Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing (18 page)

Read Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing Online

Authors: Melissa Mohr

Tags: #History, #Social History, #Language Arts & Disciplines, #Linguistics, #General

Unless you were dealing with someone as forthright as Margery Baxter, these issues were abstruse and confusing, even in the fifteenth century. If somebody told you that “

the sacrament on the

altar is very God’s body in form of bread, but it is in another manner God’s body than it is in heaven,” as one Lollard stated his position on the Eucharist, would you call him a heretic and burn him, or not? Rather than wade around in the murky waters of accidents versus substance, orthodox authorities preferred a simpler test for heresy: they would ask suspected Lollards to swear on a Bible. If the person swore, okay; if not, pile up the faggots.

When threatened with punishment or death, some Lollards agreed to swear on the Bible, as did John Skylly, who in 1428 recanted his beliefs and asserted that “

I abjure and forswear

, and swear by these holy gospels by me bodily touched that from henceforth I shall never hold error.” The authorities didn’t want to give him any wiggle room—he had to swear his oath exactly as the orthodox Catholic authorities specified, “bodily touching” the Bible. In the same situation, many other Lollards refused to swear and were sentenced to death. Mostly they were burned at the stake, like William White, Hugh Pye, and John Waddon in 1428; occasionally the executions were more imaginative, as was the case with John Badby, who in 1410 was burned to death in a barrel.

The bizarre thing about using swearing as a litmus test is that, generally, Lollards had nothing against it. Lollards and orthodox Catholics both agreed that it was proper to swear, that Christ did not forbid all oaths. They agreed that oaths should not be made vainly or rashly, but according to the rules that God laid down in Jeremiah. And they agreed that

you shouldn’t swear by creatures

, created things that reflect God’s glory but are not part of him, exemplified by the list Jesus gives in the Sermon on the Mount—not by heaven, not by the earth, not by Jerusalem, not by your own head.

Where they disagreed was on whether the Bible should be considered a “creature.” The orthodox Catholics thought that the Bible should be considered a part of God, since it is his Word. The Lollards argued that the Bible was a physical book made by human hands, hence earthly and forbidden to use in oaths. If the orthodox authorities had asked them to swear by God, or by God’s holiness, or

by God’s great name, they would have, but they would not do it with their hand on the Bible, touching, as they believed, a creature.

William Thorpe, for example, was all ready

to swear at his trial in 1407—“Sir, since I may not now be otherwise believed, but by swearing … therefore I am ready, by the word of God (as the Lord commanded me by his word) to swear.” But when his examiners brought out a Bible and told him to “lay then thine hand upon the book, touching the holy gospel of God,” suddenly he wouldn’t do it. The fate of the steadfast William Thorpe is obscure, but he was probably imprisoned for life. Orthodox authorities imprisoned or executed hundreds of people for a disagreement, in part, over an interpretation of an interpretation of Matthew 5:34–37.

Given that swearing had so central a role in medieval English society, it is no wonder that “

false swearing becomes one of the most commonly

(and vehemently) denounced sins of medieval times,” as philologist Geoffrey Hill notes. Even if an oath is false or is sworn for sinful reasons, God looks down from heaven to witness it. He guarantees oaths that seduce young girls into ruin, that trick people out of their lawful inheritance, that basely deny responsibility for a murder. Because of the bargain he made with humanity in the Bible, God has in essence no choice but to witness these oaths that are repugnant to him. God can punish these swearers, though, and he was often thought to do so—the pastoral literature abounds with stories about false swearers who incur his wrath.

In one example from 1303

, a rich man and a poor man are fighting about a piece of land. The rich man declares his intent to swear that the land is his, though it actually belongs to the poor man, and he is able to find many compurgators who are themselves willing to swear that his oath will be good. It looks as if the rich man will triumph, but “when he had sworn his oath / And kissed the Book [the Bible] before them all / He never rose up again / But lay dead before them there.” God knows that the rich man has forsworn himself, and strikes him dead. “See how vengeance was his reward,” the story concludes, “Almighty God, who is Truth, / He would take to false witness.”

Sometimes, inscrutably, God doesn’t punish such swearers. False swearing then damages God’s honor and reputation, denigrating the Holy Name that language should instead praise and glorify.

