History of the Second World War (104 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

The much criticised ‘diversion’ was beneficial to Bomber Command, as it not only eased the strain on it but was a stimulus to the improvement of bombing. Moreover German fighter opposition over France was much less than in the ‘Battle of Berlin’ and other attacks on targets in Germany.

The precision of bombing was helped by the innovation in technique developed by Wing Commander Leonard Cheshire in low-level marking of targets by Mosquitoes. First applied in France during April, target after target was destroyed without many bombs overshooting the target and killing French civilians as Churchill had feared. The average bomb error was reduced from 680 yards in March to 285 yards in May.

The success of the ‘communication’ attacks before D-Day strengthened Tedder’s view that such a campaign should be extended to Germany, with top priority. He felt that a collapse of the German rail system, besides disrupting troop movement — and thus being welcome to the Russians — would also mean the collapse of her economy. It would thus be an alternative to Harris’s general area-bombing and to Spaatz’s oil campaign. It certainly had a quicker effect on the German Army and on the Luftwaffe than general area-bombing.

The period after the cross-Channel invasion saw the bombers attacking a variety of targets. While the Americans turned mainly to oil and aircraft targets during these months, only 32,000 of the 181,000 tons of bombs dropped by Bomber Command during the period were on targets in Germany.

The trend away from area-bombing became very marked. The British Air Staff embraced the American view that oil targets should be given priority. Already in April the 15th U.S.A.A.F. had reached out from Italy and attacked the Ploesti oilfields in Rumania. On May 12, the 8th U.S.A.A.F. from England started attacking oil targets in Germany. Although 400 German fighters came up to oppose the 935 American bombers, they were beaten off by a thousand American fighters, and lost sixty-five of their number, against an American loss of forty-six bombers.

This campaign became greater after D-Day, and in June the Air Staff, conscious of Bomber Command’s developments in precision-bombing by night, ordered British attacks on oil targets. The Gelsenkirchen raid on the night of July 9 was fairly successful, though rather costly, but the other raids were less effective because of the weather, while the losses were catastrophic — ninety-three bombers were lost, mainly to night-fighters, out of the 832 despatched on three nights.

The American attacks continued in full force. On June 16, over a thousand bombers escorted by nearly 800 fighters were employed, and on the 20th the bombers totalled 1,361. On the next day Berlin was attacked, while another force attacked oil plants and flew on to land in Russia. (After their cool reception there the experiment was discontinued.) American losses were heavy, but an increasing number of oil plants were disabled, with damaging effect on the Luftwaffe’s fuel supply. By September this was reduced to 10,000 tons of octane — whereas a monthly minimum of 160,000 tons was needed. By July every major oil plant in Germany had been hit, and the vast number of new aircraft and tanks produced by Speer’s efforts were becoming virtually useless for lack of fuel.

While the effective number of German aircraft fell, the Allied air forces grew stronger. Bomber Command’s first-line strength in bombers rose from 1,023 in April to 1,513 in December, and to 1,609 in April 1945. The 8th U.S.A.A.F’s strength in bombers rose from 1,049 in April 1944, to 1,826 in December, and 2,085 in April 1945.

Meanwhile Bomber Command had adopted mass day bombing for the first time. Harris’s suspiciousness about it was allayed by the lack of opposition it met from the Luftwaffe compared with what was met by night. The first large daylight raid was made against Le Havre in mid-June, and, like those that followed, was escorted by Spitfires. By the end of August Bomber Command was raiding the Ruhr in daylight, and still finding the opposition negligible.

These new circumstances tempted Bomber Command to resume night attacks on German oil plants. These attacks proved more effective and less costly than they had before. The very successful raid of August 29 on the distant target of Konigsberg, though not itself an oil target, showed the all-round improvement.

Thus was October 1944 to May 1945 the time of domination by the bombers. Bomber Command dropped more bombs in the last three months of 1944 than during the whole of 1943. The Ruhr alone was battered by over 60,000 tons of high explosives in those months. Moreover, as the Official History says, it was a time when the bombers had ‘virtual operational omnipotence’.* Under the onslaught, German power of resistance was gradually ground down, and her war economy strangled.

