Imperial (161 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

I asked her whether she felt sorry for the people of Owens Valley, and she replied: They simply didn’t get what they should have gotten. They let Los Angeles buy up all that land without thinking what was happening or how much they could have been paid for it. They didn’t see what it was worth.

So are you for the water transfer or against it? I asked.

Oh, jeez, I don’t know. I just get tired of all the fighting . . .

DEMOCRACY

In August 2003, the Imperial Irrigation District asks the federal government for work files. The government refuses. I can’t help believing in people. The District files a Freedom of Information Act request. The government replies that the cost will be a thousand dollars, which the District immediately pays, at which point the government announces that actually the cost will be five thousand dollars, which the District pays that very same day. Almost three weeks later, the District asks the government where the documents are, and is told they will come in a week. Eight days later, a letter arrives saying the documents will not come for another fifteen days, which is only three business days before the District’s deadline for legal response—in other words, as the District’s lawyers remark,

too late for meaningful review.

Gamely, the lawyers try to present Imperial’s case all the same:

C[oachella] V[alley] W[ater] D[istrict] has an undisputed lower on-farm efficiency than IID and has undisputed access to multiple sources of supply. The determination must address why, under these facts, CVWD as a junior rightholder, should receive a large share of the water ordered by senior rightholder IID. The Determination is totally silent [as to], but must address, why IID should replace all (for CVWD) and some (for M[etropolitan] W[ater] D[istrict of Los Angeles]) of the surplus water these junior right holders used to receive, rather than the junior right holders having to live within their normal-flow year entitlements or obtaining water from available non-Colorado River sources.

The Imperial Irrigation District predicts the results of water reduction: The Salton Sea will die sooner, selenium concentrations in tailwater and leach water will increase in the drains; endangered species such as the desert pupfish will suffer increased pressure in their habitat around Parker Dam. Needless to say, Imperial will enjoy little protection against potentially unlimited liability for environmental mitigation. Her lawyers bitterly quote SWRCB Decision 1600, 1984:

A property right once acquired by the beneficial use of water is not burdened by the obligation of adopting methods of irrigation more expensive than those currently considered reasonably efficient in the locality.

“THEY HATE MY GUTS”

Stella Mendoza was a pretty woman of indeterminate age. She had reddish-blonde hair and dark eyes. We sat around her kitchen table, and she said:

We have this water transfer for seventy-five years. And one of the concerns that I have, is that these farmers like Mike Morgan and the Imperial Group, they want the water allocated to the gate. The way it is now, the IID is a trustee to the landowners, and the landowners have the right to use water as long as they use it reasonably and beneficially. And Mike Morgan wants to dissolve the IID, and have two boards, one for the water, one for the electricity. It’s like the same system they have in Palo Verde. Then the landowners can sell.

I can tell you that of the water we’re entitled to, ninety-eight percent is used for ag purposes, she said proudly. Only two percent is used for urban purposes.

There has to be a water history to the land. There are some lands up in the northern part of the valley where the land is very hard to farm. So the water history for those is not as big as the water history in the Holtville area where they grow a lot of produce.

Why does Mr. Morgan want so much land?

His intent is to control the water. The bottom line is greed and money. If he can somehow get the Board to agree to allocate water to the gate and then the water is allocated to the land, that’s one step in that direction.

Did the split vote reflect a split in the county generally?

The community is kind of fractured. There’s maybe four groups. Right now we have maybe three Board members that are not farmers. And I can understand the mentality of some of the farmers that non-farmers are making decisions that are directed at them: How dare this gal tell them how to use the water? I’m the first woman on the Board and I’m of Mexican descent. What they don’t understand is that IID Board doesn’t only make decisions on the water but also on the power side.

The farmers feel like they’re losing control. There’s maybe five hundred in the valley. So they’re lashing out.

I would think that they’d adore you.

Hell, no. They hate my guts. John Vesey and Mike Morgan, if they could shoot me and put me in a canal and get away with it, they would.

Are more of them on your side or on their side?

It’s hard to tell.—She named one of her supporters and said: He’s one of the farmers who wants to just be left alone, who wants to just farm. And then you have some who don’t feel that way.

Are there farmers who are not water farmers who support the water transfer?

Many. I guess what they’re afraid of, is that the water would just get taken away. But what I tell them is that we’re supposed to be a nation of laws. Laws do stand for something. The law stands that we’re entitled to twenty-three point two million acre-feet of water. If they try to take it away, I’ll see you in court. But they feel that they’re outnumbered. Also, you can be paid for not farming. And that’s very attractive.

I firmly believe in my heart that ag will always pay a major part in Imperial Valley, she continued. As technology improves, I think the farmers will always be more technology-capable, producing higher yields with less fertilizer.

That would mean fewer farms could produce the same amount of crop, I said. And it seems to me that that’s going to mean fewer farms, period.

That’s true, she said. And look at Calexico. They’re going to convert all that farmland into subdivisions. I would prefer Imperial County to remain rural.

What’s your personal feeling about the Salton Sea?

The Salton Sea is a body of water that is evolving, and it’s going through changes.

314

If less water flows into the sea because of this water transfer, well, look, in order to prevent less water flowing into the Salton Sea, the water transfer was amended for additional fallowing. Say, if the water transfer did not go forward, the sea would die anyway. But that is not to say there could be some kind of reparation as with the Dead Sea or the Great Salt Lake. In my mind, they have this North Lake concept. It really sounds good on paper. But where are they going to get this four billion dollars? And my concern is that they’re going to come on back to the IID, and they’re going to tell us that the cheapest, easiest way to save the sea is to fallow more farmland.