Or, as Steven Pinker writes

, “every time someone reneges on an oath and is not punished by the big guy upstairs, it casts doubt on his existence, his potency, or at the very least how carefully he’s paying attention.” We saw in the previous chapter how Yahweh’s rise to the top of the celestial hierarchy was linked inextricably to his reputation vis-à-vis the other gods. Swearing by Yahweh confessed him to be omniscient and omnipotent—the only God you need. False swearing dares him to prove this, again and again. The more people swear falsely and escape punishment, the less reliable God’s power comes to seem.

Vain swearing—swearing habitually and/or for trifles—was seen to be another problem in medieval England, for similar reasons. God had to fulfill his side of the bargain and judge the righteousness of an oath anytime someone mouthed the proper formula, whether in a matter of life or death or to express annoyance while playing cards. Reading Chaucer, or indeed almost any piece of medieval literature, it is obvious that vain swearing was widely practiced. Chaucer’s characters can barely start a sentence without prefacing it with “By God’s soul,” “For Christ’s passion,” or “By God’s precious heart.”

The Pardoner addresses this kind of language

before he starts his tale, warning that God will take vengeance on these swearers: “Frequent swearing is an abominable thing.” He notes that vain swearing is so important to God that he forbids it in the second commandment, before he outlaws “homicide, or many other cursed things” in later commandments.

One kind of vain swearing worried medieval commentators more than all the rest—swearing by the parts of God’s body. Chaucer’s Pardoner gives examples of these oaths as he rails against improper swearing: “by the blood of Christ,” “by God’s arms,” “by God’s nails,” and similar phrases. In tract after tract, writers single out these oaths for prohibition, repeating with the anonymous author of “On the Twenty-Five Articles” (c. 1388) that “

it is not

lawful to swear by creatures, nor by God’s bones, sides, nails, nor arms, or by any member of Christ’s body, as most men do, for this is against holy writ, holy doctors, and common law, and great punishment is set on it.”

Jacob’s Well

discusses these oaths

as the fifth leaf on the branch of forswearing (which is the sixth branch on the tree of evil tongue, which grows somewhere in the ooze of gluttony), and explains why they are so very dangerous. People who use such oaths “rend God limb from limb, and are worse than Jews, for they rent him only once, and such swearers rend him every day anew. And the Jews didn’t break his bones, but they break his bones, and each limb from the other, and leave none whole.” The problem with the body-part oaths is that they “rend” God—they tear his body apart. In Catholic doctrine, Christ ascended to heaven in his physical, human body and now sits at the right hand of God, waiting to come again in glory to judge the quick and the dead. (One Lollard has somehow acquired the information that Christ’s body “in heaven … is seven foot in form and figure of flesh and blood”—

Christ is seven feet tall

.) This is the divine body that is under threat from oaths. When you swear “by God’s nails,” you tear the nails out of Christ’s hand as he sits in heaven.

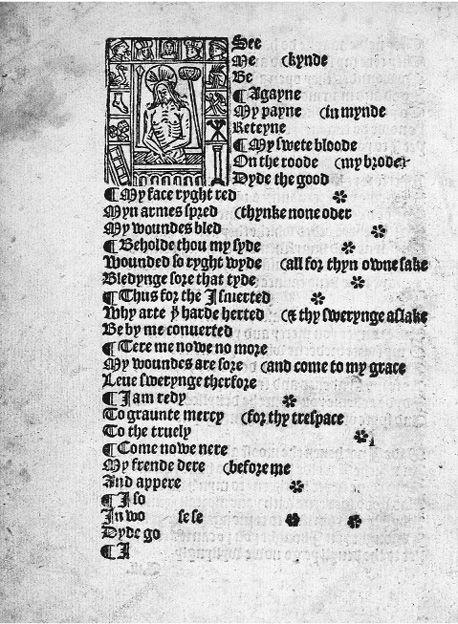

The first pattern poem written in English

depicts the result of such swearing. Pattern poems, in which the lines are laid out on the page to form a specific shape, were more usually made to look like eggs, wings, altars, or crosses. In Stephen Hawes’s 1509

The Conversion of Swearers

, though, the lines scattered across the page suggest Christ’s bones, and printer’s ornaments resemble flowers strewn over a corpse. “See me / Be kind,” Christ pleads. “Tear me no more / My wounds are sore / Leave swearing therefore.” (See next page.)