* Vol. III, p. 183.

In view of this new capacity for precision bombing, with little opposition, it is questionable whether it was wise, either operationally or morally, for Bomber Command to devote 53 per cent of its bombs in this period to town areas, compared with only 14 per cent to oil plants and 15 per cent to transportation targets. (The corresponding figures for January-May 1945 were 36.6 per cent, 26.2 per cent, and 15.4 per cent — a ratio that was still very questionable.) The ratio in the Americans’ targeting was essentially different. Their idea of aiming to hit Germany’s known weak points was more sensible than that of trying to ensure that every bomb hit something, and somehow weaken Germany. It also avoided the increasing moral censure that Harris’s policy was to attract.

The final phase suffered overall by a failure to maintain the best priorities. A directive of September 25, 1944, established oil as the first priority, with communications jointly heading a list of others. Here was a good chance to shorten the war, since Bomber Command was also concentrating on targets in Germany by October — dropping 51,000 tons of bombs there, and suffering losses of less than 1 per cent. Yet two-thirds of the October raids were for general area-bombing, while little was thrown on oil or communications. Thus on November 1, 1944, the commanders were given a fresh directive setting oil as the first priority, and communications as the second; there were no others to confuse the choice. The two objectives, now relatively easy of attainment, would certainly tend to hasten Germany’s collapse quicker than area-bombing.

Harris’s obstinacy, however, prevented the plan from being properly carried out — he even threatened resignation in resistance to it.

At the beginning of 1945 the outlook became complicated by the Germans’ counteroffensive in the Ardennes, the advent of their jet fighters, and Schnorkel submarines. That led to a fresh discussion of priorities. But with the various authorities pulling in different ways, the issue became a compromise — and, as with most compromises, hazy and unsatisfactory.

The most controversial aspect is the deliberate revival of ‘terrorisation’ as a prime aim. It was revived largely to please the Russians. On January 27, 1945, Harris was given instructions to carry out such blows — which thus became second in priority to oil targets, and ahead of communications and other objectives. As a consequence, the distant city of Dresden was subjected to a devastating attack in mid-February — with the deliberate intention of wreaking havoc among the civil population and refugees — striking at the city centre, not the factories or railways.

By April, worthwhile targets were so few that both area-bombing and precise strategic bombing were abandoned in favour of direct assistance to the armies.

COMPARATIVE TARGET RESULTS IN STRATEGIC BOMBING OFFENSIVE

Even when the torrential bomb-deluge after the summer of 1944 began to reduce German production, Speer’s great efforts in dispersal of plant and in improvisation did much to counter the material effects. Morale also kept up in a remarkable way, until after the Dresden attacks in February 1945.

OIL TARGET ATTACKS

Owing to the long immunity of the distant oilfields in Rumania and the increasing development of synthetic plants in Germany, Germany’s oil stocks actually reached a peak in May 1944, and only began to shrink in later months.

More than two-thirds of the hydrogenated oil was produced in seven plants, whose vulnerability was manifest, and as the refineries were also vulnerable the effects of the concentrated bomber attacks on these installations in the summer of 1944 quickly began to take effect. April’s output of automotive fuels was reduced to half by June, and to a quarter by September. Aircraft fuel production fell to the 10,000 tons of September against a target figure of only 30,000 tons — whereas the Luftwaffe’s monthly minimum demand was 160,000 tons. About 90 per cent of the aviation fuel, the most vital need of all, came from the Bergius hydrogenation plants.

As German consumption was increased in meeting ‘Overlord’ and the Russian advance from the East, the situation became very serious — from May onwards consumption exceeded production. Speer’s frantic countermeasures succeeded in achieving some alleviation, and produced a rise in fuel stocks prior to the Ardennes counteroffensive in mid-December, but not enough to maintain it effectively, and that too prolonged battle went far to exhaust the stocks, in combination with the Allied oil attacks in December and January. Bomber Command’s night attacks were particularly effective, owing to the much larger bombs that the Lancasters could now carry, and their new standards of accuracy in night-bombing.

