Imperial (160 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

Imperial is Joe Maruca, Chairman, who says: At ten-fifteen we will take in closed session the item of the Sierra Club versus the EPA.

He explains: We’re expecting a phone call from an attorney who is representing us in this EPA matter.

The Sierra Club wants to shut down the whole valley, and we can all go to San Diego, he says bitterly. With our

water.

This is Imperial; this is Joe Maruca, Chairman.

I support the Sierra Club, and that’s irrelevant. I disagree with Stella Mendoza about the Salton Sea, and that’s irrelevant, too. (By the way, Gale Norton, the Interior Secretary, has been quoted as saying that

the Bush administration does not see preserving the inland lake as a funding priority.

)

Imperial is Joe Maruca. Imperial is Stella Mendoza. Imperial is Leonard Knight, who lays another coat of paint on Salvation Mountain and says:

When I get too close to people, they always want me to do it their way. And then it looks like I want to do it my way. And most of the times, their way is right. But I still like to do it my way.

Imperial has now been surrounded, like an old Victorian in Riverside with gables and round windows which resemble compass dials, an old house ringed round with freeways.

Imperial is what she is, outspokenly. What about Imperial’s enemies? The Department of the Interior’s e-mails to the Metropolitan Water District

suggest that the federal government may have worked behind the scenes . . . to develop a Colorado River-sharing pact that favors the giant Los Angeles-based wholesaler.

The Imperial Irrigation District bitterly declares for the record that Interior’s Regional Director, Mr. Robert Johnson, secretly met with MWD in 2002 to formulate a “gameplan” against them.

Mr. Johnson formed his opinions long ago.

Meanwhile, Ruth Thayer, a subordinate of Mr. Johnson’s, e-mails another Interior employee named Jayne Harkins. Poor Ruth wants to know what she should do. Having revised her notes, she feels ready to push the SEND button, but she’s been cautioned that electronic communications are potentially public documents, in which case

IID will be able to get them.

Wouldn’t that be awkward in this aboveboard, impartial public review process? We need have no fear that our lands will not become better and better as the years go by.

Another e-mail suggested that Metropolitan and Interior officials discussed “how to bulletproof” a federal order to take some of Imperial’s water.

Tamerlane’s warriors come galloping into the square.

IMPERIAL REPRISE

Standing today by the grave of that infant civilization which blossomed, amidst such hardships, upon a desert, we would fain lift the veil and see the unthought-of transformation which fifty years will bring.

Tuesday, December 10, 2002: EL CENTRO—In a stunning move that could lead to a statewide water crisis, Imperial Valley officials Monday rejected a controversial proposal to reduce their water use and sell the excess to San Diego . . . “We want to transfer water, but we want to do it on our terms,” said board President Stella Mendoza, who voted against the sale.

Tamerlane’s warriors gallop into the square.

EPITAPHS FOR A DONE DEAL

So on that day in 2002 they began with the Pledge of Allegiance. The auditorium was mostly full. An anxious man asked: Madam Chairman, is this the time to discuss the water transfer?

Not yet, said Stella Mendoza.

Finally a Mr. Carter began to speak. He was one of the Imperial Irrigation District’s lawyers.—We have negotiated an agreement, he began. Inflow into the Salton Sea will not be different than it would have been absent the program.

But after fifteen years, he said, that could be changed. San Diego will only receive half of what she wanted during that fifteen years.—Reassuringly, Mr. Carter said: IID has a right to reset our agreement in Year Six.—The socioeconomic impacts of fallowing, he said, would be

tracked, monitored and mitigated.

Stella Mendoza said: I think you all know how I stand on the water transfer. I can’t support it on a personal level.

Bruce Kuhn said: I on the other hand believe that no action could have put us in a worse situation.

Rusty Jordan from Brawley was saying: I looked up another word called

extortion . . .

And someone else said: I don’t know that it’s wise to negotiate with people that threaten, because it colors the result.

In all, five million acre-feet are going away, said a greyhaired man named Larry Porter, his voice almost trembling.

Cliff Hurley from El Centro, a whitehaired man, shakily requested to know whose farms would be fallowed.

