the multinational victory of the First Gulf War.

77

Colin Powell had the distinction of serving on the National Security Council in three different capacities—as national security adviser under Ronald Reagan, as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff under George H. W. Bush, and as secretary of state under George W. Bush.

5

. DIRECTOR OF THE OFFICE OF MANAGEMENT AND BUDGET

Normally, Congress surrenders its obligations to the executive in small steps. One giant leap came in 1921. Before then, the House Ways and Means Committee and the Senate Finance Committee dictated what the government was going to spend in any given year. From the executive branch, individual departments and agencies would come with hat in hand, requesting a portion of available funds. The president had minimal influence on the process, except in wartime.

It was during the Great War that Capitol Hill felt it could no longer control its own spending. Under the advice of Warren Harding’s treasury secretary Andrew Mellon, Congress passed the Budget and Accounting Act, essentially putting the presidency in charge of figuring the cost of running the country. For a while the system seemed to work. Under the executive Bureau of the Budget, the debt fell from twenty-six billion dollars to sixteen billion dollars in less than a decade.

78

The unforeseen trauma of the Great Depression quadrupled the debt, but the Budget Office remained small. Even in 1939, when it officially transferred from the Treasury Department to the Executive Office of the President, the organization had a modest staff of forty-five. The monumental money pit of the Second World War boosted its payroll to five hundred employees.

79

Since then, the count has stayed roughly the same, only the name and strategy have changed. In 1970, the bureau became the Office of Management and Budget, and instead of reducing costs, the political incentive has been to procure more revenues for popular programs. Charged with defending the president’s fiscal agenda, the OMB has the power to shift discretionary funds from one area of the government to another, determine allowances for federal agencies, and make recommendations to the president as to which programs and agencies should receive the most funding.

An odd reversal of fortune, so to speak, since the submissive executive branch used to approach Congress for money. Today, every autumn, the legislature, the judiciaries, the executive agencies, and the cabinet departments humbly submit their budget requests to the OMB.

Directors of the OMB have gone on to become secretary of state (George Schultz), secretary of defense (Leon Panetta and Caspar Weinberger), and chief of staff (Leon Panetta and Josh Bolton).

6

. THE PRESS SECRETARY

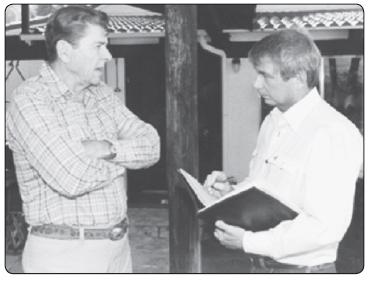

“The White House spokesman is the second most visible person in the country,” said Reagan’s press contact Larry Speakes, “which can be not only an honor but a headache.” Rarely involved in decision making, but almost always the earliest to know, the press secretary is the link between the president and the national news.

80

Acknowledging the power of the papers, Theodore Roosevelt was the first to truly cater to them, building a pressroom in the newly built West Wing. TR was also his own media front man. Presidents to follow were not so gregarious. Herbert Hoover was less inclined to speak to the press than Silent Cal Coolidge, so he hired an assistant to do it for him. FDR, conscious of the emerging influence of radio, created an entire group to work with journalists, and the White House Press Office was born.

81

As the age of information manifested itself through live television, the office became even more active and visible. Handling breaking news, plus giving briefings twice a day, the spokesperson is the first to present the official White House line on any given subject and the lightning rod for questions from the press corps. Marlin Fitzwater said it was like serving two masters, the White House and the media.

82

Ronald Reagan’s press secretary Larry Speakes (right) called the press job an honor and a headache. Speakes was one of three press secretaries to serve under Reagan during the president’s eight years in office.

Reagan Library

At times, they are instructed to lie. To explain Kennedy’s sudden cancellation of a trip to Seattle, Pierre Salinger told the media that JFK had a respiratory infection and had to return to Washington. In reality, Kennedy was rushing back to deal with the escalating C

UBAN

M

ISSILE

C

RISIS

. Jimmy Carter’s spokesman Jody Powell knew about the impending (and doomed) military rescue operation for the Iranian hostages. But when reporters inquired about a possible rescue mission, Powell maintained secrecy by denying that any rescue plan existed.