The attacks on oil targets also greatly cut down German production of explosives and synthetic rubber, while the shortage of aviation fuel led to almost the entire cessation of training, and drastic reduction of combat flying in the Luftwaffe. For example, only fifty night-fighters at a time could be employed at the end of 1944. Those deficiencies, too, went far to offset the potential value, and menace, of the new jet-engined fighters which were now being introduced in the Luftwaffe.

COMMUNICATION TARGET ATTACKS

This objective, a mixture of tactical and strategic, was clearly of tremendous importance in the success of the Normandy invasion and the battle there, but its effect is more difficult to assess as the Allied armies approached the Rhine. The November plan focused on railways and canals in Western Germany, and particularly around the Ruhr — as cutting off coal supplies would bring the main part of German industry to a halt. The effects were very damaging, and much worried Speer in the autumn of 1944, but the Allied chiefs tended to underrate them in their own assessments. Divergence of views delayed and diminished this course of action, and its effects. But in February 1945 a total of some 8,000-9,000 aircraft were busy in attacking Germany’s transport system. By March it was in ruins and industry starved of fuel. After the loss of Upper Silesia in February, when the Russian advance captured that area, Germany had no alternative source of coal supply. Her steel production, although she still had sufficient iron ore, was not enough to meet her minimum ammunition requirements. It was then that Speer, realising that the position was hopeless, began planning for the period after the war.

DIRECT ATTACKS

The results of such attacks now became more and more apparent. City after city was devastated. German industrial production steadily shrank after its peak month, July 1944. The Krupp works at Essen ceased production after October. It was often the destruction of electricity, gas, or water systems that primarily caused the losses in production. Outside the Ruhr, however, the sheer shortage of raw materials, resulting from the breakdown of the transport system, was the main factor in the final collapse of German industry, in 1945.

CONCLUSIONS

The strategic bombing offensive against Germany opened with much hope, but at the outset had very little effect — showing a vast excess of confidence over common-sense. The gradual development of a sense of reality was manifested in the abrupt change from daylight to night bombing, and then in the adoption of the policy of area-bombing — questionable as this was in many respects.

Until 1942 the bombing was merely an inconvenience to Germany, not a danger. It may have given a fillip to the British people’s morale, although even this is questionable.

In 1943, thanks to ever-growing American help, the damage inflicted by the bomber forces of the two Allied countries became larger — but had, in fact, no great effect on German production, or on the German people’s morale.

A real and decisive change did not come until the spring of 1944, and that was due mainly to the Americans’ introduction of adequate long-range fighters to escort bombers.

After rendering great service to ‘Overlord’, the Allied bombers returned to their attack on German industry with much increased success. In the last nine months of the war they owed much to their new developments in navigation and bombing techniques, as well as to shrinking opposition in the air.

Through indecision, and divergence of views, Allied progress in the air, as on the ground, suffered from lack of concentration. The potential of the Allied air forces was greater than their achievement. In particular, the British pursued area-bombing long after they had any reason, or excuse, for such indiscriminate action.

There is ample evidence to show that the war could have been shortened, several months at least, by better concentration on oil and communications targets. Even so, despite the errors in strategy and disregard for basic morality, the bombing campaign unquestionably played a vital part in the defeat of Hitler’s Germany.

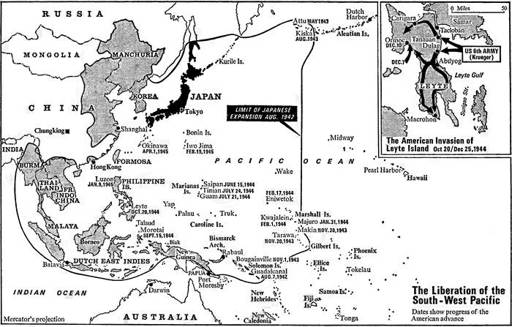

CHAPTER 34 - THE LIBERATION OF THE SOUTH-WEST PACIFIC AND BURMA