How could God’s creatures wield such power over their Creator? Yet it is the same power that people exercise in the ceremony of the Eucharist. Swearing by God’s body parts is in fact a perverse version of this sacrament. In the Eucharist, a priest speaks a “working word” to create God’s body, then breaks it with his hands; in swearing, all who utter the requisite formulae can break God’s body with their words alone.

The first page of the pattern poem from

The Conversion of Swearers

, 1509.

To Catholics, the Eucharist is the sacrament in which God’s physical body is shown to or eaten by his people, effecting and signaling their salvation. Though worshippers appear to consume bread, they are actually eating God’s physical body—the same body born of Mary, crucified on the cross, and now sitting in heaven—transubstantiated into a wafer.

An Easter Sunday sermon

from the late fourteenth century explains what the Host consists of and how it is the sole instrument of salvific grace: “And the same body that died on the Cross and this day rose truly God and man, the same body is on the Sacrament on the altar in form of bread … And whosoever eats it, he shall live forever.”

The mechanism of this miracle

is based on Aristotelian theories of matter, as we saw with the Lollards. The wafer can look like bread but be Christ’s body because after consecration the “accidents” of bread, its whiteness and roundness, remain, but its “substance” or “subject” has been changed or annihilated and replaced with the body of Christ. The priest performs this miracle by pronouncing the words of the sacring during Mass: “Hoc est enim corpus meum,” “This is my body.” These words literally transform the bread on the altar into Christ’s body, the Real Presence.

There are many exempla from the medieval period that explain in bloody detail exactly what is going on during the Eucharist.

Handlyng Synne

tells

the tale of a monk who doubts

the real, physical presence of Christ in the Host since he cannot see it with his bodily eyes. It looks like bread—how could it be God’s body? He and two abbots pray to God to “to show the truth / that you are the sacrament of the Mass” and are “rewarded” with a behind-the-scenes look at what really goes on when the priest speaks the magic words. After the words of consecration, a living child appears on the altar. The priest kills the child and divides him up, offering the monk a piece of bleeding human flesh instead of the wafer. The monk “thought that the priest brought on the paten / Morsels of the child newly slain, / And offered him a morsel of the flesh, / With all the blood on it, still fresh.” The sacrifice of the Mass is quite literally a sacrifice. This

exemplum also makes clear why Christ’s body must be concealed in the “accidents” of bread, “for if we took it as flesh, we would be sick and disgusted and forsake it.”

These miracle-of-the-Host stories resemble the complaints against swearers that also abound in the pastoral literature. These complaints demonstrate in equally graphic terms what swearing does to the body of God. The

Gesta Romanorum

, an early fourteenth-century monastic collection of moral fables, contains a representative tale about the consequences of vain swearing.

There was once a man who swore constantly

, the tale goes, his whole life long. He left no part of Christ’s body untouched with his terrible oaths. His friends warned him that he should stop, but he would not, no matter what anyone said to him. One day, the most beautiful woman he had ever seen visited him. She was Mary, Christ’s mother, and she came to show the man her son. “Here is my son,” she told him, “lying in my lap, with his head all broken, and his eyes drawn out of his body and laid on his breast, his arms broken in two, his legs and feet also. With your great oaths you have torn him thus.” Just this scene is depicted in a circa 1400 wall painting from St. Lawrence’s Church, Broughton. Here, fashionable gentlemen hold parts of Christ’s body, which they have ripped from him with their oaths. Christ himself lies partially dismembered in his mother’s lap—note his right arm and leg, with the bones sticking out. Just as miracle-of-the-Host stories are supposed to show what really happens when the priest pronounces his “working word,” these complaints against swearers show what really happens when people swear.

In these two kinds of exempla, God reveals to our physical senses truths that we must ordinarily apprehend through faith. They echo the story of Doubting Thomas, who “will not believe” Christ’s resurrection until he “shall see in his hands the print of the nails, and put my finger into the print of the nails, and thrust my hand into his side” (John 20:25). Jesus makes allowances for Thomas’s human frailty and exposes his body to the disciple’s touch, his body proving his resurrection. Thomas deems this physical sight and touch to be satisfactory evidence, and he finally believes his God is risen.