83

Constant pressure to perform well, even when the administration does not, can create a high rate of attrition. Nixon’s Ron Ziegler, the youngest press secretary to date at age twenty-nine, toughed it out the whole way. In contrast, George W. Bush was on his third press secretary in his final years. Lyndon Johnson had four. Truman went through them like a plate of pork ribs, using five.

Chief executives initially hired journalists to fill the position. Recently the tendency is to select political insiders with speaking experience. Bill Clinton made the freshman mistake of choosing neither. Opting for novelty over know-how, he paid the price in bad press. At thirty-one, Dee Dee Myers was one of the youngest and the first female to hold the job. But she had virtually no media background and minimal access to the president. Amiable but underinformed, she adapted and held on for two years. Barack Obama employed an insider as well as a journalist. His first press secretary, Robert Gibbs, had been an assistant to a series of representatives and senators, including Senator Obama. Jay Carney, his second, had worked at

Time

magazine for nearly twenty years.

84

The Class of 1901 at Independence (MO) High School included Harry S. Truman, Elizabeth V. Wallace, and Charles Griffith Ross. The country would get to know all three as Mr. President, the first lady, and Mr. Press Secretary, respectively.

7

. DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS

Selling the presidency, the Office of Communications is the public relations firm of the White House. Clinton’s first director, George Stephanopoulos, exaggerated only a little when he said, “By definition, if the President isn’t doing well, it’s a communications problem.”

85

From the beginning, administrations knew the vital importance of presenting their worldview to the masses. Initially, it was done covertly through partisan newspapers. Later on, presidencies became more aggressive in disseminating their brand of information, especially in wartime. During U.S. involvement in the First World War, the Wilson administration hired “Four-Minute Men,” public speakers who gave prepared short speeches at movie houses before the main feature. During World War II, FDR’s Office of War Information delivered newsreel footage.

86

The office truly came into its own under Nixon, who separated its duties from the Press Office. Disseminating favorable information through television, radio, periodicals, photography, and speechwriting, checking the nation’s pulse through polls, research, news analysis, and public liaisons, his administration was able to sidestep the press and appeal directly to the “great silent majority.” For Dick, it worked wonders, especially in damage control. Despite Cambodia, Kent State, Laos, Vietnam, W

ATERGATE

, and a slowing economy, he won reelection by a landslide in 1972.

In contrast, Ford, Carter, and George H. W. Bush reduced staff, wrote and edited most of their own speeches, depended on personal appearances to reach the people, and let their work ethic do most of the talking. In the age of high-dollar marketing and high-speed media, their methods proved slow and unresponsive. In turn, Reagan offered a lesson in how it should have been done. His communications staff released thousands of warm, colorful, patriotic photos of the president every month. They carefully edited video pieces to show the septuagenarian hard at play at his California ranch. They perfected the sound bite, stayed in tune with his ratings, and kept him away from the press.

87

Generally, Republican administrations also tend to perform better than their opposition in presenting a united front. As Dick Cheney insisted, “You’re there to run an effective presidency. And to do that, you have to be disciplined in what you convey to the country.” Through internal briefings, media handlers, and carefully prepared responses to difficult questions, they often appear in lockstep, presenting a greater appearance of control, all of which falls under the jurisdiction of the Office of Communications. It is a high-stress job, and most directors last an average of eighteen months before they step down or are replaced.

88

Bill Clinton’s Office of Communications was the first to set up an official White House website.

8

. DIRECTOR OF LEGISLATIVE AFFAIRS

Presidents can appeal directly to the public for moral support on an issue, but they communicate their official position through the director of legislative affairs. Proposing bills in the House, getting treaties passed in the Senate, mending fences after vetoes, and getting appointees approved all takes live bodies from the Executive Office working directly on Capitol Hill.

Familiar with the dangers of poor communication between allies, Eisenhower established the first legislative liaison office. Small, informal, and bipartisan, it was effective enough for his administration’s modest agenda. Kennedy and Johnson were more aggressive in their efforts, and their directors emphasized party loyalty to sway voters. Carter reduced his liaison staff, and he famously struggled for his first two years, mystified that party members were not more obedient. Publicly, Reagan could be downright abusive toward the Hill, but his liaison office was one of the most organized and cooperative, using generous bargaining to win over lawmakers. The tactic often backfired, however. Reagan’s budget director David Stockman remembered the irony of convincing legislators to back the 1981 tax cut bill by enticing them with huge tax breaks for corporations, real estate developers, and oil companies in their districts.

89