A youngish, cleancut man named Steve Olson said: What you’re embarking on is a grave mistake. I’m telling you, you need to have some serious legal counsel. Succinctly put, once they have it for five years, they’ll have it forever.

In a trembling voice, Stella asked if this was true.

Hitching up his belt, a man named John Pierre said: Lloyd Allen asked all of us farmers to stick together. When Lloyd was there he conducted himself as a gentleman. Mr. Maldonado conducted himself as a gentleman.

A man said: I think you’ve given us the best deal we can possibly get.

DEFINITION OF A POINT SOURCE

As the Imperial Irrigation District’s lawyers later told the tale,

Interior sought to push IID into the QSA

312

by rejecting IID’s estimated water “order” for 2003 and promising IID water to junior right holders

unless

IID signed the QSA by December 31, 2002 . . . IID approved a revised QSA on December 31, 2002, and signed an agreement with SDCWA.

313

However, Interior rejected the form of the QSA approved by IID.

On December 27, 2002, Interior notified IID that Interior would not deliver IID’s

2003 water estimate of 3.1 MAFY. Interior informed CWD,

which is to say Coachella,

that it would receive its full request of 347 KAFY, even though CWD’s rights are junior in priority . . .

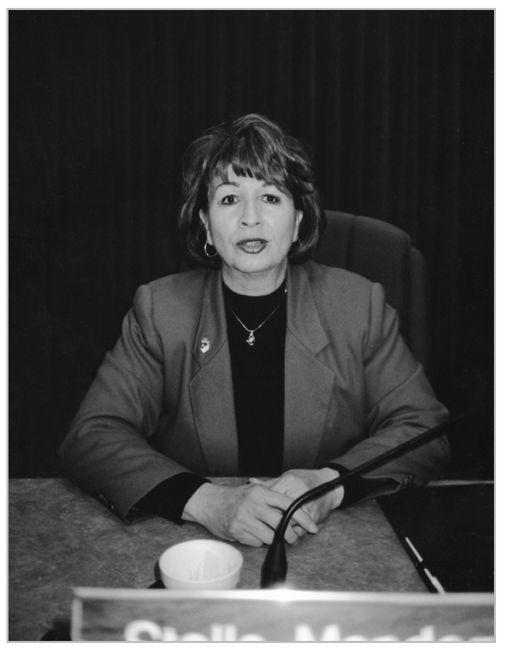

Stella Mendoza at the fateful IID meeting

(A year later, Richard Brogan said: Coachella, what I would find here, I believe their ag producing ground is decreasing. However, they’ve got more golf courses per capita there than anywhere in the country. We’re talking monumental. Rancho Mirage, Palm Desert. Are we going to create a lifestyle for certain people who thrive because of growth? You don’t have your average everyday laborer going to golf, because of hundred dollar green fees.)

Meanwhile, continued the Imperial Irrigation District’s lawyers,

Interior informed MWD that it would receive 713 KAFY of water (assuming no execution of the QSA), rather than the 550 KAFY that is allocated to MWD at priority 4.

Imperial Irrigation District lost three hundred and thirty thousand, four hundred acre-feet to which it possessed senior vested right. For Interior, it must have been as easy as killing squirrels with Cyan-o-Gas back in 1925.

It costs a dollar to feed a squirrel. It costs 2c to kill him. Let’s kill him.

On 18 March 2003, a federal district court judge ordered the government of the United States to deliver the Imperial Irrigation District’s quota of water, uncut. Judge Thomas J. Whelan cited irreparable harm to the Imperial Irrigation District and failure of the government to establish its case or respect its own procedures. But in much the same way that in the Hotel 16 de Septiembre in Mexicali the whores use any available room that’s not locked, make love rapidly on top of smelly blankets, throw the condom on the floor, remake the bed if the blankets have moved out of place, remake their iron-stiff hair, then rush back downstairs in search of new business, so the Interior Department altered a few paragraphs of its water reduction order in a flash, without mussing up the blankets, and sent it right back. (Definition: A point source is a specific site of pollutant discharge. In this case, the point source is our incorruptible Interior Department.)