Who gets fallowed?

Right now, they’re talking about the cost of an acre-foot is two hundred and fifty-eightdollars. The farmers pay about seventeen. Two hundred will go to the farmer and the rest will go for mitigation. Farmers are already signing up. Greed comes into play.

So most people are going to want more water transfers, right?

Unfortunately. And this transfer, according to our attorney, was never about selling water; it was about protecting our water rights. And that’s bullshit. Because we don’t have an ironclad assurance that Interior won’t come back and hit us again! We’re shouldering all the liability. We’re transferring more water for less money. First they capped our liability at fifteen million, then they came back at fifteen million more, and now it’s thirty-four million. And MWD, they’re good negotiators, they’re not paying a penny for it, and they got off scot free. If we hit a hundred and twenty-two million, if the mitigation goes over that, and we have still more, the state promised us that we would backfill with the money. That’s bullshit. The state doesn’t have the money. I don’t trust them. Andy Horne and myself agree on that. The other Board members trust the state.

She said then: What I don’t understand is that

we have the water,

so we should have had a better negotiating position. And what I think is that we were sold out,

315

and I’m not happy with it. You can write that.

Coachella has always attacked us on our reasonable and beneficial use. They’re junior partners. So they’re always there being jealous. If we lose the right to that water, that means that they get more water. The idea has always been to work as a partner with the rest of the state. But there’s always this envy, this mentality that we’re entitled to too much water.

In the urban communities, over sixty percent of the water is for landscaping! Here, almost all of it is for food and fiber. What we told Interior was, that if you’re going to attack us on reasonable and beneficial use, do it to the urbans, too. But they won’t.

Drearily she said: Unless we have technology, good-paying jobs here in the valley, we’re going to become an industrial community with low-paying jobs, people on relief, on welfare. It’ll probably be a Third World county . . .

316

RIPPLES OF BENEFIT

On the tenth of October, 2003, representatives of the Imperial Irrigation District, the Coachella Valley Water District, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California and of course the San Diego County Water Authority sign the water transfer in Los Angeles. Imperial surrenders two hundred thousand acre-feet a year for seventy-five years; while San Diego also gets seventy-seven thousand acre-feet a year for a hundred and ten years, proffered by Los Angeles; this is for lining the All-American Canal.

317

In short,

the pact will supply San Diego with about a third of its current water needs—as much as 277,000 acre-feet of water each year.

318

That was on Friday. On Sunday an editorial appeared in the

Imperial Valley Press,

decrying an editorial in the

San Diego Union-Tribune

which proposed that the water transfer be considered a “template” for more water transfers.

319

The

Imperial Valley Press

remarked that this statement

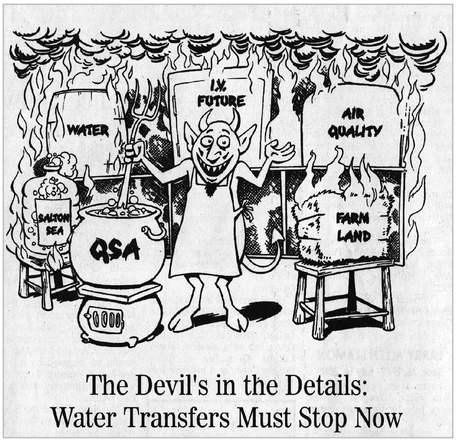

reinforced the idea that “urban interests” have established a beachhead in the Imperial Valley—and their next move will be to construct a siphon . . . Far from being a template for ag-to-urban cooperation and equity, this water study has been a case study in the exercise of raw political power.

What do you think San Diego would have said about that? What would have spewed out of San Diego’s mouth? What would have been the outfall? (Definition of outfall:

the point where sewage is expelled from a system.

) Well, I’ll tell what San Diego did say:

The water transfer agreement provides ripples of benefit across the west.

Chapter 164

YOU MIGHT AS WELL GET OUT OF THE WAY (2006)

T

hey’re building houses in where there used to be farmland, said Kay Brockman Bishop.

I don’t agree with Stella. It’s just like the bollworms coming in. Things change. You learn to roll with the punches and do something else. A lot of the guys, the contract labor, are going to get hurt more than most.

I think it’ll be a suburb before very long. Could be fifty years.

They’re going to do what they’re going to do, and you might as well get out of the way.

But you can walk across the yard and you can hear the wind going whishing past a bird’s wings. You sit someone down on the porch and get ’em a beer or a cup of coffee and say it is sure peaceful here.

... I sat with her, watching the sunset coming and smelling the cool smell of the ditches and then the flies went away, and it got cooler and cooler.

Chapter 165

WATER IS HERE (A VIEW FROM ARIZONA) (1985-2007)

Supplemented by the newly finished All-American Canal and its intake,

the Imperial Dam and desilting works, Imperial Valley can claim the most

secure, cheapest, dependable and abundant water supply in the United

States.

—El Centro Chamber of Commerce, 1939

The unsuspecting traveller who has crossed the Colorado river and entered

Southern California, naturally looks around him for the orange groves of

which he has so often heard and is astonished not to find himself surrounded

by them.

—Mrs. W. H. Ellis, 1912