On 15 March the federal district court published its decision, and in that document stated that there was a

very strong likelihood that the defendants,

namely the Interior Department,

breached the Seven Party Agreement

between the Colorado River states.

WATER’S SAVIORS

If you like, Imperial’s attitude toward Los Angeles was a mirror of Owens Valley’s in 1924:

an American community . . . driven to defense of its rights,

says the Inyo County Register. The Owens Valley was divided, needless to say, and so was the Imperial Valley.

Even as the Imperial Irrigation District struggled in court against Interior, a coalition of water farmers called the Imperial Group filed suit against the Imperial Irrigation District, accusing it, among other things, of

wasting water.

In the newspapers, the Imperial Group appeared to be most frequently associated with a man named Mike Morgan. A search of property records located twenty-six parcels, many of which were labeled, as we might expect from a water farmer,

waste land, marsh, swamp, submerged-vacant land.

You may remember that Rudy Maldonado was one of the two Board members who voted straightaway in favor of the water transfer. Mr. Ray Naud of El Centro found it

interesting,

he writes in to the paper,

that Allen and Maldonado both have supported the sale of water and fallowing since they have been on the board.

He informs us that he visited the county recorder’s office, discovering that among those who donated between five hundred and a thousand dollars to Maldonado’s campaign was a certain Mike Morgan.

Mike Morgan, said Richard Brogan slowly. He’s very aloof, very difficult to reach. A very private person. He’s someone who grew up with extra houses in Colorado, in Mexico. He probably grew up wondering, where were the folks last night? In Colorado or Mexico? He’s different.

Of Mike Morgan, Richard Brogan also said: You know where his background is in money? He’s the grandson of—and Mr. Brogan named a name.—They have that ground around the Salton Sea, he said. It’s those people with land like that who have the real strong motives. Morgan can write checks quicker than anybody else could. I don’t think he’s the richest. I don’t know for how long his family will back him in bad business deals. Morgan, his hobbies are hunting and fishing in the Gulf of Mexico. I think he owns a nice little recreational place six, seven hundred miles south on the east side . . .

Who was Mike Morgan? I never got to meet him, so I must repeat the words to you of the old pioneer from Heber:

I don’t want you to write that down. This is all just background.

“IF WE HAVE THE RIGHT TO DECIDE”

I asked Mr. Brogan for his feelings about the water transfer, and he said:

I think this water thing is very minute in the overall picture, but I don’t understand how people can’t be concerned with the lifestyle change that’s coming.

You think it is going to be a dustbowl here?

Well, forty to sixty thousand acres is a lot of jobs. The ag money spent here goes in a circle. It goes to land leasing, to taxes, and so on back to land leasing. Now it’s going to be one check from the water users to the landowners. If the landowner chooses to live in a beachfront house in Coronado . . . They’ll obviously fallow the less productive ground to start with. But then . . .

I waited, and he said: Well, I have a twofold feeling. If that’s gonna happen, then I’m still a believer in the rights of property ownership, so I don’t have a problem there. But I think we’re being

forced

into that. I think the Department of the Interior is forcing us. I believe in free enterprise,

if

we have the right to decide. A lot of these people like to grow two crops, lettuce and asparagus. High-dollar crops. If the price is up they can learn to make a million dollars with eighty acres, but they can’t do that without water. I think that the government is trying to start a precedent. Now, a lot of these people are risk takers. They’d rather try lettuce. Is water better than wheat or alfalfa? Potentially, yes. And then are there middlemen here? Is the government involved in the transaction? Is there sales tax on the water?

After awhile he shook his head and said: We have a government in Washington creating a dustbowl regardless of the human sacrifice.

“IF WE GET PAID ENOUGH”

Kay Brockman Bishop was more resigned. Perhaps she even approved of the water transfer, for she said:

I think it’s inevitable. I think we’d better learn how to make money and get more innovative. I think we’re wasting water now. I think it’s idiotic to think you can do it without fallowing something. In a downtime, you do the extra work.

If we get paid enough for that fallowing, we’ll do it fine. I don’t know anybody, and I know a lot of farmers, that’s shortened up his crew because of fallowing. If you’ve got workers working for you, you’ll keep ’em.